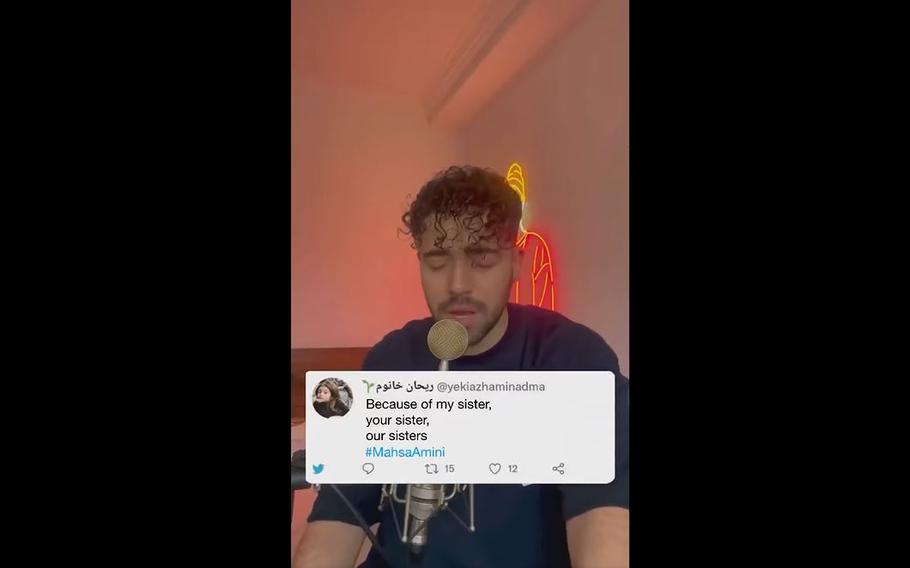

Iranian singer Shervin Hajipour posted the song, “Baraye” — which means “for the sake of” or “because of”— to his Instagram account on Sept. 28. It accrued more than 40 million views, according to Amin Sebati, a London-based expert on Iranian cybersecurity, by the time authorities forced Hajipour to take it down and arrested him the following day. (Facebook)

The unofficial anthem of Iran’s ongoing anti-government protests is a soulful song, with lyrics strung together from tweets by demonstrators risking their lives to defy the country’s ruling clerics.

“Because of dancing in the streets,” the song begins. In Iran, dancing in public is banned.

“Because of every time we were afraid to kiss our lovers.”

“Because of the embarrassment of an empty pocket.”

“Because of yearning for a normal life.”

Other lyrics name corruption, censorship, gender discrimination, environmental degradation and national tragedies, such as the near extinction of the Persian cheetah and the downing of a Ukrainian passenger plane in 2020, in what Iran’s government has said was a military accident.

“Because of women, life, freedom,” the song concludes, echoing a popular protest chant: “Azadi.” Freedom.

Iranian singer Shervin Hajipour posted the song, “Baraye” — which means “for the sake of” or “because of”— to his Instagram account on Sept. 28. It accrued more than 40 million views, according to Amin Sebati, a London-based expert on Iranian cybersecurity, by the time authorities forced Hajipour to take it down and arrested him the following day.

The song, according to Iranians interviewed by The Washington Post, gives voice to sentiments that have driven widespread anger and the largest anti-government protests the country has seen in years, which began with the death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini in police custody in Tehran last month, and which have come to encompass a broad range of frustrations uniting Iranians fed up with grinding poverty, repression, gender segregation and human rights violations.

Hajipour, 25, was released on bail Tuesday, according to Iranian state media. His lawyer did not respond to requests for comment. In an Instagram post after his release, Hajipour thanked his supporters and expressed his love for Iran, vowing not to leave.

By then, “Baraye” had become ubiquitous across Iran and online platforms.

Hajipour’s arrest came as part of a brutal crackdown on the weeks-long protests. Authorities have killed more than 130 protesters, according to rights groups, arrested and injured thousands more, and cut off or slowed internet access across much of the country.

“The song puts decades of depression, hurt and anger into simple words,” said Sarah, a 32-year-old fashion designer in Tehran, who runs her business on Instagram. She would give only her first name, out of concern for her safety.

Sarah said she hears Hajipour’s “lullaby of hope” everywhere: played on mobile phones at protests, blasted from cars, sung by passersby in the streets, shouted from rooftops, chanted at schools and offices and streamed across social media.

“Shervin’s arrest [has] made the song even more popular because the injustice of this action has enraged people,” said Saeed Souzangar, a 34-year-old managing director of a technology company in Tehran. “This song is eternal and the anthem of the revolution, and no matter how much the system tries to stop it from being played, the more you will hear it.”

Souzangar said Monday that he and his colleagues were spending much of their time either protesting — an experience, he said, that felt like “bungee jumping” — or searching for friends in detention.

“My generation didn’t get to live freely in this country,” Souzangar said. “I want future generations to be spared from the psychological and emotional torture we experienced.”

He told The Post on Monday that two friends had just been arrested for “spreading information about the protests,” and he did not know their whereabouts.

Tuesday morning Tehran time, Souzangar said that he had been called in for questioning. He stopped responding to text messages.

“This time, small concessions are not going to work,” he said Monday, referring to chants calling for an end to clerical rule. “Now, all these different groups in Iran have become one, and they have one demand.”

Every wave of political change in Iran has been defined by key songs, slogans and media, said Negar Mottahedeh, a professor of Middle Eastern studies and film and media studies at Duke University. During major protests in 2009, sparked by election fraud, Twitter and hashtags became a key mobilizing tool in Iran and abroad.

Despite the internet crackdown, Hajipour’s song has been able “to move quickly and change people’s hearts and minds,” a significant step even if it does not fundamentally alter the political system, she said.

“Even if these protests die tomorrow, Hajipour’s song will continue to be a form of defiance and heard in every protest to come,” said Holly Dagres, a senior fellow at Atlantic Council, a Washington think tank.

Some of “Baraye’s” lines directly echo chants in the streets.

“Because of my sister, your sister, our sister,” Hajipour sings, alluding to Amini, the woman whose death, in the custody of police who detained her for an alleged violation of Iran’s strict dress code for women, set off the protests.

“For the ruins of poorly built homes,” another lines goes, in reference to the May collapse of a poorly built, 10-story commercial building in Iran’s southwestern Khuzestan province. The catastrophe left the country grief-stricken and fueled weeks of anti-government and anti-corruption protests.

Tina, a 29-year-old from Iran’s Khuzestan province living in Tehran, who would also give only her first name, said one line — “for forced heaven,” strictly enforced Islamic law — resonated the most.

“This one signified all the years of oppression, violence and humiliation us woman have been living with in Iran, forcing us to follow rules that we don’t even believe in,” she said.

Tina said she works at a private company, and that she and her colleagues play “Baraye” several times a day.

In recent weeks, while attending protests she said she has felt an intense feeling of power and unity. But she has been left with a broken heart, she said, because Iran’s leaders are using violence to combat the unrest.

Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, made his first public statements Monday, in which he derided demonstrators as agents of the West and “thugs, robbers and extortionists.” When protests broke out in 2019, sparked by a rise in fuel prices, the government shut the internet down for 12 days. Hundreds, by other estimates, more than one thousand, people died.

“We are defenseless, no one cares about us except ourselves,” Tina said. “Most of the casualties are so young . . . We are fighting this fight alone and with all of our might.”

She said, “Each baraye speaks to the pain and frustration that Iranians have been suffering.”