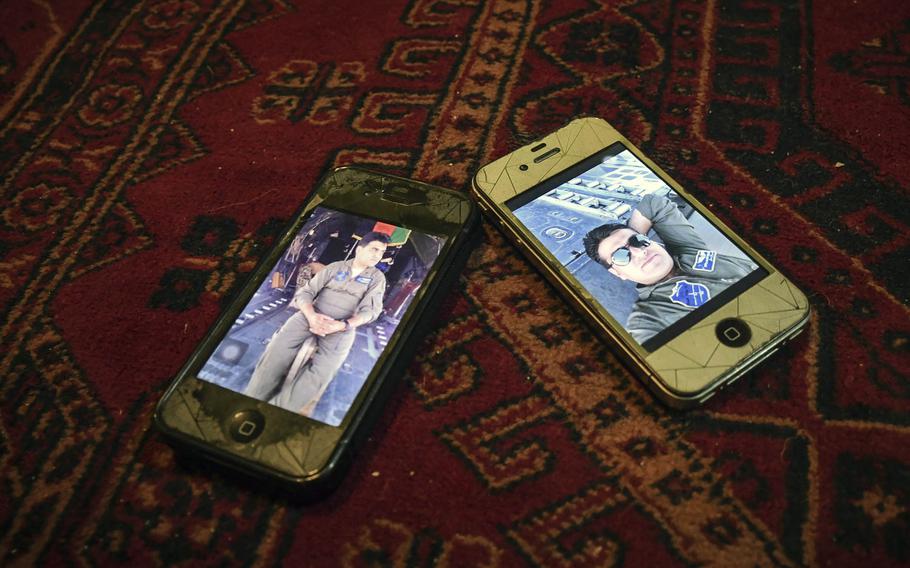

The family of Afghan flight engineer Mahboobulhaq Safi, 30, keep photos of their loved one, who was one of the most highly trained airmen in the Afghan air force and was assassinated on Aug. 27, 2018. The family wants more protection for airmen, who face threats both at work and off duty. (J.P. Lawrence/Stars and Stripes)

KABUL, Afghanistan – The two highly trained Afghan airmen were dead, killed by an assassin who waited for them on their way to work.

Mahboobulhaq Safi, 30 — once Afghanistan’s only C-130 flight engineer — was shot six times Aug. 27, along with Col. Mohammed Shah, 45, one of the country’s few C-130 pilots.

Their families are left asking how Western military forces can justify investing so much money in training Afghan airmen, while not doing more to protect them.

“The government has done nothing for his safety,” said Shah’s brother, Spin Gul, 59, a retired Afghan National Army colonel. “The government should have realized the importance of their job and should have taken measures to secure their employees.”

Strengthening Afghanistan’s airpower is crucial in helping its military fight the Taliban and other militants. The U.S., for example is planning a $11.4 billion modernization campaign to increase Afghan airmen by 20 percent and triple the number of Afghan aircraft by 2023, according to a Defense Department report in June.

Because of their importance in the war effort, Afghan pilots are targeted for assassination and often struggle to keep themselves and their families safe. Threats bring the war from the skies, where Kabul and the West have technological superiority, to the ground, where the Taliban and other militants use guerrilla tactics like ambush and murder.

Niloofar Rahmani, the first female Afghan fixed-wing pilot, told Stars and Stripes how these threats — and what she described as a lack of support from the Kabul government — caused her to leave the Afghan air force and seek asylum in the U.S. in 2016.

“There is so much investment on pilots,” Rahmani, 27, said in a rare interview. “Unfortunately, once they get done with [training] and start their job in AAF, there is no protection or safety for men or women pilots. It is up to the individuals to try to keep themselves and their family alive.”

Spokesmen for the NATO mission in Kabul referred request for comment to the Afghan defense ministries, who said the deaths of Safi and Shah prompted a “serious investigation.”

“Some special measures have been taken for the protection of the rest of employees of AAF,” said Ghafoor Ahmad Jawed, spokesman for the Afghan Defense Ministry, who declined to provide specifics due to security concerns.

A big loss

Safi and Shah were trained under an eight-year, $6.6 billion effort to develop the AAF, which has about 9,000 regular and special operations airmen and now conducts more airstrike sorties in the country than the U.S. Air Force, according to the latest report from the Special Inspector General for the Reconstruction of Afghanistan.

“It is not easy to have good pilots,” Afghan Gen. Abdul Wahab Wardak said. The airmen’s deaths were “a big loss for Afghanistan, because we are currently in a war and losing such pilots affects our activities.”

Shah had been his student, he said, and he “was a very good pilot, he was so professional.” Shah served about 30 years in the Afghan air force. Originally trained under the Russians, Shah could speak four languages, his family said.

Safi for nearly two years was Afghanistan’s only trained flight engineer for C-130s and flew on the first all-Afghan C-130 flight. Working 14-hour days, he sometimes flew 13 missions a week, according to his family and an Afghan journalist who profiled him in 2015.

Their deaths thinned the ranks supporting Afghanistan’s fleet of four C-130s, transport planes that illustrate the progress and continued struggles coalition forces have faced in building up the AAF.

In 2010, the U.S. and its allies began a plan to provide C-130s to the Afghan air force. Flight crews began training on the C-130 in 2013, and the first fully Afghan-led flight flew on June 16, 2014.

But the AAF had only 12 pilots and eight flight engineers trained to fly C-130s as of June, and half of the country’s four C-130s spent months this year in maintenance out of the country, according to a SIGAR report. As the AAF completes more missions, the force has fewer aircraft compared to last year due to maintenance shortfalls, according to a Lead Inspector General report in June.

Maintenance is still performed by foreign contractors, despite the presence of 45 trained Afghan mechanics. The $35 million annual contract for maintaining C-130s requires work to be certified by someone licensed in the U.S., which has slowed the growth of Afghan mechanics, a Pentagon report said.

Why aren’t there more pilots?

The U.S. wants to add 3,000 highly trained Afghan airmen like Safi and Shah over the next four years, but rising insecurity has fed into existing difficulties in training up the AAF.

Training facilities for security forces are often attacked by mortar rounds or have classes canceled due to security concerns, and Taliban gunmen often search for government workers when stopping vehicles. The U.S. is attempting to build an Afghan air force that doesn’t need foreign help, but it is difficult to do in the middle of a war, said retired Air Force Col. Chris Stricklin, former commander of Train Advise Assist Command-Air.

“The mission is not just to train pilots, it is to develop a sustainable and effective air force,” said Stricklin, who was commander during the first Afghan-led C-130 flight.

One “choke point” is a lack of language proficiency, said Stricklin, a board member of the nonprofit Operation Warriors Heart Foundation. Technical manuals require English literacy, and a new plan to consolidate English language training has been hobbled by poor security at AAF training facilities, according to a June Pentagon report on security and stability in Afghanistan.

Insecurity has also contributed to at least 150 Afghans fleeing training while in the U.S. and going absent without leave at 90 times the rate of trainees from other countries, a 2017 SIGAR report said.

This has led to fewer slots being given to Afghan airmen.

Threats and dishonor

Rahmani, who was in the U.S. for training on the C-130 when she filed a claim for asylum, said threats against male and female airmen at their homes affect their ability to fight in the skies.

The U.S. Air Force once touted her as a symbol of progress in developing Afghanistan’s air force. But she has said that threats against her and her family ended her childhood dreams of flight and forced her to flee the country.

“I don’t think any Afghan feels that it is safe in Afghanistan right now,” Rahmani told Stars and Stripes. “If a pilot constantly feels fear for her or his family, it is challenging for them to focus on their mission and be successful. Obviously, they don’t want to lose their family or be killed, that is why AAF is losing their pilots.”

Rahmani enlisted in the Afghan air force when she turned 18, in 2010. She attended advanced flight school to become a C-208 pilot. She flew more than 360 operations and more than 600 flight hours supplying troops across Afghanistan.

The U.S. began to publicize Rahmani, enraging those in Afghanistan who objected to her work as a woman and on behalf of foreign troops.

By 2013, she began receiving death threats over the phone and Taliban night letters on her doorstep. Her brother was almost killed twice, once in a shooting and once in a hit-and-run attempt. Her sister was divorced and forbidden from seeing her child. Some of her uncles and cousins began to believe that attacking her was the only way to restore the family’s honor.

She knew and respected Shah, the pilot, and Safi, the flight engineer. The two airmen were from her old squadron, and Rahmani said she cried when she heard the news. Like Safi and Shah, she always hid her uniform when outside the safety of a base. A member of her family had to escort her to work and back. She carried a gun.

“Serving in every branch of the military, it is very big risk, with no protection, no safety,” she said.

In 2016, while in the U.S. for C-130 training, Rahmani left the Afghan air force and requested asylum in the U.S., citing threats to her safety. Spokesmen for the Afghan defense ministries at the time accused her of lying and said the U.S. should reject her claim. NATO forces criticized her for saying the security situation was “getting worse and worse.”

But she was granted asylum in 2018 after a 16-month wait. Her family remains in Afghanistan.

“I wish my family never would (have) been through all this,” she said. “I loved my career and that was all I could dream for but … I had to alter my dreams in order to protect my family.”

Rahmani said she has not been able to fly since she has gotten to America, but she wants to fly again and join the U.S. Air Force.

Families left behind

In Kabul, the family of the two slain Afghan airmen called for better protection of pilots by the Kabul government as they showed reporters the spot where their loved ones died.

The two men lived in the same neighborhood in north Kabul and would take a taxi to work together. Shah lived in a rented apartment, and Safi lived with his family. Their loved ones asked why the two airmen did not have access to a secure facility or barracks like the ones planned for female pilots.

About 6 a.m. Aug. 27, Shah and Safi arrived at the meeting point for their taxi, at an alley near a graveyard. Shah always tried to get to work 30 minutes early, and Safi was looking forward to a flight to Kandahar. The two always hid their uniforms as they walked and always varied their routes, and their families said no one held any personal grudges against the two men.

Habibulhaq Safi, the brother of Safi, pointed out a corner in the alley where the gunman waited for them. The government tried to clean the pavement, but the blood has stained the concrete, said Safi, who had to pick up his brother’s body. The gunman shot his brother and sped off with someone waiting on a motorcycle, he said. No group has claimed the killings.

The families don’t want other Afghan airmen to suffer the fate of their loved ones.

“I think the government should have put a serious attention to the security of their air force personnel,” Safi’s father, Azizulhaq, 58, said. “My son is gone now, but those who are alive should live in a very secure residency, and the government should provide them with [that].”

A few blocks away, the family of Shah gathered around a shrine with his picture. The pain of losing his brother will always be with him, said Spin Gul, the retired colonel. His brother truly loved his country, he said. Gul pointed to a stack of diplomas and certificates his brother had earned while learning to fly under the Russians and the Americans.

“My brother always loved learning. He got all of these diplomas. And what did they do for him?” Gul asked. “He is dead now.”