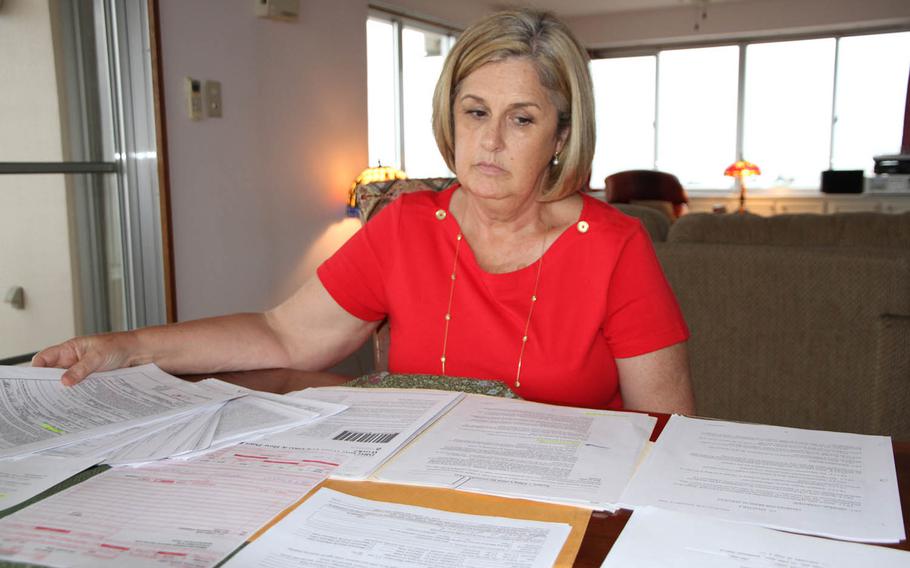

Susan Shelvock reviews paperwork from her Okinawa home related to her hospital bill payments at U.S. Naval Hospital Okinawa. Stars and Stripes spoke with a dozen families over the past seven months facing varying degrees of financial hardship in Japan and Okinawa because of recent medical billing practices. (Matthew M. Burke/Stars and Stripes)

YOKOSUKA NAVAL BASE, Japan — For years, no one did much about thousands of civilian medical bills stacking up at U.S. Naval Hospital Yokosuka.

One hospital employee familiar with the backlog estimated the number of bills that were never sent to patients or insurance companies had reached 20,000 by 2014.

“Oh, we’re working on it,” Beth de la Cruz recalled being told in 2012, after she asked why she hadn’t received any bills in six months.

Over the past 18 months, de la Cruz, a mother of three and spouse of a Naval Criminal Investigative Service special agent, has received bills up to 2 years old, totaling tens of thousands of dollars.

She said she’s lost count of how many midnight calls she has made to the United States, explaining to her insurance company why the bills were so late and were riddled with coding errors.

De la Cruz had to follow up with calls to Centralized Receivables Service, set up by the Department of Treasury as a pilot project for bill collection across the government’s myriad agencies. All of the Navy’s 26 hospitals worldwide are now using CRS, according to service officials in Washington — a decision that came after a Defense Department inspector general report about the Navy’s Portsmouth, Va., hospital showed lax, often nonexistent collection efforts. The IG found 1,533 accounts that were more than 180 days delinquent, with little action taken to collect.

If that IG report reflects procedures throughout the Navy system, it is likely that its hospitals have been unable or unwilling to collect millions of dollars.

In an era of tightening defense budgets, the uncollected medical debt issue goes beyond the Navy. The IG recently announced a review of Army hospitals, after finding $73.1 million in delinquent debt at Brooke Army Medical Center in 2014.

The Navy began using the CRS system last year as its financial remedy for medical billing and collection issues. Navy officials say the new system makes it easier for hospitals to locate patients, send bills and collect payments.

But the transition hasn’t gone smoothly for overseas patients like de la Cruz.

CRS forwarded her $2,500 bill — receipts provided to Stars and Stripes show that she paid on time — to FedDebt, the Treasury Department’s more aggressive collection agency. FedDebt immediately added about $800 in late fees to the balance.

FedDebt’s response to her pleas for a refund? Talk to CRS — which said she should call the hospital.

“It will take an act of God, if at all, to get them to resolve this,” de la Cruz said in February.

De la Cruz did receive a partial refund in April but is still pursuing the full amount.

Stars and Stripes spoke with a dozen families over the past seven months facing varying degrees of financial hardship in Japan and Okinawa connected to hospital billing errors or difficulties with CRS and FedDebt. Bills have been delayed and medical procedures have been coded incorrectly, causing insurance companies to refuse payment to patients.

The process affects a wide range of civilians, including those who support the Navy’s 7th Fleet — shipyard workers, teachers, criminal investigators, intelligence analysts, entertainment coordinators and family support specialists.

Former Yokosuka hospital employees who spoke with Stars and Stripes attributed some of the problems to obsolete computer systems, persistent staff shortages and a disconnect between billing and coding departments. A decision in August by Yokosuka to require patients to file their own insurance claims — which was followed by Okinawa and other hospitals in Japan — has added to the burden, patients say.

Changing the process

The Bureau of Medicine and Surgery is the headquarters command for Navy Medicine, which oversees health care for sailors and Marines worldwide, along with families and retirees.

Bureau personnel told Stars and Stripes that for years, Navy hospitals didn’t follow federal billing regulations.

A former Yokosuka hospital employee familiar with operations there said that problems had been building up for years.

“It’s a sorry state of affairs,” the former employee said. “It’s been that way for a long time and they’re just doing something now. It’s way too late. Around 2011, everything started going bad.”

Staffing shortages were regularly a problem, said the former employee.

Employees from the coding department would pitch in on billing, but with little training.

Other times, the billing and coding departments would have different employees enter patient information from the same bill twice — leaving a greater margin for data entry error and increasing the chances that insurance would reject the bill.

Navy Medicine officials acknowledged that hospitals had trouble finding people who had moved multiple times, which often led to unreceived bills and uncollected debt.

The CRS system has given the Navy a better way to locate people, said Bill Condin, Navy Medicine’s uniform business office program officer.

“CRS can find addresses before it goes to FedDebt,” Condin said. “That gives patients more time to keep in a compliant process.”

The Treasury has a built-in incentive to collect debts, getting “some percentage from DOD for providing the service,” Lt. Cmdr. David Bentley, the Okinawa hospital’s comptroller, said at a town hall meeting in December.

CRS improvements for patients include a longer time before bills are considered overdue and a commitment to make sure that patients receive bills within 60 days of hospital visits. Yokosuka also began sending bills electronically on March 1 to patients who provide email addresses, said Lt. Michael Owen, the hospital’s comptroller.

Navy Medicine officials said CRS began extending the 30-day period to pay bills to a 60-day period in July, following discussions with the hospitals. However, some patients in Japan received bills showing 30-day deadlines even after the July change.

In such cases, or others where patients find errors, patients should follow the instructions on CRS bills that show them how to file for payment waivers, Condin said.

Condin’s goal is that hospitals meet the 60-day billing standard or get Navy resources to make that happen.

Too little, too late

Susan Shelvock’s struggles with the billing system stretch back to 2008, when she and her husband, Robert, were stationed in Daegu, South Korea.

They received $7,500 in hospital bills they say were about 18 months old; their insurance company said it wouldn’t pay because the coding was incorrect. The medical command wouldn’t wait for the problems to be fixed before demanding payment, said Robert Shelvock, a Defense Department schoolteacher.

“They wanted it all right away,” he said. “They sent me a letter of indebtedness, and when that happens, they just start jerking it out of your pay.”

The Shelvocks eventually sought bankruptcy protection. They had been slowly rebuilding their credit when they received notice that an Okinawa hospital bill for $39, which they say they never received, had been forwarded to FedDebt, which added its fees.

Late last year, Okinawa’s naval hospital stopped directly billing insurance companies — a decision that the Shelvocks say threatened their financial stability once again.

Just before Christmas, Susan Shelvock suffered chest pains. In February, they received the bill from CRS for a one-night stay in intensive care — $10,736.73, due in full in 28 days.

“What kind of person can afford to pay that up front?” Robert Shelvock asked. “We had to cancel her follow-up appointment because we can’t afford it.”

The Shelvocks requested a meeting with the hospital’s commanding officer but said they were denied. They ended up speaking to an officer who said the hospital couldn’t resolve their troubles.

That’s when Susan Shelvock reached her boiling point.

She says she was ready to stage a public protest in February at the U.S. consulate in Okinawa in the faint hope that someone in government would recognize the civilians’ struggle with the dysfunctional system.

“There comes a point where you have to stand up and say, ‘I’m sick of this,’ ” she said.

But first, she checked with a military lawyer, who politely informed her that if she staged the protest, she could be subject to arrest by the Japanese police, loss of her Status of Forces Agreement visa and deportation.

The Shelvocks filed their insurance claim through Aetna, only to receive a message a few weeks later: claim denied due to insufficient cost itemization from the hospital.

The hospital later agreed to send in the standard form to Aetna that it once used, but the issue hadn’t been resolved as of April.

Ongoing hurdles

Spend an hour talking with Randy Ricks, and he might get through the litany of hospital billing grievances brought to him by teachers in Okinawa.

“We recently had somebody contact us who received a bill that is 5 years old,” said Ricks, union representative for Defense Department teachers in Okinawa. “Needless to say, there’s no insurance company that’s going to pay that.

“We’re also concerned [that] in some cases, credit bureaus are being notified. This is even happening when a member is not aware of the debt yet.”

After the hospitals stopped billing insurance companies directly, the teacher’s union forwarded 11 recommendations to the Federal Labor Relations Authority and the Office of the Secretary of Defense.

The recommendations are generally aimed at making billing more transparent and providing patients with adequate time to receive and pay bills.

“What we’re proposing is that any bill a year old or more should be waived by the medical treatment facility, because that’s their error,” Ricks said. “It’s almost like they’re just trying to clean out their drawer.”

Navy Medicine said it doesn’t have the authority to waive old bills that insurance companies no longer want to pay, but one person does: Secretary of the Navy Ray Mabus.

“We’ve asked all hospitals to pull those bills aside, and [we] began the negotiation process with the secretary of the Navy about getting a bulk waiver,” Condin said. “Those negotiations are in process right now.”

Stars and Stripes reporter Matthew M. Burke contributed to this report.

slavin.erik@stripes.com Twitter:@eslavin_stripes

Editor's Note: An earlier version stated the Naval Hospital's location was in Portsmouth, N.H. The correct location is in Portsmouth, Va.