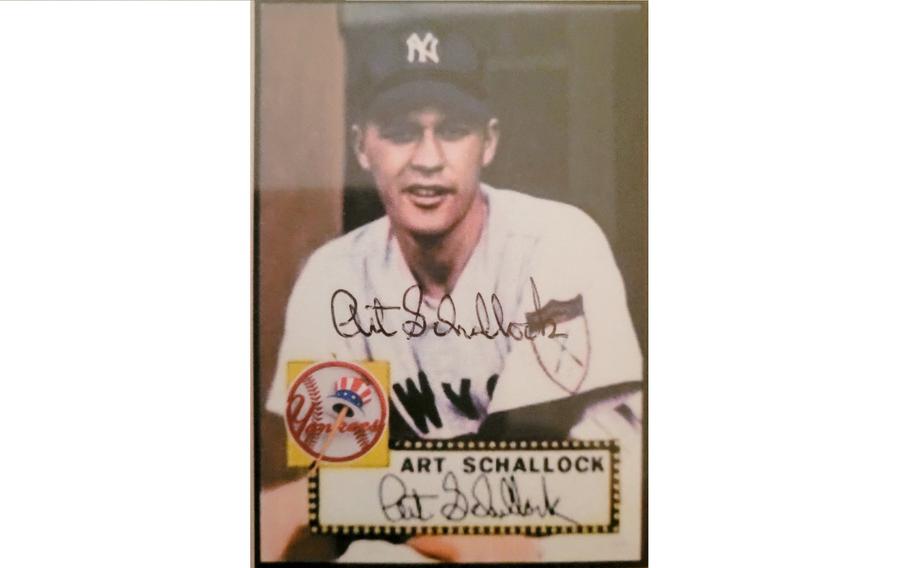

A signed baseball card of Art Schallock during his time as a member of the New York Yankees. The 98-year-old Navy veteran, who pitched for the Yankees, is the oldest surviving MLB player. (Twitter)

(Tribune News Service) — Growing up in Mill Valley, Arthur Schallock didn’t much care for major league baseball. But he was a huge fan of the San Francisco Seals.

Schallock, who will be 99 in April, was a star pitcher at Tamalpais High in the early 1940s. He hoped to play for the Seals, of the Pacific Coast League. The club had been a way station for future Hall of Famers Paul Waner, Lefty Gomez and Joe DiMaggio.

But Seals manager Lefty O’Doul wouldn’t sign the 5-foot 9-inch, 160-pound left-hander, believing him too slight to succeed. Schallock never did play for the Seals. He had to settle instead for the New York Yankees, who signed him in 1951. To clear a spot for him on the roster, the Yankees demoted a struggling rookie to the minors.

“They sent Mickey Mantle down to make room for me,” Schallock recalled with a chuckle during a recent interview at his house near the city of Sonoma, where he lives with Dona, his wife of 76 years. Mantle got his groove back, and rejoined the Yankees a few months later.

In his five seasons with The Pinstripes, Schallock earned three World Series rings. A pitcher with a nasty curve, a “sneaky fastball” and highly effective change-up — “that was probably my best pitch,” he recalls — Schallock was a foot soldier on teams with such household names as DiMaggio, Mantle, Whitey Ford and Yogi Berra.

But Schallock has earned added renown, in his twilight years, for his longevity. On July 7, 2022, a former St. Louis Browns outfielder named George Elder died at the age of 101. With Elder’s passing, Schallock became the oldest living former major league player.

The next oldest living big leaguer, born 131 days after Schallock, is Bill Greason, who in 1954 became the first Black pitcher to play for the St. Louis Cardinals.

“They’re both delightful”

Arthur and Dona are going strong, all things considered. They live an independent life at Creekside Village, near Sonoma.

A former club champion at Peacock Gap Golf Club in San Rafael, he gave up that sport a few years ago, because of “balance issues,” Schallock said. “I’m afraid to bend over — tee it up and fall flat on my face.”

He’s nearsighted now, so Dona does the driving. A spring chicken at 97, she’s also a gifted painter, and a regular at weekly meetings of the Creekside Art Group.

“They’re both delightful — very lively and great with the stories,” said Janice Best, a fellow Creekside artist and friend of the couple.

“And she adores him. She’s so proud of Artie, and it’s just touching.”

The couple met on a blind date in Marin County, after Schallock returned from his three years of service in the Navy during World War II.

“Art has been lucky all his life,” says Dona, a native of Sausalito. But he deserves it. He’s a very nice man.”

Schallock has been on this earth nearly twice as long as his father, who was killed in a car accident at the age of 51. A drunken driver hit him head on. Arthur, 11 or 12 at the time, was sitting in the passenger seat. He went through the windshield.

“They found me in some bushes,” he says. “I woke up three days later, in the hospital.”

Close calls in the Pacific

Two weeks after his high school graduation, he was drafted by the Navy, and shipped off to the Pacific Theater. “I didn’t see a baseball for three years,” he recalls.

Schallock spent most of those three years as a radio operator on an aircraft carrier called the USS Coral Sea — later renamed the USS Anzio.

On Nov. 24, 1943, the Coral Sea was steaming in the central Pacific alongside its sister ship, the USS Liscome Bay, when that escort carrier was torpedoed by a Japanese submarine. The torpedo hit the Liscome Bay’s starboard side, near the bomb magazine.

“Blew the elevators right out of the ship,” recalled Schallock. “It went down in about 20 minutes.” A total of 644 men were killed on the Liscome Bay that morning.

Schallock’s job was to man a kind of crow’s nest high up on the “the island” — the command center for flight-deck operations.

“When those kamikazes started coming around, I was like a sitting duck up there,” he remembers. “Thank God our gunners nailed ‘em before they got to our ship.”

Life in the minors

Discharged in 1946, he signed the following year with the Brooklyn Dodgers organization. A year later, he made the roster of the Dodgers’ Triple A club in Montreal, where his teammates included future Hall of Famer Duke Snider, future Cy Young Award-winner Don Newcombe, and a rangy first baseman named Chuck Connors, who would go on to star in the television series The Rifleman. At Schallock’s request, Montreal traded him to the Hollywood Stars, a PCL team affiliated with the Dodgers. The Twinks, as they were known in the press, were promoted as “the Hollywood Stars baseball team, owned by Hollywood stars.”

Celebrity stockholders included Gary Cooper, Barbara Stanwyck, Gene Autry, George Burns and Gracie Allen, Bing Crosby and Cecil B. DeMille.

Schallock recalls that his wife “loved the Hollywood Stars, rubbing elbows with movie stars and stuff,” although it didn’t seem to bother him, either.

During his three seasons with the Twinks, Schallock dominated his old, favorite team, the Seals. “All I had to do was throw my glove out on the mound, and I’d win the ballgame,” he recalls.

Walking from the mound back to the dugout one day, he crossed paths with O’Doul, the Seals skipper, who said, “You little son of a bitch — I should’ve bought you when I had the chance.”

Schallock pitched a game against the Seattle Rainiers in 1951. Unbeknownst to him, Yankees scout Joe Devine was in the stands. Halfway through the game, Stars manager Fred Haney called Dona down from the stands. He had news.

“I just sold Arthur to the New York Yankees.”

“Who the hell are the New York Yankees?” she replied.

The pinnacle

They were a team in transition. True, the Yankees had won three of the past four World Series. But stars like Tommy Henrich and DiMaggio had departed, or would soon retire. Filling that void were Mantle, pitchers Whitey Ford and Allie Reynolds, and the koan-spouting catcher, Yogi Berra, still relatively young in ‘51. Powered by that nucleus, managed by crusty Casey Stengel, the Yankees would win the next three World Series, as well.

The newest Yankee roomed with Berra on the road that season. “He knew all the hitters on each team, so he went over them with me,” said Schallock, who performed a service for Berra in return. He would buy comic books for the catcher.

The players who weren’t stars, Dona recalled, stayed at the Berkshire Hotel, near Yankee Stadium.

“I was the only one who knew how to cook,” recalled Dona. “So I would charge them for whatever the cost of the groceries were. That’s all I would charge.”

Mantle’s wife, Merlyn, was “so nice. She was adorable,” Dona said.

Those were the days when they had a wives’ box” at the stadium. “So we all knew each other.”

Schallock spent his five seasons with the Yankees on the bubble of the roster, shuttling between the big club and Triple-A. In his six starts in 1951, he won three and lost one, with two no-decisions. His earned-run average was 3.88. Schallock did not see action in that World Series, or the 1952 Fall Classic.

Working mainly as a reliever in ‘53, Schallock’s ERA was 2.95. He pitched the final two innings in Game four of the World Series, giving up two hits and a run in a 7-3 loss to Brooklyn.

The Yankees won the next two games, clinching the series and earning Schallock his third World Series ring.

Early in the 1955 season he was traded to the Baltimore Orioles, winning six games and losing 8. Plagued with an injured throwing shoulder, he retired from baseball the following year.

After baseball

Schallock spent the next three decades working with title companies, in public relations and business development.

People still send memorabilia to him in the mail, asking for his autograph. Sometimes they include some cash, to compensate him.

“I sign the thing, put the money back in the envelope and send it right back to ‘em. What the hell. I don’t need it.”

He remembers that the highest paid person on those dynastic Yankee clubs was the general manager, George Weiss. “He was getting more than Yogi Berra, Mickey Mantle.”

In Schallock’s day, the players’ minimum salary was $5,000. It’s now $700,000.

“I cry a lot about that,” he says. But he’s smiling as he says it.

He has always floated on the surface of things, never letting anything get him too down.

“I try to treat everybody fairly,” said Schallock, who then revealed a glimpse of the philosophy that has kept him around for so long: “I never get mad or upset over anything. It’s not worth it.”

How about on the mound?

“Nahhh,” he replied. “If somebody hit a home run” — like the tape measure shot Mantle hit off Schallock when the pitcher was an Oriole — “well, so what? Move on.”

Speaking of moving on, after his next birthday, he’ll be staring at 100.

“Tell me about it,” he says. “I walk from here to the mailbox, I’m all tuckered out.”

Would he like to hit the century mark?

“I think that ‘d be great,” he says.

Don’t bet against Schallock. His luck’s held out this far.

(c)2023 The Press Democrat (Santa Rosa, Calif.)

Visit at www.pressdemocrat.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.