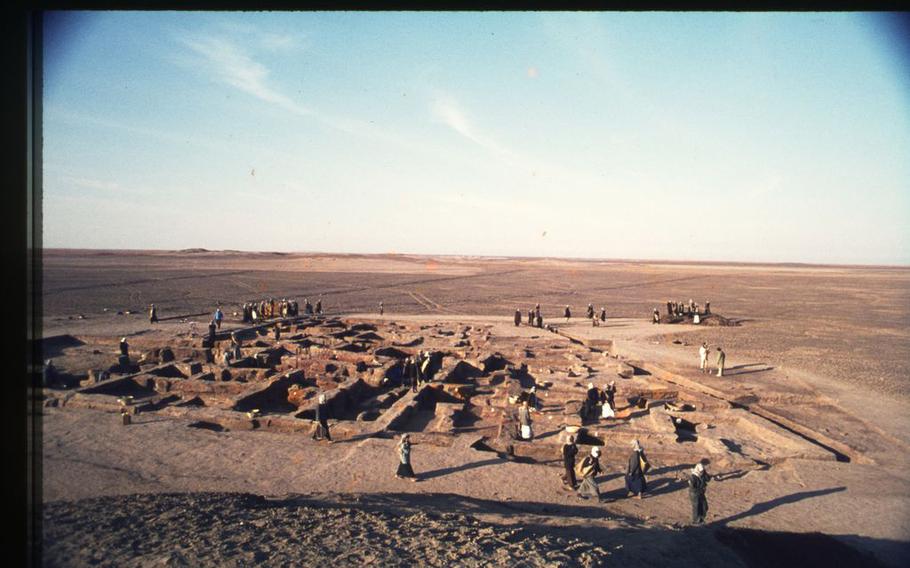

A view of the east end of the complex unearthed by archaeologists in Iraq that could contain the world’s oldest-known tavern. (Lagash Archaeological Project)

You walk into your local bar and order a beer. Your server brings your order, along with a few snacks to nibble on while sipping your brew: Dates and some dried fish.

This was likely the experience for patrons at what might be the world’s oldest-known bar.

Archaeologists recently excavated a site in Iraq dating to around 2,700 B.C. in the ancient Sumerian city-state of Lagash that they think could contain the oldest tavern ever discovered.

“We found the remains of a public eatery, the earliest that we are aware of in one of the first cities of southern Mesopotamia,” said Holly Pittman, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania and project director of the excavation.

An international team of researchers from Penn and the University of Pisa announced the discovery this month. The site was uncovered in the fall at Tell al Hiba, located in southeastern Iraq, about 150 miles from the modern port city of Basra.

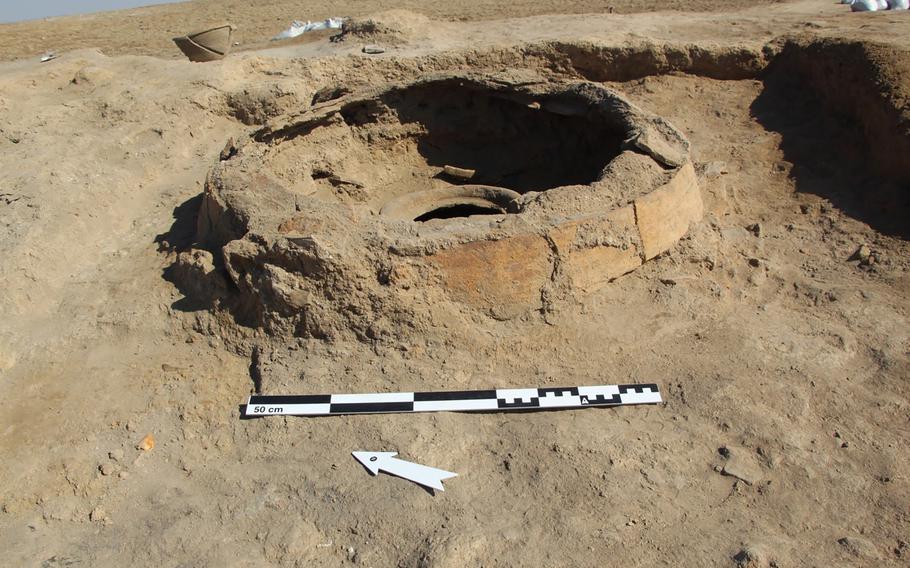

Archaeologists found a seven-room structure featuring an open courtyard with benches and a large open cooking area with a 10-foot-wide mud-brick oven. They also discovered a primitive refrigerator. Known as a “zeer” in Arabic, the device consisted of two bottomless clay jars that used evaporation to help cool perishable items.

The zeer, or ancient refrigerator, found at the excavation site. (Lagash Archaeological Project)

In another room, the team discovered a large quantity of conical bowls that held ready-to-eat food and jars that the archaeologists think contained beer.

“We’re trying to find out now through lipid analysis what was in the bowls or the jars,” said Pittman, who is also Near East curator at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. “But it looks like this was kind of a McDonald’s with prepared food for fast service.”

Lagash was once a bustling community with a thriving commercial district in southern Mesopotamia, known today as the “cradle of civilization.” Located near the confluence of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers, Lagash was one of the oldest cities of the Early Dynastic period, about 2900-2350 B.C.

Some 5,000 years ago, the ancient city was situated on the Persian Gulf, which is about 150 miles away today. According to Pittman, Lagash was a community of an estimated 50,000 people that served as the capital and religious center of a state of the same name. Archaeological digs over the past several decades show that the city was a large manufacturing area for ceramics and other commodities.

Before digging at Tell al Hiba, the Penn and Pisa archaeologists used drone photography, thermal imaging, magnetometry and micro-stratigraphic sampling to see what was under the surface. Using these tools, the team detected evidence of man-made objects a few feet below the site.

“We’ve been working at this particular location since 2019, though excavations have been going on here since the 1970s,” Pittman said. “We used modern systems to get a better idea of where to dig this past fall.”

Pittman said they had detected the remains of a kiln at the site. As archaeologists dug down, they found the eatery just below that.

The 5,000-year-old tavern site uncovered by researchers at Lagash in Iraq. (Lagash Archaeological Project)

“Our field director, Sara Pizzimenti, was really excited when she told me, ‘We have a tavern!’” Pittman recalled. “She trained on Roman tavernas, so she recognized immediately what we had.”

Inside the structure, archaeologists unearthed a myriad items typically found in eating and drinking establishments of the day. In addition to benches and other areas for people to sit, they found at least 20 bowls with food residue and fish bones. Because the dishes were not cleaned, something sudden and dramatic — perhaps a natural disaster — might have occurred at the tavern.

Archaeologists don’t know for certain what was in the numerous jars at the tavern. However, the vast number of clay stoppers with seals featuring government markings — the ancient Sumerians kept track of goods for tax and quality purposes — indicates that some of them at least contained alcoholic beverages.

“We know that beer was the most common beverage for the Sumerians,” Pittman said. “Indeed, during an earlier excavation, a tablet with a recipe for beer-making was found.”

A 1968 dig of a nearby temple by Pittman’s mentor, Donald P. Hansen of New York University, uncovered a structure identified as a brewery, one of the earliest to be found in the region.

Pittman has little doubt that beer was served at the tavern, which could have been similar to a company cafeteria serving employees of the pottery-making industry. And if there was beer, then the waitstaff probably served snacks too.

“I am sure they did,” she said. “Probably dates and dried fish would have been available. I am not aware of any textual descriptions of these foods at the site, but we know ancient Sumerians ate these foods at public gatherings. I wouldn’t be surprised if they were there.”

Safe to say, pretzels were not an option — they wouldn’t be invented for more than 3,000 years.