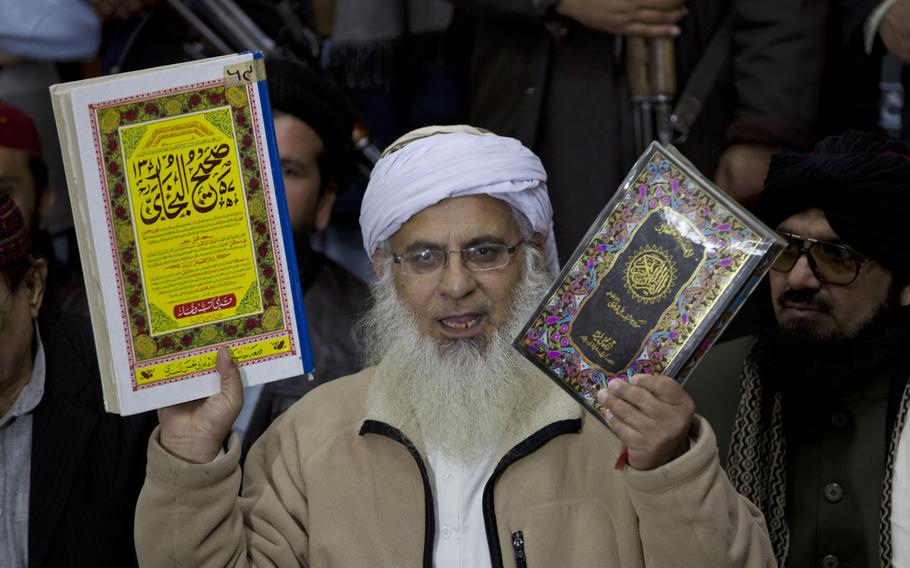

Maulana Abdul Aziz, the Red Mosque cleric and member of the Taliban negotiating team shows religious books in Islamabad, Pakistan, on Feb. 7, 2014. (B.K. Bangash/AP)

ISLAMABAD, Pakistan - For years, the Red Mosque in Pakistan's capital has stood as a bastion of religious defiance, a nerve center of radical Islamist preaching that has drawn thousands of worshipers to hear rabble-rousing sermons by its longtime pro-Taliban leader, Maulana Abdul Aziz.

In 2007, the mosque, also known as the Lal Masjid, and its next-door Islamic seminary, or madrassa, for girls were the site of a bloody siege by Pakistani security forces after a week-long standoff with armed militants inside the compound, which left at least 100 dead. Since then, Aziz has faced numerous criminal charges but has never been convicted.

Now, with the sudden Taliban takeover of Afghanistan, Aziz says his followers' crusade has been vindicated and their moment has arrived.

"The coming of the Taliban was an act of God," the white-bearded cleric, 58, said in a rare interview this week at the girls' madrassa, Jamia Hafsa. He no longer preaches at the mosque, under an agreement he made last year with the government.

"The whole world has seen that they defeated America and its arrogant power," Aziz said. "It will definitely have a positive effect on our struggle to establish Islamic rule in Pakistan, but our success is in the hands of God."

Madrassas in Pakistan have long played a major role in fostering militant Islamic groups, mostly aimed at foreign targets. The Afghan Taliban movement was spawned in a radical madrassa in Pakistan's northwest border region, and Lashkar-e-Taiba, a violent anti-India insurgency, was incubated in madrassas in Punjab province.

But one such homegrown group, known as the Pakistani Taliban, waged war against the Pakistani government for years and is still active in Afghanistan. Officials here fear that the Taliban takeover in Kabul could embolden such extremists to launch a new holy war at home. A surge in religious fervor has sparked violent riots by one group that seeks a crackdown on blaspheming against Islam.

Since last month, Aziz and his followers have periodically raised white Taliban flags on the Jamia Hafsa roof, defying government orders. The third time, on Sept. 18, police cordoned off the area amid growing alarm among nearby residents. Veiled students stood on the roof, shouting taunts.

Police said Aziz threatened them and brandished a gun. He was initially charged with rioting, sedition and other crimes under federal anti-terrorism laws, but the charges were dropped the next day.

"We have resolved the issues through dialogue, to keep the situation in the federal capital normal," Interior Minister Sheikh Rashid Ahmed told a news conference Monday. Of the more than 500 madrassas and 1,000 mosques in Islamabad, he said, "we have an issue with only one."

He said Aziz "comes up with an issue every day, and every day we try to resolve it."

The kid-gloves treatment afforded Aziz stems in large measure from the still-lingering controversy over the 2007 Red Mosque siege, which was ordered by the military government of Gen. Pervez Musharraf after unsuccessful efforts to negotiate with the mosque's leaders.

The assault ignited a national outcry in the majority-Muslim country and sparked a wave of suicide bombings and attacks by the domestic Taliban militants that took years to quell. Aziz, who tried to escape from the besieged compound wearing a burqa, was caught and sent to prison.

He was ultimately acquitted by the Supreme Court on charges of murder and other violent crimes, citing a lack of evidence and failure of witnesses to testify. Over the years, he has faced 27 legal proceedings and spent several stints in prison, but the charges have never stuck.

Meanwhile, the government rebuilt the badly damaged mosque, an imposing redbrick compound located near government ministries, embassies and the headquarters of the national intelligence agency. It has remained a hotbed of extremist fervor, with a new library named after Osama bin Laden, but it has never again violently challenged the government's writ. In return, Pakistani authorities have tolerated its activities, up to a point, in a tacit and strategic peace agreement.

"The Red Mosque operation was and still is a sensitive issue," said a former security official in Islamabad, speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss the matter freely. In recent years, he said, Pakistan has been relatively free of terrorist attacks, and the government wants to keep it that way. "Whenever a problem arises now, the authorities try to settle it peacefully," he said.

At the moment, Pakistan is trying to find a similar balance in its response to the Taliban in Afghanistan. Senior officials have resisted Western pressure to hold the new authorities in Kabul to account for abuses such as beating peaceful protesters, insisting that the more urgent need is to prevent a humanitarian crisis that could spill across Pakistan's border.

In an address Monday at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York, Pakistani Foreign Minister Shah Mahmood Qureshi said it had been a mistake to isolate Afghanistan in the past. According to a statement by the Foreign Ministry, he said the "immediate priority" is to help its suffering people and that a stable government in Kabul would be "more effective at denying space to terrorist groups."

Aziz declined to say what steps he and his followers might take now, only that they will continue the "struggle" to establish Islamic rule in Pakistan. In the past, he has openly called for an "Islamic revolution" against the state. Some see the recent Taliban flag skirmishes as a bargaining chip in the group's relations with the government, as both sides wait to see what happens next in Kabul.

Speaking softly and surrounded by religious books, Aziz blamed Pakistan's problems on selfish greed by the ruling elite, saying its members "live in luxury while the people are starving" and follow misguided Western values of "loving the world more than loving God." He praised the new leaders in Kabul but said they should strive to live "even more simply" in power.

"They should not meet in offices and live in palaces," he said. "They should operate from mosques."

Other Islamist groups here have welcomed the Taliban takeover, as did Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan. But the groups must function within a long-established democracy and a more heterogenous and developed society than Afghanistan. Pakistan has sizable minorities of Christians and Shiite Muslims and a preponderance of moderate Sunni Muslims, although the influence of fundamentalist groups is spreading.

"Most people in Pakistan do not endorse their approach," one Muslim scholar said of Aziz and his associates, speaking on the condition of anonymity to be candid. He said Aziz is "exploiting the moment" as well as his location in the capital. "The government cannot control that group," the scholar said, "but it should ask other like-minded groups to help deal with them."

While Aziz was circumspect in his comments this week, his daughter Tayyiba Ghazi, 30, the vice principal at Jamia Hafsa, proudly described its female students as "religious warriors" in the battle for Islamist values.

Most of the 1,500-plus students are from the same ethnic Pashtun group as the Taliban and come from the northwest region bordering Afghanistan. Girls as young as 5 are sent to live there by poor families who pay no tuition. Many remain through their 20s. Male students are taught at a separate madrassa across the city.

In recent years, older students have acted as moral vigilantes, attacking music stores and kidnapping suspected prostitutes.

"We are all soldiers of Allah," Ghazi said as she showed a reporter around the facility. Sounds of droning recitation came from dimly lit classrooms, where girls of all ages were hunched over low desks with their heads covered, memorizing the Koran.

Ghazi said the staff "teaches our girls to be brave, and they are not scared of anyone, not the police or other forces."

In the recent past, she said, the group has been "balancing its actions" in public to avoid confrontation. But she complained that the government "calls us terrorists and won't let people support us."

"We don't even have a bank account," she said.