KNU fighters from Brigade 7 move through a jungle after returning from the front line in Myanmar. (For The Washington Post)

SOUTHEASTERN MYANMAR — For decades, Myanmar’s ethnic minorities have rebelled against the country’s military, but mostly on their own and with little success.

Now, however, nearly three years after a military coup ousted Myanmar’s democratic government and triggered a civil war, it’s these ethnic rebels, camped out in the country’s mountains and jungles, who pose the biggest potential threat to the ruling junta.

While Western governments and international aid agencies have focused much of their attention on the pro-democracy forces led by exiled members of the ousted civilian government, it is increasingly the ethnic rebels tenuously allied with them who are shaping the trajectory of the conflict, security analysts say. These groups have troops, guns and grenades. They control territory, collect taxes and run schools and hospitals. Just in recent weeks, they’ve notched battlefield victories that security analysts say have pushed the junta into its weakest position since the coup.

On a recent morning, Washington Post journalists motored down a mud-colored river on a long-tail boat for a rare visit to the undisclosed headquarters of the country’s oldest and one of its most powerful ethnic armed groups: the Karen National Union, or KNU.

Beyond a river bank and past a curtain of trees, several hundred soldiers from one of the KNU’s seven brigades surrounded a clearing that functioned as their base. Some stood on trucks with AK-47s slung across their chests; others squatted on the ground next to grenade launchers and shoulder-fired rockets. In the center, at a long table, sat a bespectacled 64-year-old rebel leader cracking open a fistful of betel nuts.

“We are doing this revolution to get peace,” said P’doh Saw Thaw Thi Bwe, the joint secretary general of the KNU. “But not just for our territory. For everyone.”

In exclusive interviews, Thaw Thi Bwe and other KNU leaders described the group’s armed campaign and its growing efforts to strike alliances with other ethnic rebels and resistance groups.

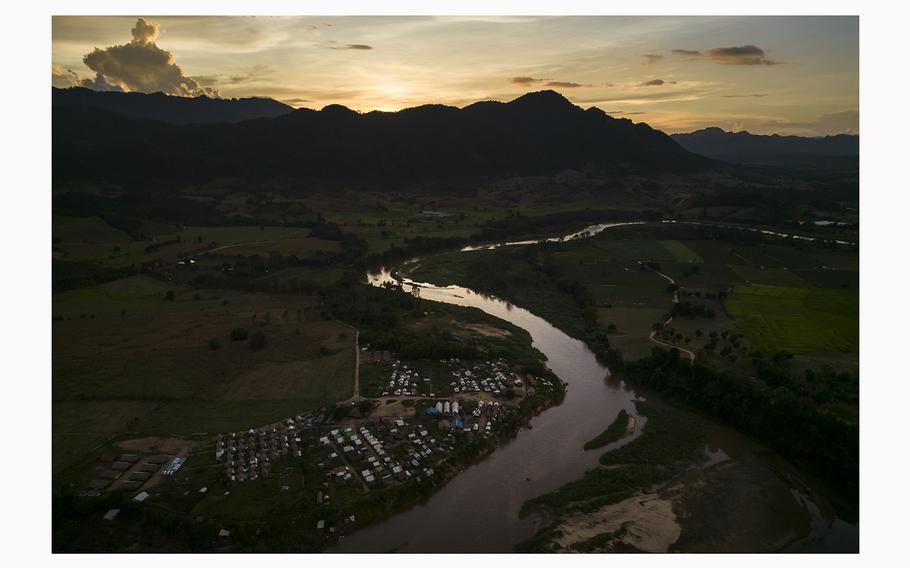

A lush mountain range of Karen-held territory in Kayin State, Myanmar, is seen across the Moei River, which runs along the Thailand-Myanmar border. (For The Washington Post)

The KNU, which has been fighting the military on behalf of ethnic Karen people for 74 years, was the first of several rebel groups to oppose the 2021 coup. Within months of the military’s takeover, it voided a previous cease-fire agreement and resumed attacks on military positions across southeast Myanmar. KNU leaders say they have also armed and trained thousands of insurgents from other ethnic groups, including the Bamar ethnic majority, which has traditionally supported the military. (The Bamar lent their name to Burma, the previous name for Myanmar.)

The decisive role of ethnic insurgents in the conflict has come into sharp relief in recent weeks after an alliance of several other rebel groups launched a surprise offensive in Myanmar’s northern Shan state, forcing the military to publicly cede control over major townships. In the south, Karen rebels and their allies, the Karenni, launched simultaneous attacks on military bases, while in the west, a militia representing ethnic Rakhine people opened a new front in the war against the military.

The synchronized attacks, which analysts call unprecedented, are still unfolding. But the escalation has made clear that Myanmar’s ethnic rebels are no longer a peripheral factor, according to Min Zin, who runs the Myanmar-based Institute of Policy Studies - Myanmar. “They’re kingmakers,” he said.

New fighters, new alliances

Since the coup, the KNU’s armed wing, known as the Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA), has grown to more than 10,000 troops, according to the army’s adjutant general Hsa Tu Gaw, who oversees personnel. Each of its brigades has added several hundred recruits, and there are entirely new militias, loosely organized under what is called the People’s Defense Forces, that are also under KNLA command in southeast Myanmar, he said.

Some of these new fighters are Karen. But many are not. “These young people feel like they have no other choice but to hold up a gun and fight,” said Hsa Tu Gaw. “For the revolution, this is good.”

Nwe Nwe Wyin, who is Bamar, was a college student in the city of Mandalay when she saw another student fatally shot in the head by security forces during peaceful anti-coup protests in early 2021. Within weeks, she said, she had dropped out of school and was making her way to Karen-held territory.

“People were being killed,” said Nwe Nwe Wyin, now 23, her hair cropped close to her ears as a soldier for the KNLA. “I had to find another way to resist.”

Fighters of Brigade 7 of the Karen National Liberation Army rest on the back of a pickup truck after returning from the front line in KNU headquarters in October. (For The Washington Post)

The KNU’s armed wing has deployed many of these new rebels in a campaign to push westward and southward from its territory, aiming to cut off key trade routes to Thailand and to sever the military’s main link between the capital Naypyidaw and the country’s largest city, Yangon.

The group has also, however, sent a steady flow of fighters back to their hometowns in the Bamar heartland, helping to transform what used to be military strongholds into areas of fierce combat, security analysts said.

This combination of newer, pro-democracy insurgents and older, battle-hardened rebels has not occurred on this scale before in Myanmar and it has posed a potent challenge to the military. In the heavily contested regions of Sagaing and Magway, analysts said, the most successful insurgents have been trained by ethnic rebel groups.

Spared so far

The military did not respond to requests for comment for this article. But at a news conference in August, junta spokesman Zaw Min Tun said he was “amazed” by the growing collaboration between ethnic rebels and “terrorist” insurgents and that it could place the “entire country in jeopardy.”

According to conflict-monitoring groups, the military has carried out hundreds of airstrikes on KNU territory, which stretches across a jungle area roughly the size of Maryland. The raids have spared the group’s headquarters so far, though in the last 10 months, airstrikes have hit the command centers of two of the KNU’s closest allies, the Chin and the Kachin ethnic rebel groups.

“We know they will attack us,” said Saw De Kwe, a brigadier stationed at a KNLA base tucked at the bottom of mist-covered hills. “We just don’t know when.”

It’s not just bases at risk. After the coup, teachers, doctors, bus drivers and other government workers who refused to work for the junta arrived here in droves.

A hospital that had been languishing for two years without qualified doctors became fully staffed with about 30 former employees from government medical centers, said Saw Diamond Khin, the KNU’s head of health services. The facility, which treats both civilians and soldiers, is now the most advanced in KNU history, he said.

There are six doctors, including an orthopedic surgeon, an anesthetist and a pathologist. It has two operating rooms, an X-ray machine, ultrasound equipment and a laboratory. And on one end of the teal-colored building, two large bunkers have been dug into the ground.

Medical personnel work at a hospital in Karen-held territory. (For The Washington Post)

The hospital has been kept secret except to local villagers and is surrounded by checkpoints staffed by KNLA soldiers. Still, Diamond Khin said, if the military found it, “it would take them just minutes to destroy it all.”

Generations of rebellion

As dusk descended, Thaw Thi Bwe, the KNU joint secretary general, thwacked at overgrowth in front of a cemetery where Karen soldiers were buried. Many of them didn’t die in combat, he said. They died of sickness or of old age, waiting for the end to a revolution that never came.

“I know every single one,” he said, walking by rows of stained wooden crosses. “Can you believe it?”

Many KNU leaders, like him, joined the insurgency as young men and now have children, even grandchildren serving on the same front lines. Even as they boasted about recent gains, many had been at war too long to presume victory would be easy.

The cost of ammunition has tripled since the coup, and there are about 600,000 or so people displaced by fighting now living in KNU territory who need food and shelter, leaders said. A breakaway militia has drawn away some donations from overseas Karen communities. And several KNU leaders have struggled to shake allegations of corruption, spurring disillusionment in some corners of the community.

Perhaps the biggest challenge, however, lies in navigating the shifting alliances and rivalries within the resistance movement, KNU leaders said.

Myanmar’s democratic government in exile, known as the National Unity Government, says it leads a united front against the military. But many rebel leaders are still skeptical of NUG leaders, alleging that many are former government officials who stood by in previous decades as the military brutalized ethnic minorities. The NUG says it supports a federal democracy, but it’s unclear how much power it would share with ethnic leaders, said P’doh Kwe Htoo Win, chairman of the KNU.

“Bamar people think they own the country,” he said. But people like Nwe Nwe Wyin, the former student from Mandalay, made him think things could be changing, he added.

After her basic training two years ago, she was placed in a unit assigned to protect the KNU command center. Sitting in a wooden shack near her spare quarters, she talked about the people in her brigade, Karen and Bamar, who had just returned from fighting alongside other ethnic rebels in a neighboring state. Their boots and rifles were muddy, their eyes reddened at the corners.

Nwe Nwe Wyin missed Mandalay, but she wanted to go where they’d been. She wanted to do what she came to rebel territory for, she said, which was to fight.

Yan Naing in Bangkok and Cape Diamond in Yangon contributed to this report.