Europe

Neither snow, nor sleet, nor war: Ukraine mail carriers carry on

The Washington Post August 19, 2022

Postal workers sorting packages at a facility in Mykolaiv on July 15. Despite the war, Ukraine’s postal service is still delivering mail. (Wojciech Grzedzinski for The Washington Post)

MYKOLAIV, Ukraine - First came the boom. Then the air raid siren.

"Turn off the machines! Turn off the machines!" yelled a mail sorter.

Moments before, workers in this southern Ukrainian city at the regional headquarters of Ukraine's national postal service, Ukrposhta, had been absorbed in their early-morning shift: taking packages of varying shapes and sizes from a conveyor belt and distributing them according to their final destinations.

Now, they scrambled to safety as the sound of the explosions grew louder. "It's coming closer and closer!" yelled an employee, huddled in an entranceway with a group of colleagues.

Forty-five minutes later, the all-clear was given. Slightly behind schedule - time they would make up in short order - the sorting facility's roughly 45 employees returned to work.

Since the beginning of the war with Russia, Ukraine's postal service and privately owned courier companies have continued to make deliveries and carry out financial services, such as transferring money and paying pensions, even during the height of the fighting in places like Chernihiv, Sumy, Kharkiv and the capital, Kyiv.

Their job is not high-profile, but still crucial to the functioning of Ukrainian society during wartime - one that takes the unofficial motto of the U.S. Postal Service ("Neither snow, nor rain, nor heat, nor gloom of night . . .") to another level.

Workers sort mail at a postal warehouse. (Wojciech Grzedzinski for The Washington Post)

The blasts last month were the result of Russian missiles striking two universities in the center of town, about five miles from the postal facility. The attack was part of an intensification of Moscow's airstrikes in the region.

The postal workers' alarm was understandable. Their workplace is in an industrial district on the eastern edge of the city. Russian forces frequently concentrate artillery strikes on a nearby rail yard and military airport. In early July, a tank shell smashed into the back of one of the postal headquarters' buildings and shattered the windows.

Officials at Ukrposhta say that of its approximately 73,000 employees, 15 have been killed and 14 injured during the fighting. About 50 post offices have been destroyed, while 480 have been damaged, some repeatedly.

Even so, Ukrposhta had continued to work until recently in some of the regions occupied by Russian forces. Its general director, Igor Smelyansky, announced on his Telegram channel on Aug. 1 that the company was ceasing operations in the occupied portion of Zaporizhzhia, the last Russian-controlled region where it was functioning.

Smelyansky wrote that this was necessary because of "a significant threat to the lives of workers" and because of robbery by Russian soldiers, who were "a collection of thugs and a gang of beggars."

He ended his Telegram post with two messages to Russian forces occupying Ukrainian territory, lifted from Arnold Schwarzenegger's Terminator films: "Hasta la vista, baby" and "Will be back" - with a photoshopped image of Schwarzenegger in front of a Ukrposhta office.

He was continuing a Ukrainian postal service tradition of trolling the Kremlin. One of its most popular wartime products, which quickly sold out, was a stamp with a drawing of a Ukrainian soldier making an obscene gesture to a Russian military vessel - a reference to the defiant response of Ukrainian soldiers to a Russian ship near Snake Island at the beginning of the war.

When the Russian army swept into the country at the end of February, Ukrposhta workers were among the first to spot the invading forces.

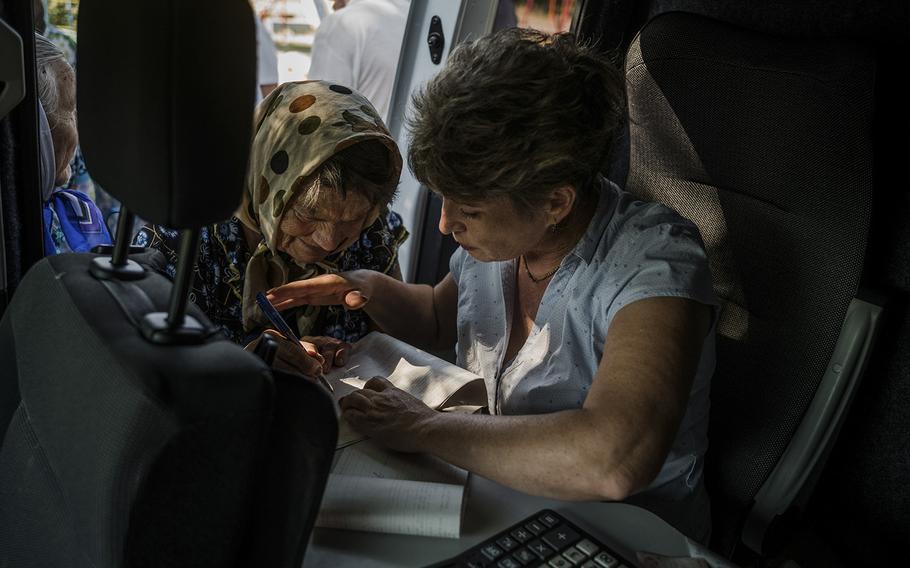

Postal worker Alona Osukhovska helps a woman sign for her pension check. (Wojciech Grzedzinski for The Washington Post)

Olena Doroshenko, Ukrposhta director in the northern region of Chernihiv, said she found out at 5 a.m. that hostilities had begun - before any news reports or public announcements - from a postal worker near the Russian border.

"We have Ukrposhta employees in every population center and so they saw the tanks coming through," Doroshenko said by telephone. "The head of the branch in Novhorod-Siverskyi called me and said, 'Olena Mykolaivna, war has begun!' "

As fighting raged in the Chernihiv region through March, Doroshenko spent much of her time huddled in a basement in her village of Brusyliv, which was occupied by Russian forces. Still, she managed to connect with her workers and direct the postal operations. "We didn't miss a day of work," she said.

Mail and packages couldn't be delivered over front lines, but Doroshenko and her employees set up a system of money transfers so that pensions could be paid.

"We just had to invent and find nonstandard ways to have cash in these branches," she said. "So, we used the Telegram channel and WhatsApp, and I called the community heads and said quietly, 'Let's transfer the money to the bank accounts of businesspeople and businesses.' And they brought money to the post office, and with that money we at least partially paid out pensions."

At times, Doroshenko said, Ukrainian partisan forces helped carry bags of money into occupied areas, traveling through forests and crossing rivers. After Russian forces withdrew, she returned to work in Chernihiv city on April 1.

Many of her workers had fled the region, however. "I simply took my car and a mailman, and I myself serviced the villages because we didn't have enough people and means of transport."

With Russian forces bearing down on his city in late February, Yehor Kosorukov, head of the postal service in the Mikolayiv region, sprang into action delivering parcels and pensions. Working from his fourth-floor office overlooking the front line, Kosorukov now manages an operation focused mainly on distributing pensions by mail to the elderly and disabled who have stayed behind.

"Leaving isn't an option. My family has asked me to leave. I tell them I can't. This is my country and I have a job to do," said Kosorukov. "A captain always goes down with his ship."

Postal workers bring pension checks, letters and packages to a village in the Mykolaiv region on July 15., 2022. (Wojciech Grzedzinski for The Washington Post)

Before the war, about 60% of the parcel delivery market was handled by Nova Poshta - or "New Post," a Ukrainian-owned courier company. Yevhen Tafiichuk, the firm's chief operating officer, said that when hostilities broke out, "we understood that if we stop working, it'd be the collapse of the country." So the company's leadership decided to "work until the very end."

When Russia invaded, deliveries immediately plummeted from more than 1 million a day to just over 30,000. But through March, these numbers started to climb. The company began to deliver to hot spots like Kyiv, which was partially surrounded by Russian troops, and Kharkiv in the east, which was under constant bombardment.

Nova Poshta's top management set up its own war room, monitoring information around-the-clock and altering its delivery routes and stores' opening hours to minimize the risk to its employees. One Nova Poshta worker died on the job, Tafiichuk said, although 27 have died outside of work and fighting on the front line.

"We met three times a day," Tafiichuk said. "There was a map of which branches were captured, which ones weren't captured, from where [the Russians] were attacking. You know, it was more like something military."

Borys Tkachukovsky, a Nova Poshta manager, opted to work as a courier in Kyiv during the worst weeks of the fighting, transporting humanitarian aid, food and military items such as uniforms and flak jackets.

"Each of us is a soldier," he said. "The military needs a strong rear support - it needs to be dressed and fed. We don't take guns in our hands. Our parcels are our guns."

In the areas close to the front line in the Mykolaiv region, mail carriers with the national postal service travel in armored vehicles to designated meeting spots.

On a sunny day late last month, at a location on the outskirts of the city of Mykolaiv, residents were already jostling one another in a line that had formed. The back of the truck swung open, and they approached one by one to receive packages, cash their pensions and pay utility bills.

Ivan Setianov, 56, walked up to the truck with his yellow Labrador, Maggie. "I'm waiting on a fertilizer for my garden," he said. "It's supposed to be here by now, but with all the shelling, I knew there would be delays."

"Do you have a package for me?" he asked the mail carriers.

___

The Washington Post's Anastacia Galouchka contributed to this report.