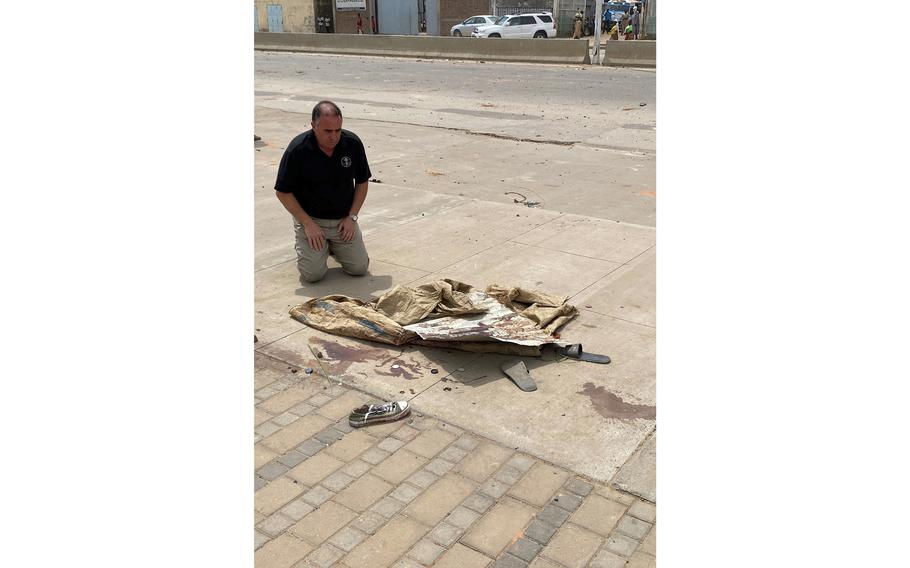

U.S. Ambassador Alexander Laskaris kneels on a bloodstained sidewalk in N’Djamena. (U.S. Embassy N'Djamena)

N'DJAMENA, Chad — Western officials are increasingly concerned about the stability of Chad, a central African country that has been one of the United States' most important security partners in a region confronted by widening Russian influence and several Islamic insurgencies.

The threats Chad is facing are underscored by several leaked U.S. intelligence documents, which describe an effort by Russia's paramilitary Wagner Group in February to recruit Chadian rebels and establish a training site for 300 fighters in the neighboring Central African Republic as part of an "evolving plot to topple the Chadian government." The previously unreported documents detail a discussion early that month between Wagner's leader, Yevgeniy Prigozhin, and his associates about the timeline and facility for training an initial group of rebels in Avakaba, close to the Chadian border, and the route that Wagner would use to transport them.

These security concerns have contributed to a muted response from the United States and some other Western governments to Chad's increasing repression at home, critics say, most notably the killing of scores of largely peaceful protesters by security forces in October. At the time, Chadian officials said that 50 people had died, but the Chadian Human Rights Commission has subsequently reported that at least 128 people were killed, and some human rights advocates now believe the number was much higher.

The debate over how far the United States can push Chad and whether this could jeopardize security interests in Africa exemplifies the challenges facing Western foreign policymakers who seek to support allied governments and also advance democratic values. Analysts say that Russia's campaign to project greater influence in Africa has raised the stakes.

In a sharply worded letter to Secretary of State Antony Blinken last month, Sen. Robert Menendez (D-N.J.), chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, wrote that he was "extremely concerned by the lack of clear, public U.S. response" to the October killings in addition to continued U.S. support for Chad's military. The risk, Menendez wrote in the letter, which has not previously been reported, is "creating a perception … that the United States is willing to partner with regimes that do not respect democracy and human rights as long as such regimes agree to cooperate on countering terrorism and opposing malign Russian influence."

Michelle Gavin, an Africa expert at the Council on Foreign Relations, said that the U.S. foreign policy needs to do a better job of recognizing that efforts to promote security and democracy are linked. Chad's repression of its own citizens is a sign of the government's internal weakness and raises the question of how good a security partner it can be, she said.

"We have fundamentally failed to reckon with the stability of the Chadian state," she said. "It feels like at any moment, all of the eggs that we have placed in this basket could fall out the bottom."

Rebellion is woven into the history of Chad, a sprawling nation of 16 million that is home to dozens of ethnic groups vying for power. Former president Idriss Déby, who was killed in 2021 on the battlefield, tamped down multiple rebellions during his 30-year reign, sometimes with the support of Chad's former colonizer, France. Chad has been led by Déby's son, Gen. Mahamat Idriss Déby Itno, since 2021.

What has changed is Russia's involvement, which has expanded in Africa as France's popularity has fallen. A Western diplomat in Chad, who like other diplomats spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive foreign policy issues, said that Chad faces the possibility of an internal coup in addition to threats from rebels based just over its borders in Libya, Sudan and the Central African Republic. The Wagner paramilitary group has ties with armed forces or militias in each of these countries.

"They have thousands of reasons to be worried," said another Western diplomat, referring to threats against the Chadian government from outside and inside the country. Western officials, he said, are closely watching developments and "increasingly concerned."

The leaked U.S. intelligence documents say the efforts to foment a rebellion in Chad are part of a broader push by Prigozhin to create a "unified 'confederation' of African states" across the breadth of the continent, including Burkina Faso, Chad, Eritrea, Guinea, Mali, Niger and Sudan. "During the last year, Prigozhin has accelerated Vagner operations in Africa, shifting his approach from taking advantage of security vacuums to intentionally facilitating instability," one document says.

The documents are part of a trove of images of classified files posted on Discord, a group chat service popular with gamers, allegedly by a member of the Massachusetts Air National Guard.

Chadian intelligence believed that two Chadian nationals traveled in late February to Bangui, the capital of the Central African Republic, at Wagner's invitation to help recruit fighters from Chad and the Central African Republic in a Wagner-funded plot "to destabilize the Chadian regime," according to the documents.

The two Chadian nationals, who are named in the documents, stayed at the Ledger Plaza Bangui Hotel, where they were reportedly received by Defense Minister Rameaux Claude Bireau of the Central African Republic, which has been engaged with Wagner since 2018. As part of this effort, the two Chadian nationals were working with the CAR government to convince rebels specifically of southern Chadian origin to work alongside Wagner, the documents say.

Contacted for comment, Prigozhin replied with obscenities and said the reports about his involvement with a planned rebellion in Chad were "nonsense."

Chadian Communications Minister Aziz Mahamat Saleh did not specifically address the U.S. intelligence information but said in an interview in N'Djamena this month that the government is aware that "many young people" from Chad have joined Wagner in the Central African Republic.

Saleh said his country does not have problems with Russia but cannot accept apparent efforts by Wagner to interfere with Chad's internal politics. He said that Wagner has turned up in other African countries when their governments needed help holding onto power, which he said will not be the case in Chad. "We can defend ourselves," he said.

The Central African Republic's communications minister did not respond to requests for comment.

In February, the Wall Street Journal reported that the United States shared intelligence with authorities in Chad indicating that Wagner was potentially planning to assassinate Déby.

A senior State Department official said the United States "is committed to a democratic transition in Chad" and is continuing to press for the release of 150 political prisoners who are in custody. Although Chad has been an "important partner" in counter-terrorism operations in the Sahel and the Lake Chad Basin, the official said, that "has no bearing on U.S. views on the longstanding need for democratic reform in Chad."

A spokesman for U.S. Africa Command, which oversees military operations on the continent, said Chad has been "a very willing and capable partner in fighting terrorism" and understands the dangers that Wagner poses to African countries.

Tensions were already running high when thousands of pro-democracy protesters took to the streets in N'Djamena on Oct. 20, 2022, to oppose a government plan to extend its hold on power for another two years. Security forces responded by firing tear gas and live ammunition at protesters, chasing them into homes and arresting hundreds. It was the single bloodiest day in Chad in decades.

A young doctor remembers hearing the crack of gunshots followed by screaming. Then dozens of wounded young men and women began streaming into the hospital in N'Djamena, he recalled. The doctor, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because of fear of retribution, said he saw at least 10 dead bodies in the emergency room. There were so many wounded, he said, that the hospital was "completely overwhelmed."

"It was completely horrible," he said, "and now everyone fears talking about that day because we do not want to be arrested."

Delphine Djiraibe, a Chadian human rights lawyer who shielded young protesters at her house in N'Djamena, said there were so many dead bodies at the morgue that they rotted before their families could collect them and give proper burials.

"People are living with fear. We don't know what will happen in the next minute," she said. "And the international community has been too quiet."

That day marked a turning point, said another Western diplomat, noting that any hope that Déby might be more open to democracy than his father had been dashed. "All of us are losing trust and hope," he said.

Saleh, the communications minister, said that the government is committed to holding elections in 2024 and is focused on making Chad a more inclusive country, pointing to a recent decision by the president to pardon more than 300 rebels.

But a Western diplomat added that a decision by Chad's government to expel the outspoken German ambassador this month — citing his "discourteous attitude" — sent a clear message to the rest of the diplomatic community: "If you criticize them, you are out."

On that tragic day in October, the U.S. Embassy in N'Djamena posted a picture of Ambassador Alexander Laskaris kneeling on a bloodstained sidewalk, and the State Department urged "all parties to deescalate the situation and exercise restraint."

In the months since, the U.S. government has been largely silent about the killings. Menendez noted in the letter to Blinken that the United States has not imposed travel restrictions or sanctions on those responsible for the violence, as was done following a 2009 massacre by security forces in Guinea. The Biden administration has never condemned Déby's seizure of power a "coup," the letter noted, and invited him to Washington for the "Africa summit" last year.

Menendez has frozen some funding for security cooperation, which a U.S. official in Chad said has meant that training and equipment for Chadian soldiers deployed with the United Nations have been frozen. But the senator said in the letter that other assistance has continued to flow to Chad's military.

Remadji Hoinathy, a researcher with the Institute for Security Studies in N'Djamena, said that Chad and the West are playing a high-stakes "bargaining game." Chad's bet, Hoinathy said, is simple: "Don't talk about my human rights abuses, and I will support you."

Cameron Hudson, a senior associate at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, said the Biden administration has struggled to achieve a clear policy on the Sahel region of Africa, in part because there has not been an active discussion about how to balance both promotion of security partnerships and democracy.

"We have to do both at the same time," he said. "We need to be able to walk and chew gum."