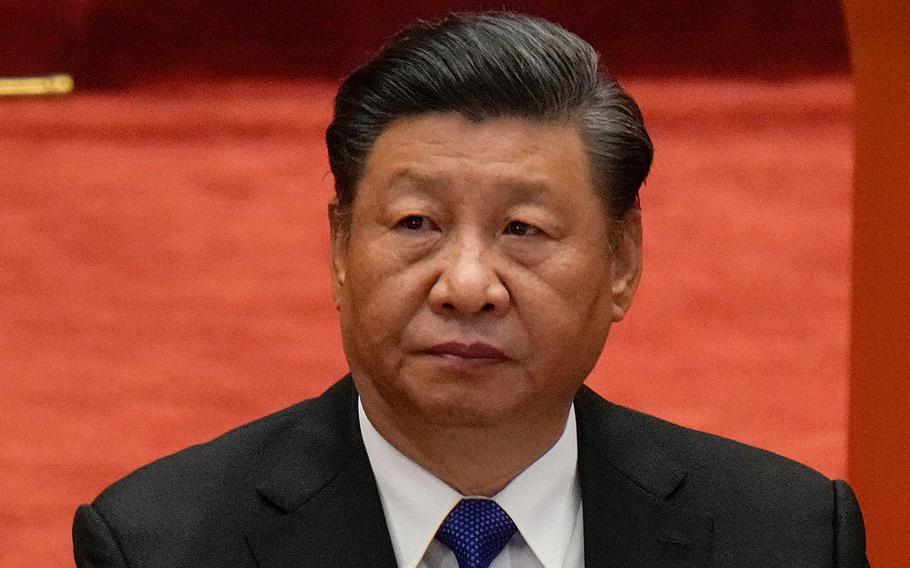

Chinese President Xi Jinping attends an event commemorating the 110th anniversary of Xinhai Revolution at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on Oct. 9, 2021. (Andy Wong/AP)

Does U.S.-style democracy “realize dreams or create nightmares?” It appears to have turned evil like Voldemort, the dark wizard of the Harry Potter franchise. Young President Joe Biden must have eaten too much KFC and McDonald’s, leading to a belief that democracy is like a fast-food chain with the United States supplying the ingredients.

These are among the odd arguments and analogies deployed in recent days during a Chinese Communist Party propaganda blitz to claim that China is as much a democracy as the United States. After China was excluded - along with Russia and other nations deemed autocratic - from Biden’s “Summit for Democracy” this week, Chinese state media, think tanks and officials have lined up to take potshots at the event.

But aside from mudslinging and off-color humor, the campaign also betrays Beijing’s desire to redefine international norms and present its controlling, one-party political system as not just legitimate but ideologically superior to liberal multiparty democracies.

A decade ago, China’s ambition to change the world’s political structures was less clear, but “now I think they genuinely do want to change the world on an ideological level,” said Charles Parton, an associate fellow at the Council on Geostrategy, a British think tank.

The former British diplomat added that the propaganda messages may appear ineffective to Western observers, but they will strike a chord with Beijing’s intended domestic audience and help Chinese leader Xi Jinping legitimize his monopoly on power.

“It’s saying to the Chinese people that ‘We are the best,’ “ Parton said. “The summit is the trigger but more generally China is keen to diminish the ideological power of the U.S. because doing so increases its own.”

The party’s claim to embody a form of democracy is not new. Being a “people’s democratic dictatorship” is written into the constitution of the People’s Republic. But China’s recent defense of its democratic credentials has been unusually direct.

“It’s presented more confidently and much more definitively as a different kind of system and as a rejection of Western-style democracy,” said Mary Gallagher, director of the International Institute at the University of Michigan.

In recent years, the party has preferred to highlight its Marxist roots and talk about the unique nature of “socialism with Chinese characteristics” and its “scientific” approach to governance. Xi has repeatedly declared that liberal multiparty democracy will never work in China.

Even before Xi reasserted party control over Chinese society, calls for liberal democracy were never tolerated. The party has repeatedly crushed demands for free and fair elections, whether during the military crackdown on the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests, jailing dissident Liu Xiaobo in 2009 or silencing critics in Hong Kong.

Global rankings of national democratic institutions regularly label China as an autocracy. The V-Dem Institute, based at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden, ranked China 174th out of 179 countries on its liberal democracy index in 2020. (In the same year, the United States fell to 31st place from 20th in 2016 and 3rd in 2012.)

A white paper released over the weekend by the State Council Information Office, titled “China: Democracy That Works,” suggested that Xi’s recently coined “whole-process people’s democracy” was a legitimate inheritor of the ancient Greek ideal of citizen rule.

The document argues that what matters isn’t any particular process, such as direct leadership elections, but rather the outcome - meeting the people’s needs. Among examples it listed as proof that China’s version of democracy works is “promoting political stability, unity and vitality” and halting the spread of the coronavirus.

One-party rule, rather than being a hindrance to democratization, is its guarantor. “It is no easy job for a country as big as China to fully represent and address the concerns of its 1.4 billion people. It must have a robust and centralized leadership,” the paper stated.

The drier descriptions in official documents have been mixed with colorful commentaries from state media. One by Xinhua News Agency likened the United States to Voldemort - and, by implication, the Chinese Communist Party to Harry Potter - to cast shade on U.S.-style democracy.

“Just like young Voldemort was a star of the wizarding world in his youth, American-style democracy’s early development was an innovation,” the article said. “But just as Voldemort went down an evil path, so has American-style democracy over time gradually changed and decayed.”

The weakening of democratic norms in the United States has emboldened Beijing’s propagandists to be more determined to present the party as building a coherent and superior system of governance.

“The U.S. has long been an example - bad or good - that China pays close attention to,” said Gallagher of the University of Michigan. “If the U.S. struggles in the next few national elections, that will be important in deciding how China moves forward with this re-articulation of its own political system.”

To deflect criticism in multilateral forums, Beijing has increasingly reappropriated contested ideas such as human rights and justified its actions by supplying alternative models.

China has defended the mass internment of Uyghurs, Kazakhs and other mostly Muslim people in Xinjiang as a novel approach to “counterterrorism.” It justifies roundups of human rights lawyers as strengthening China’s “rule of law” and invokes “national security” to crush pro-democratic protests in Hong Kong.

This tactic, which may appear like Orwellian doublespeak to critics, has allowed Beijing to make progress in weaponizing such rhetoric at the United Nations, where it often rebuffs liberal democracies’ concerns by collecting signatures, votes and statements from partner nations.

“What started as a limited, defensive argument has now morphed into a more assertive - you could say aggressive - position that makes sweeping claims about why the Chinese mode of governance is superior,” said Eva Pils, a scholar at King’s College London who studies Chinese law.

After China and Russia’s ambassadors to the United States jointly opposed the democracy summit as the product of a “Cold War mentality,” Pakistan, one of China’s closest diplomatic and military partners, announced on Wednesday that it would not take up an invitation to join.

The extent to which China wants to revise the existing international order is a live debate, but “I would read more recent moves as an indication that the goal is to build a countervailing sphere of influence,” rather than merely weaken liberal principles, Pils said.

- - -

The Wahsington Post’s Lyric Li in Seoul and Pei Lin Wu in Taipei contributed to this report.