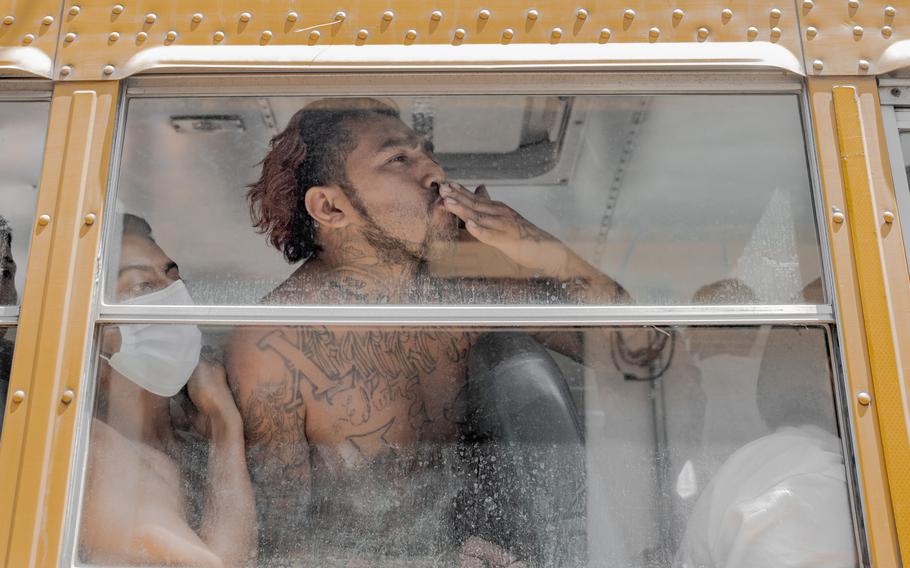

A detainee blows a kiss to relatives at El Penalito. (Fred Ramos for The Washington Post )

SAN SALVADOR - Gregoria Monterosa steeled herself and walked up to the entrance of the unmarked prison known as El Penalito. Next to the front gate, a visibly bored police officer sat behind a desktop computer.

"Who's next?" he droned. Monterosa, 70, stepped forward.

"My son was arrested eight days ago and we still have no idea where he is," she said.

She spelled out his name - Genaro Godoy Ramos - and tried to hold the officer's attention. But he looked over her shoulder, distracted by what he saw there.

Behind Monterosa was a scene provoked by one of the most dramatic police crackdowns in recent Latin American history: a crowd of Salvadoran mothers and wives whose husbands and sons had been detained in a wave of at least 13,000 arrests.

The arrests are El Salvador's response to a rampage of killings last month, including 62 in a single day. The country's president, Nayib Bukele, promised revenge: "A war on gangs."

On March 27, he announced a 30-day "Regimén de Excepción" - a state of emergency that gave the government broad power to make arrests, suspending due process.

Flor de Maria Erazo, 49, cries over seeing her son at the detention center. (Fred Ramos for The Washington Post )

Many family members, like Monterosa, have no idea where their relatives have been taken. They come here on their own ad hoc searches, sneaking glimpses between gaps in the metal gate, checking incomplete lists of detainees posted by police officers.

Monterosa had tried those options without success. Other mothers had seen their sons flash by in the windows of police buses as they were transferred between jails. She watched them collapse into tears, jealous of their assurance.

"At least they've seen their loved ones," she said.

Her son, 47, had been detained immediately after arriving in San Salvador on a deportation flight from the United States. A family friend recorded a video of him and two other deportees being driven away from the country's migration office in the back of a police pickup.

A police officer told the family that his tattoos suggested possible gang ties - evidence enough to detain someone under the country's current state of emergency.

The other women in line at El Penalito told stories of how their sons were arrested - in raids on their homes, while selling fruit in downtown San Salvador or working on construction sites, while walking home from the bus.

In a country where thousands disappeared during the civil war of the 1980s, and thousands more vanished during a surge in gang violence that began in 2014, the arrests have prompted the kind of frantic search that for some Salvadorans feels familiar.

"We have no record of your son in the system," the officer told Monterosa. He called the next woman in line.

Monterosa tucked his identification card back in her purse and walked away.

"How is it that my son can just be lost?" she asked. "How do you arrest someone and then just have no record of it?"

Bukele, a prolific user of social media, has posted videos of prisoners being handcuffed and herded into prison halls, where hundreds were sandwiched together for a photo op.

"We seized everything from them, even their mattresses," he tweeted. "We rationed their food and now they will no longer see the sun. STOP KILLING NOW or they will pay for it too."

Long before the bloodletting last month, it was clear that in parts of El Salvador, gangs had more control than the state. In some neighborhoods, MS-13 and Mara 18 extorted and threatened people, and killed those who refused to submit. The police rarely intervened.

The United States has said that Bukele's government negotiated a truce with the country's major gangs, a controversial approach pursued by previous Salvadoran presidents. The U.S. Treasury Department said last year that Bukele's administration "provided financial incentives to Salvadoran gangs MS-13 and 18th Street Gang (Barrio 18) to ensure that incidents of gang violence and the number of confirmed homicides remained low."

Bukele denies such a truce ever existed.

The 40-year-old former mayor of San Salvador, a self-styled millennial populist, was elected president in 2019 on promises of a break from the past. He's the first president since the 1980s who was not from one of the two parties associated with the country's civil war. His party later won a majority in congress.

Bukele quickly became a vocal ally of then-President Donald Trump, who he called "very nice and cool" before a bilateral meeting in 2019. His relationship with the Biden administration - especially during the current crackdown - has been far more combative.

The State Department, concerned about the state of emergency, urged El Salvador last week "to protect its citizens while also upholding civil liberties, including freedom of the press."

Bukele's response was swift.

"Yes, we got support from the U.S. government to fight crime, but [that] was UNDER THE TRUMP ADMINISTRATION," he tweeted. "You are only supporting the gangs and their 'civil liberties' now."

The state of emergency allows authorities to hold people swept up in police raids without charges for up to 15 days under "administrative detention." Judges then hold virtual hearings for as many as 150 defendants at a time, where most have been ordered to six months of "preventive prison," which can be extended, before they are tried formally.

The flurry of arrests has been so sudden and chaotic that in some neighborhoods, residents say, police are rounding up every young man they find outside of their homes. In some cases, authorities have arrested minors and sent them to adult penitentiaries.

"There's usually no evidence at all, just suspicion," said one judge, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to avoid retaliation by the government. "People arrive in the court and there's literally nothing to substantiate claims that they have gang ties."

Judges who refuse to impose lengthy sentences have been threatened publicly by Bukele, who has called them "accomplices" of organized crime. This week, lawmakers from Bukele's party approved legislation to build more prisons to accommodate the surge in arrests.

And yet, in at least some neighborhoods, gang control has receded during the crackdown. Some Salvadorans have pointed to the sudden disappearance of gang checkpoints, replaced in some cases by police and military patrols.

"Sometimes it's the bitter medicine that's necessary," said the Rev. Mario Carias, an evangelical pastor in the Distrito Italia neighborhood, which has for years suffered a large MS-13 presence.

But in many cases, fear of gang violence has been replaced by fear of arbitrary arrest.

In the Panchimalco area, in the hills outside of San Salvador, soldiers took over a local school, using it as a base for patrols through the scattered shacks perched over slopes.

One day last week, family members say, they detained 19-year-old Johny Melara while he was in his uncle's hammock and 30-year-old Juan Vázquez while he played with his 2-year-old son.

Neither of their families has been able to locate them.

"I look at the bed where my son used to sleep and it's so painful that I don't even know where he is," said Sebastiana Melara, Johny's mother.

She had written a letter to the country's director of prisons and was delivering copies of it to detention centers across the city.

"Estimado señor," it began. "Can you give me information about my son?"

"He was arrested on April 14. It is for this reason that I come seeking help to know where he is detained and when the hearing will be held and the procedures that I have to pursue to feed him and other things that you request."

She said she has not received any response.

In front of El Penalito, Gregoria Monterosa decided she needed to be more assertive. She returned to the prison gate and showed officers there a cellphone video of her son's detention in front of the migration processing office.

The officer turned again to his desktop computer.

"I see him in the system now," he said.

He was in a different prison. The official charge was "resistance," which usually means suspicion of gang involvement.

"Thank you," Monterosa said, walking away from the prison, a look of relief washing over her.

"At least now we know where he is."