Europe

As the fight moves far beyond the front, Ukraine devises drone hunters

Bloomberg June 2, 2025

A technician prepares a Shrike drone at the Skyfall military technology company in Ukraine. (Andrew Kravchenko/Bloomberg)

A battle is shaping up in the skies over Ukraine and Russia, as the ingenuity of drone engineers on both sides opens up new opportunities and threats far behind the front lines.

This was on full display on Sunday when Ukraine launched a dramatic series of strikes deep in Russian territory, damaging a significant portion of the Kremlin’s strategic bomber fleet. Around the same time, Russia unleashed one of the biggest drone and missile attacks against Kyiv.

The escalation has touched off a new round of innovations: Ukraine is now developing a generation of drones designed to identify and shoot down other unmanned aerial vehicles. The goal is to target Iranian-designed Shahed drones, which have a triangular frame and are mass produced in Russia.

Oleksandr Kamyshyn, an adviser to Ukraine’s minister of strategic industries, said in a recent interview Ukraine is scaling up production of weapons that have had success shooting down the Shahed-style drones around Kyiv and the surrounding region.

The issue has taken on added urgency as Russian barrages grow in ferocity ahead of peace talks this week in Istanbul. In May, Russia demonstrated it can launch hundreds of Shaheds on a regular basis, signaling its growing capacity.

The escalating drone attacks have stretched Ukrainian air defense systems thin and led to a higher number of civilian deaths since U.S. President Donald Trump began pressing for an end to fighting in February with calls to the leaders of Russia and Ukraine.

The proliferation of cheap drone technology in recent years has radically altered battlefields, with traditionally powerful militaries often on the losing end. The low-cost weapons can take out equipment with much higher price tags, including tanks, ships and even other more valuable drones.

This trend was highlighted by the operation on Sunday that struck four Russian airbases, including one in eastern Siberia. The attacks damaged about a third of Russia’s strategic bombing fleet, according to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy. Ukraine assessed the damage to be at least $2 billion, according to a Security Service official who asked not to be identified as the details are not public.

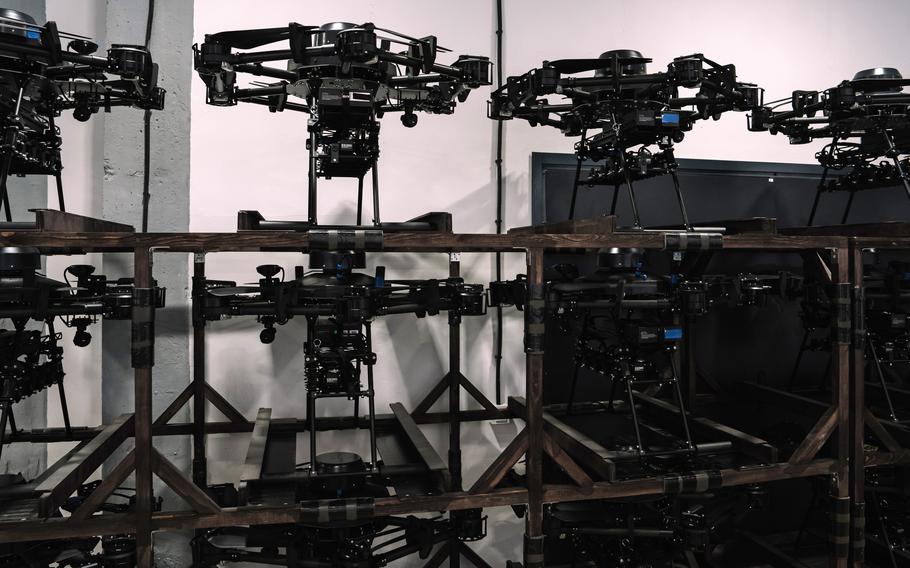

Ukrainian Vampire hexacopter bomber drones at the Skyfall military technology company. (Andrew Kravchenko/Bloomberg)

A similar dynamic was at play in Yemen, one of the poorest countries in the world, where Houthis successfully targeted U.S. surveillance drones with surface-to-air missiles. Houthi militants shot down at least seven Reaper drones, each costing about $30 million, in a six-week period during the U.S. bombing campaign, the AP reported in April. Trump soon after ordered a halt to the campaign and announced a ceasefire with the group.

Defending against drone attacks is historically expensive. Israel, which has the world’s most successful battle-tested air defense system, relies mainly on pricey missiles to shoot down threats. In May, the Israeli Defense Ministry acknowledged that it deployed laser weapons during its ongoing war to stop “scores” of aerial attacks, including from drones. Laser systems, like interceptor drones, have much lower operational costs.

Three domestic producers make Shahed hunters that cost around $5,000 each, according to Kamyshyn, the industry minister’s adviser. Executives interviewed for this article said some interceptors under development can cost as little as $300 a piece.

The strategies they use and their degree of autonomy varies. Some seek to explode near an enemy drone to knock it down, while others fly like a bullet and need to score a direct hit.

What they have in common is they are relatively cheap. Shaheds, estimated to cost about $35,000, are Russia’s preferred one-way attack drones, according to the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Origin Robotics, a Latvia-based drone maker, is among the many companies seeking to counter Shaheds. Origin will send test drones to Ukraine in June that explode in the vicinity of incoming UAVs to take them out.

“Once it gets close enough to a target, a warhead detonates and the target is hit with fragmentation,” Origin Chief Executive Officer Agris Kipurs said in an interview at a drone conference in Riga last week. “It is exactly used for that type of a target: large armed loitering munitions.”

While the economic calculus is in Ukraine’s favor, drones aren’t successful enough yet to replace other air defense systems, according to Bloomberg Intelligence analyst Wayne Sanders.

The idea to build drone interceptors has found support at the highest level of Ukrainian leadership. Zelenskyy discussed Russia’s battlefield tactics and increasing aerial barrages with his war council last week, and ordered his top military commanders and intelligence chiefs to investigate countermeasures.

“We have jets now to shoot down drones,” Zelenskyy said, adding that they faced a problem with the Shahed attacks. “We are also moving in the direction of drone-drone interceptors.”

Zelenskyy is also pushing allies for $30 billion by year’s end to boost domestic weapons production.

Drone hunters have other limitations, too. They can’t defend against Russia’s more capable missile systems, which are faster and carry more firepower than Shaheds. U.S.-made Patriot missiles, which cost between $3 million and $6 million each, are the most effective way to target those weapons.

“The dependence on the U.S. has been evident both in direct and indirect ways,” Sanders said. “Direct funding of weapons capabilities, as well as indirect investments into Ukrainian manufacturing capabilities so that they could stand up their own industries.”

Currently, the alternative to interceptor drones is often soldiers with truck-mounted machine guns, a low-tech solution with a poor success rate that gets worse when their targets fly at higher altitudes. Kyiv also uses its small fleet of F-16 fighters, donated from NATO allies, to shoot down drones. Ukraine has faced more than 20,000 long-distance drone attacks in the three-plus years of fighting.

Russian technology isn’t standing still either, according to Carl Larson, executive director of Defense Tech for Ukraine, an international group of volunteers providing equipment to Ukraine.

Russian fixed-wing drones are now often equipped with rear-facing cameras and programmed to take evasive maneuvers if they spot a drone trying to intercept it, Larson said in an interview. “It’s immensely wasteful, inefficient and frankly difficult to physically hit a drone with another drone,” he said.

Ukraine is developing fixed-wing drones that smash into Russian ones, as well as other drones that carry recoilless shotguns to shoot down enemy aircraft, Larson said.

Skyfall, which is one of Ukraine’s biggest drone producers, is tweaking its popular first person view model to intercept UAVs, according to a company spokesperson who asked not to be identified due to security concerns.

FPV drones, like the ones used to target Russia’s strategic bombers, have become an essential weapon for both sides in the war. They can travel at speeds of as much as 100 miles an hour with small explosive charges.

Such drones have already caused a radical rethinking of how the front is organized, forcing soldiers to avoid concentrating in groups and pushing vehicles and other equipment much further behind the trenches to avoid getting hit.

As FPVs are increasingly used to target other flying objects, they could change the skies as well.

A Shrike drone during testing in Ukraine. (Andrew Kravchenko/Bloomberg)

The drone-hunting version of Skyfall’s Shrike FPV costs between $300 and $500, depending on the configuration, and can target reconnaissance and strike drones, the spokesperson said.

In April, Ukraine’s 63rd brigade operating along the front in the east of the country published a video that appeared to be Shrikes targeting a Supercam UAV and a Merlin, which is one of Russia’s most sophisticated reconnaissance drones. The video couldn’t be independently confirmed.

The spokesperson said Shrikes can’t target Shaheds, which travel at much higher altitudes.

“We’re focused on interdicting the FPV suicide drones and the bomber drones,” Defense Tech for Ukraine’s Larson said. While Europe and the U.S. are good at building “fancy and expensive systems,” Ukraine needs its own low-cost, scalable solutions to counter the Russian attacks, he said.

With assistance from Christina Kyriasoglou and Aaron Eglitis.

©2025 Bloomberg L.P.