Asia-Pacific

In G-20 talks, China objects to calling Russia invasion of Ukraine a ‘war’

Washington Post November 15, 2022

Negotiations on the joint statement included a fractious debate over the word, with Russia and China pushing hard for another term to describe more than eight months of grinding, bloody military conflict that followed Russia’s full-scale assault of Ukraine, according to delegates. (Wikicommons)

China joined Russia to oppose using “war” to describe Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine in a joint communique at the Group of 20 summit in Indonesia, attempting to undercut an effort by the United States and allies to condemn the conflict in the strongest terms possible.

Negotiations on the joint statement included a fractious debate over the word, with Russia and China pushing hard for another term to describe more than eight months of grinding, bloody military conflict that followed Russia’s full-scale assault of Ukraine, according to delegates.

The final communique is expected to include “war,” though it will likely note that some countries hold differing views on the conflict and its global impact — the language required to seal the deal on the communique. Several developing countries served as a “bridge” between the G-7 and the Russia-China alliance.

China’s opposition to the word “war” highlights how it has tried to play both sides on Ukraine. Beijing has walked a diplomatic tightrope since the start of the invasion, at times appearing to distance itself from Moscow while maintaining that Russia has “legitimate security concerns” and the “ultimate culprit” in the conflict is the United States and NATO. That dual approach is under strain as China tries to tell different stories to its home audience and international interlocutors.

In negotiations, its delegates argued that the G-20 was not the right forum to discuss security issues, delegates said. But the Western countries and their allies countered that the war was having an effect on the world economy, particularly on energy.

China’s Foreign Ministry did not immediately respond to questions about China’s stance during communique negotiations.

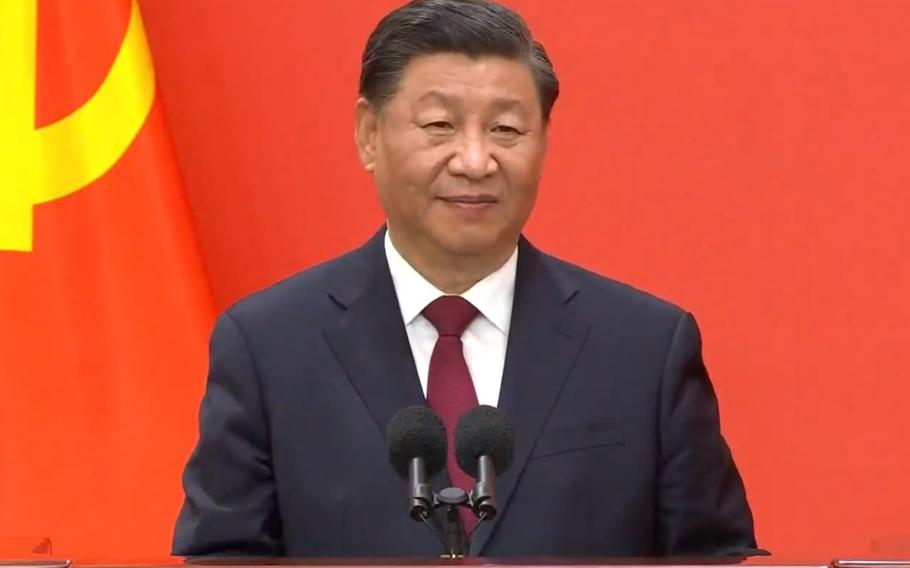

In President Xi Jinping’s first overseas visit since securing a third term — and only his second trip abroad since the start of the pandemic — the Chinese leader has sought to defuse tensions with the United States and allies in the wake of the Ukraine war, which Beijing has refrained from condemning.

Despite the charm offensive, China remains at odds with most other leaders in the group over its continued support of Putin, underscoring Xi’s reluctance to sacrifice a carefully cultivated strategic partnership with Russia to regain trust in Western capitals. On Monday, China was one of 14 countries to vote against a United Nations resolution calling for Russia to pay war reparations to Ukraine.

Xi’s rejection of the threat or use of nuclear weapons in Ukraine during a meeting with German Chancellor Olaf Scholz in Beijing last week was seen by some in Europe as a sign that he was losing patience with Russia after nearly nine months of fighting and its occasional veiled threats to use such arms. But the Chinese readout of Xi’s three-hour meeting with President Biden on Monday made no similar mention of nuclear arms.

Beijing is “trying to get the most out of the nuclear weapons rhetoric” and “trying to leverage a common position into improved relations with Europe,” said Amanda Hsiao, senior China analyst at the International Crisis Group. The stance Xi voiced with Scholz has long been China’s policy on nuclear weapons, albeit one that Beijing had not previously stated when talking about Ukraine.

China has often used discussions with European leaders as an opportunity to adopt more critical language about Russia’s invasion. It was in a meeting with his French counterpart in March that Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi for the first time called the conflict a “war.” Chinese diplomats have largely avoided the term since.

Unlike when meeting Europeans, China appears less willing to side with the America against its partner. “The fact that they only referenced [opposition to nuclear weapons] obliquely in the Xi-Biden meeting readout suggests discomfort with appearing aligned with the U.S. on this issue and was likely meant as a reassuring gesture to Moscow,” Hsiao said.

Wang later told Chinese media that Xi had reiterated China’s position that “nuclear weapons cannot be used and a nuclear war cannot be fought” in talks with Biden.

China is cautious about using the word “war” because it sympathizes with Russia’s position and dislikes the United States strengthening its alliances in response to the conflict, said Ren Xiao, a professor of international relations at Fudan University.

Ren added that Russia’s diplomatic importance to China makes it impossible to interrupt normal economic relations between the two countries. “China will not deliberately alienate Russia to move closer to the United States and Europe,” he said.

After the more upbeat tone of Biden’s meeting with Xi following months of simmering tensions, a senior Biden administration official on Tuesday would not address which countries or how many have signed onto to the strong language for the final statement — or whether China was among those siding with Russia in arguing against such a condemnation.

The official, speaking on the condition of anonymity to offer an assessment of G-20 talks, said that “most” of the G-20 countries were expected to sign onto a strong condemnation of Russia’s war in Ukraine and the statement would “make clear that Russia’s war is wreaking havoc for people everywhere and for the global economy as a whole.”

“It will be clear that most G-20 members condemn Russia’s and the immense suffering it has caused — both for Ukrainians and for families in the developing world that are facing food and fuel insecurity as a result.”

After the meeting with Xi, Biden told reporters, “I absolutely believe there need not be a new Cold War.”

“I’m convinced that he understood exactly what I was saying, and I understood what he was saying,” Biden continued. That relatively upbeat tone marked a departure from tense exchanges in early meetings of Chinese and American diplomats in the early days of Biden’s presidency.

Beijing’s mixed messaging was on display again on Tuesday when a meeting between Wang and Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov received only a terse write-up in Chinese state media while discussion of the event was partially restricted on Chinese social media.

In his speech to G-20 leaders, Xi did not mention the Ukraine conflict, instead criticizing those who “use ideology to draw lines and engage in bloc politics,” an apparent dig at the United States.

In their meeting Tuesday, Xi told French President Emmanuel Macron that he “hopes France will push the European Union to continue with an independent and positive China policy,” reflecting Beijing’s fear that the continent will adopt similar restrictions on Chinese advanced technology as the United States.

According to the French readout, Xi had “expressed his deep concern over Russia’s choice to continue the war in Ukraine” and joined Macron in affirming commitment to respecting Ukraine’s territorial integrity and sovereignty.

Neither sentiment was present in the Chinese readout, where Xi merely stated that China “advocates cease-fire, cessation of fighting and peace talks.”

“China will continue to play a constructive role in its own way,” it said.

Rauhala reported from Brussels and Tan from Nusa Dua, Indonesia. The Washington Post’s Yasmeen Abutaleb and Matt Viser in Nusa Dua, Lyric Li in Seoul and Beatriz Ríos in Brussels contributed to this report.