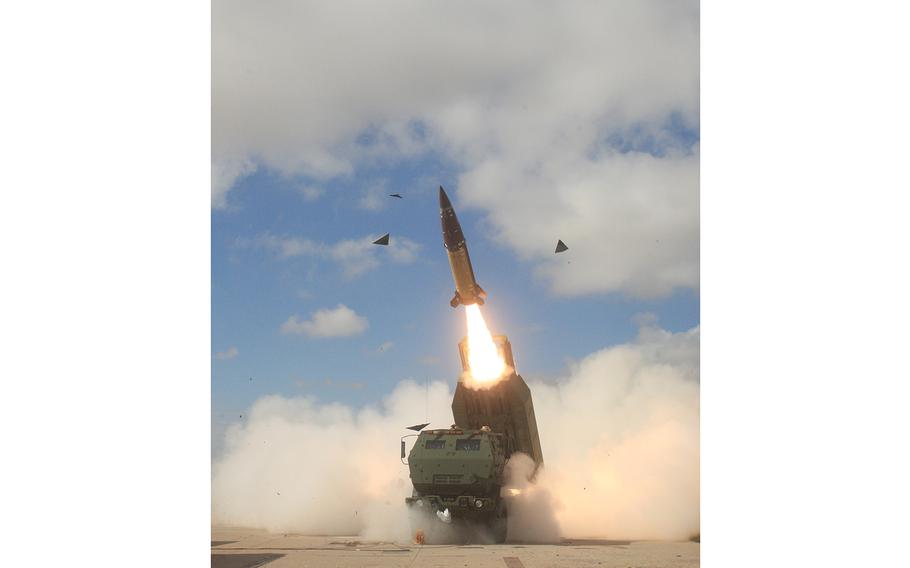

An Army Tactical Missile System is fired at White Sands Missile Range, N.M., on July 10, 2015. (Katie Grandori/U.S. Army)

Following Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky’s visit to Washington on Thursday, the Biden administration is moving toward providing Ukraine with ATACMS - long-range missiles long sought by Kyiv.

Several people familiar with the ongoing deliberations told The Washington Post that the administration is nearing an announcement on the decision and that the United States would deliver a version of the missile that scatters cluster bomblets. The provision of cluster weapons is already a subject of controversy after the United States began sending them to Ukraine in July.

Washington has been reluctant to provide ATACMS, in part over concerns about their maximum range - which could reach well into Russia. The move would represent the latest in a pattern of U.S. decisions throughout the conflict: agreements to provide Ukraine with increasingly complex or powerful weapons, previously held back over concerns including the possibility of escalation with Russia.

()

Here’s what to know about ATACMS, the Army Tactical Missile Systems with which the United States is on the cusp of arming Ukraine..

What are ATACMS missiles?

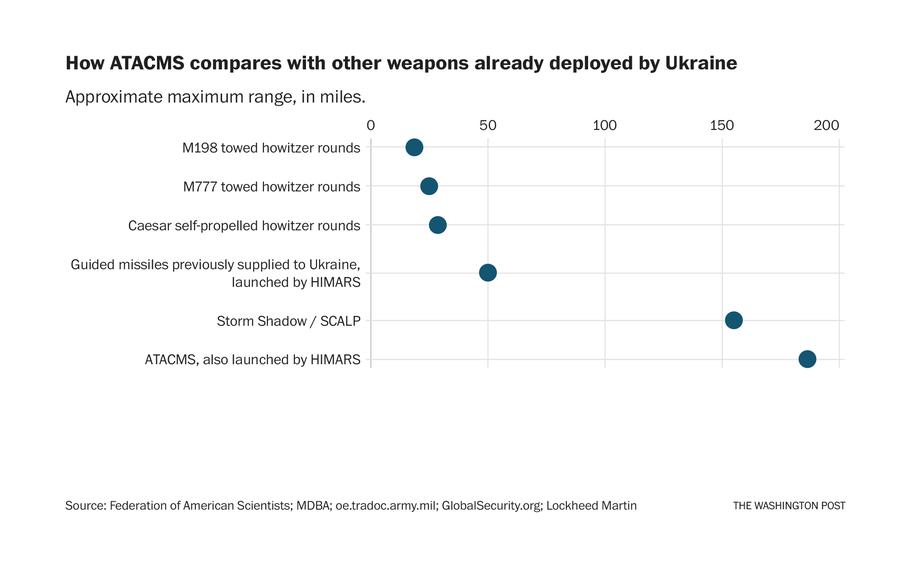

ATACMS, depending on what version the United States agrees to send, could have a maximum range of 190 miles, more than double that of Ukraine’s Soviet-era Tochka-U missile.

Lockheed Martin, the ATACMS manufacturer, makes 500 units of the system a year, but their sale is designated for countries other than Ukraine.

Britain and France have provided Ukraine with cruise missiles, launched from planes, with a range of about 140 miles. ATACMS are launched from the ground.

The ATACMS cluster version disperses hundreds of individual bomblets over an area. Cluster munitions, which are banned in much of the world, have come under criticism by human rights groups, who argue that they are potentially indiscriminate and can leave behind unexploded remnants likely to harm civilians.

Why has the U.S. avoided sending ATACMS to Ukraine, and what has changed?

The Pentagon has resisted supplying Ukraine with ATACMS, concerned that the missiles could land in Russia - a worry that Ukrainian officials have described as paternalistic. Washington’s refusal stems from fears that supplying the weapons - which Moscow has already said would cross a red line - would escalate the conflict and lead to a U.S.-Russia confrontation.

The United States has a fixed stockpile of ATACMS. Sending some to Ukraine would reduce the U.S. stockpile without quick replacement. The Pentagon had also said Kyiv had more pressing needs than ATACMS. The cluster variant, as opposed to the single or “unitary” warhead version, is comparatively abundant in U.S. stockpiles but no longer favored - which could make it a more attractive option to send to Ukraine. Consideration of the cluster warhead ATACMS was first reported by Reuters.

In May 2022, President Biden told reporters that Washington is not “going to send to Ukraine rocket systems that can strike into Russia.” A year later, in late May 2023, Biden budged, saying for the first time that the provision of ATACMS was “still in play.”

This week’s shift comes as Ukraine’s counteroffensive, launched in June, makes inching progress against Russia’s defenses in the southeast of Ukraine.

What are HIMARS?

ATACMS can be launched from HIMARS - High Mobility Artillery Rocket Systems - which the United States has been sending to Ukraine since last year. So far, the United States has provided guided missiles for the system with a 50-mile range.

Ukraine praised HIMARS as a “game changer.” Light at mobile, it has granted Ukrainian forces mobility on the battlefield.

The M142 High Mobility Artillery Rocket System, by far the most advanced system provided by Washington to Kyiv, is light and wheel-mounted, granting its operators more agility on the battlefield.

The system posed such a threat to Moscow’s operations that Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu ordered commanders to prioritize targeting and destroying it.

Karen DeYoung and John Hudson contributed to this report.