Americas

Bolsonaro once said he’d stage a military takeover. Now Brazilians fear he could be laying the ground for one.

The Washington Post July 23, 2021

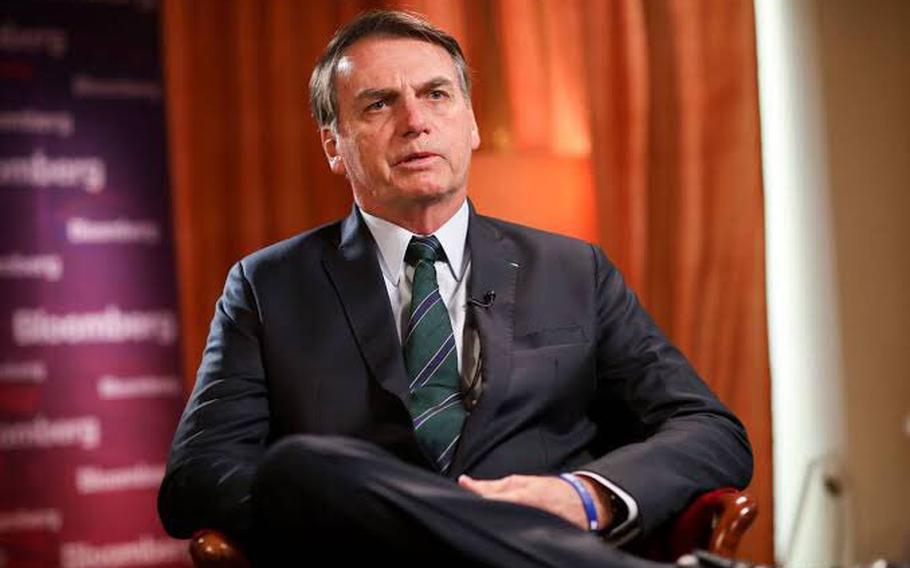

Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro (Jair M. Bolsonaro/Twitter)

RIO DE JANEIRO — In a television interview two decades ago, the fringe congressman didn’t hesitate to say it: If he were president, he would shut down the Brazilian congress and stage a military takeover.

“There’s not even the littlest doubt,” Jair Bolsonaro said. “I’d stage a coup the same day [I became president,] the same day. Congress doesn’t work. I’m sure at least 90% of people would party and clap.”

Now the congressman is president of Brazil, and fears are mounting here that he could be considering how to make good on that plan. Bolsonaro, a former army captain who has frequently lamented the collapse of Brazil’s military dictatorship, has in recent days wondered not only whether he will participate in next year’s elections, but also whether there will even be elections.

“Next year’s elections have to be clean,” he declared this month. “Either we’ll have clean elections, or we won’t have elections.”

Some of the most powerful political voices in the country, including that of former president Michel Temer, are expressing concern that Bolsonaro could try to leverage unsubstantiated claims of electoral fraud to derail or overturn a vote he has lost.

“The situation is extremely worrying in Brazil,” said Marcos Nobre, a prominent political scientist at the State University of Campinas. “It’s very, very grave what is happening here.”

Bolsonaro’s increasingly brazen comments escalate a monthslong, Trump-style campaign to erode faith in the electoral system and transform its processes into a high-stakes political struggle. Now, as Latin America’s largest democracy girds itself for what is expected to be a tumultuous election, it confronts a paradox that will be familiar to Americans: The man leading the assault on its electoral process is the very person most recently awarded its highest office.

For years, Bolsonaro has lodged unsubstantiated allegations of electoral fraud. Before the 2018 presidential election, he said the only way he would lose would be by fraud. He then claimed he had won by much more than the official tally showed. Last year, he parroted President Donald Trump’s allegations on the U.S. election: “There was a lot of fraud there.”

But in recent months he has increasingly latched onto Brazil’s electronic voting machines, alleging without evidence that the system is pervaded by fraud. He says the country should switch to physical ballots and has repeatedly pushed the congress to make that change.

This week, he cast Brazil’s electoral process as part of a broader conspiracy by unnamed forces to return leftist politician Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva to the presidency. Lula, who was jailed on corruption charges and later released, is now leading Bolsonaro in presidential polls.

“The same people who took Lula out of jail and made him eligible to run for office will be secretly counting the votes inside the Superior Electoral Court,” he said this week. “Elections that you can’t audit, this isn’t an election — it’s fraud.”

In a statement, Bolsonaro’s presidential office defended Bolsonaro as an “active and tireless defender of democracy and the Brazilian constitution.” The officials said Bolsonaro wants a verifiable process in which every vote is honored.

“Brazil will continue to be a thriving democracy, with total respect given to the constitution and the will of the people to choose their representatives,” the Bolsonaro officials said.

Few think Bolsonaro would have any real chance of undoing an election. If anything, analysts say, his rhetoric betrays his political weakness. His approval ratings have fallen to record lows. The coronavirus has killed more than 545,000 Brazilians, and congressional investigators are probing his government’s hands-off response to the pandemic. He’s being investigated on allegations he failed to report suspicions of government corruption in the purchase of an Indian vaccine.

“I don’t see a possibility of a military coup in Brazil,” said Raul Jungmann, a former defense minister. “There are neither the internal nor the external conditions — not to mention there’s little desire among the armed forces to set out on an authoritarian adventure.”

But in a country freed from the yoke of a military dictatorship only in 1985, and which has warily eyed the military’s involvement in politics ever since, there is also the sense that anything is possible.

Bolsonaro has stacked his administration with a historically large number of military officials. His policies enjoy widespread approval among security forces. A portion of his base has repeatedly called on him to stage a military takeover — pleas he’s fanned by attending their rallies. After Trump supporters in the United States assaulted the U.S. Capitol to try to overturn the election results, Bolsonaro warned that Brazil would “have an even worse problem” if it didn’t change its electoral system. His defense minister, Braga Netto, has also reportedly threatened to cancel the elections if the country didn’t use paper ballots — a newspaper report Netto denied Thursday morning.

“Even if it is just a hypothesis, it would be democratically negligent to not be worried by this,” said Luiz Eduardo Soares, a prominent political analyst. “His behavior has been repeatedly threatening and hostile toward institutions.”

In a country polarized by Bolsonaro’s presidency, a sustained assault on the legitimacy of the election could undermine democracy for years to come. Millions could come away from the election feeling that they had been cheated — as has happened in the United States.

“Elections are a huge leap of faith, and it’s amazing that we’ve taken them as an article of faith for this long,” said Christopher Sabatini, a senior fellow for Latin America at the London-based think tank Chatham House.

“The genius of electoral fraud claims is that you don’t even need to demonstrate fraud; you just need to demonstrate the possibility of fraud,” Sabatini said. “Then, in the hothouse environment of social media, it will be picked up with very little fact-checking, really catch fire and be reinforced.”

Lilia Moritz Schwarcz, a University of Sao Paulo anthropologist and visiting professor at Princeton, said Brazil today is haunted by the “specter of a dictatorship.” But it’s not the lingering effect of its decades under a military regime, she said — it’s the fear of Bolsonaro’s apparent authoritarian impulses.

“We have a president who was formed by the military, who talks all of the time about the dictatorship, who has conducted anti-democratic acts,” she said. “He clearly wants to weaken Brazil’s institutions.”