Jim Brown runs for a gain against Washington in Washington, D.C., on July 15, 1966. (Charles Del Vecchio/Washington Post)

Jim Brown, who was often called the greatest football player of his time but who gave up the sport at the peak of his career in the 1960s, declaring himself a "highly paid, over-glamorized gladiator," and turned instead to acting and activism, died May 18 at his home in Los Angeles. He was 87.

His wife, Monique Brown, announced the death in an Instagram post but did not cite a cause.

Mr. Brown was one of the most gifted all-around athletes of the past century. He excelled in lacrosse, basketball, and track and field and was virtually unstoppable during his nine years as a powerhouse fullback with the Cleveland Browns in the 1950s and '60s.

In breaking almost every rushing record in the National Football League, he "was something completely new," journalist and sports author David Halberstam wrote in 2001. "I have never again seen a running back who was so much better than everyone else who did what he did at the time he was doing it. He dominated his field in his era like few athletes ever have, perhaps matched only by Babe Ruth and Bill Russell."

At 6-foot-2 and about 230 pounds, Mr. Brown had an unmatched blend of strength and speed that enabled him to lead the NFL in rushing in eight of his nine years with the Browns. When he retired after the 1965 season, his 12,312 career rushing yards were a record that would stand for 19 years, until broken by Walter Payton of the Chicago Bears. Mr. Brown ran for more than 1,000 yards in a season seven times, and his 1,863 rushing yards in 1963 stood as the NFL record until surpassed by the Buffalo Bills' O.J. Simpson 10 years later.

Mr. Brown helped lead Cleveland to the NFL championship in 1964 and was elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1971, in his first year of eligibility.

"As a pure runner he stands alone," his coach in Cleveland, Paul Brown, wrote in a 1979 autobiography. "Jim combined power, acceleration, speed and great balance with an inner toughness that never conceded the slightest edge to anybody."

Away from the playing field, however, Mr. Brown could be a complex, contradictory and troubled man. He was arrested at least seven times for assault, usually against women, including a 1968 incident in which he was accused of throwing a girlfriend off a second-story balcony. His career began at the dawn of the civil rights movement, and he was acutely aware of the double standards that prevailed in sports and society.

Even when he was named NFL rookie of the year in 1957, he wasn't always allowed to stay at the same hotels or dine in the same restaurants as his White teammates. Mr. Brown became something of a symbolic figure early in his career, particularly when his team played Washington's NFL franchise, whose owner, George Preston Marshall, stubbornly refused to put a Black player on the roster until 1962.

Washington Post sportswriter Shirley Povich mocked Marshall by noting that Mr. Brown and other African Americans were born "ineligible" to play for the Redskins. In 1960, Povich equated Mr. Brown's exploits on the gridiron with advances in the civil rights movement, writing that the player "integrated the Redskins' goal line with more than deliberate speed, perhaps exceeding the famous Supreme Court decree. Brown fled the 25 yards like a man in an uncommon hurry and the Redskins' goal line, at least, became interracial."

After leading the NFL with 1,544 rushing yards in 1965 and being named the league's most valuable player, Mr. Brown spent the offseason filming the World War II action drama "The Dirty Dozen." When the movie production was delayed, interfering with the beginning of training camp, Mr. Brown stayed with the movie, abruptly retired and never played football again.

He held 15 NFL records at the time, leaving generations of football fans to speculate on what he might have accomplished had he played a few more years.

Mr. Brown was not one to look back.

"I was a symbol of a Black man who wanted all of my freedoms," he told The Washington Post in 1979. "It's very difficult for White America to understand that if you are part of football's elite why you are not satisfied with recognition and good money. . . . As an American citizen, I wanted the same rights as all Americans. Anyone who expected me to be overjoyed that I was doing well in football would be disappointed."

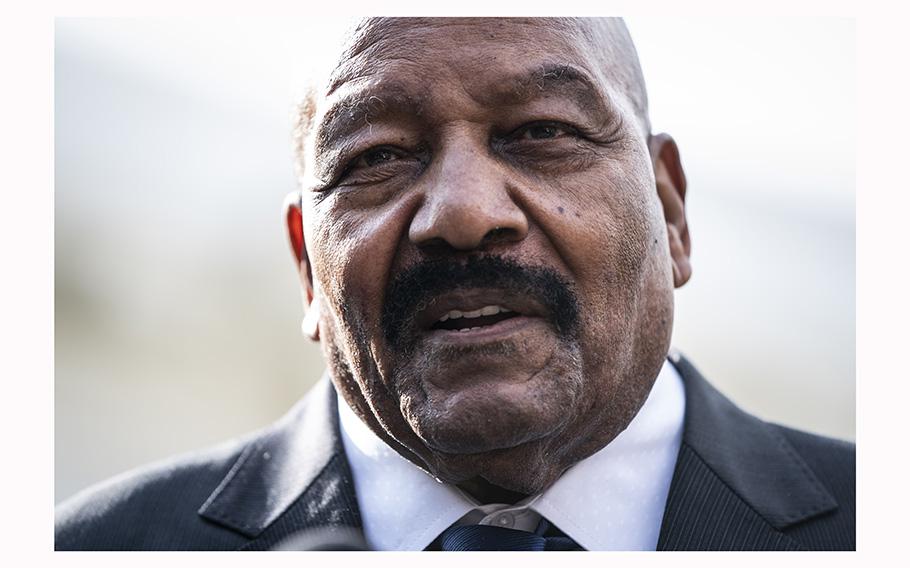

Jim Brown at the White House on Feb. 18, 2020, in Washington, D.C. (Jabin Botsford/Washington Post)

Mr. Brown appeared as an actor in more than 50 movies, many of them action films such as "Ice Station Zebra" (1968) and "100 Rifles" (1969). In the latter, set in early 20th-century Mexico, Mr. Brown played an American sheriff and co-star Raquel Welch played a peasant leader, and they performed one of the first interracial love scenes ever shown on-screen.

"The acting of Mr. Brown, a big, fine-looking chap, is strictly tentative," critic Howard Thompson wrote in the New York Times, "but he does have presence."

Despite his larger-than-life image, no one, it seemed, could fully explain the complexities of Jim Brown. He had a way of feigning weakness but proving strength, on the field and off it.

After carrying the ball, he would slowly pull himself off the turf and hobble back toward the huddle. As opponents relaxed, content that they had slowed him up, he'd carry the ball again, running over would-be tacklers.

Mr. Brown never missed a game in his nine-year career and is the only player in NFL history to average more than 100 yards rushing per game - 104.3, to be exact.

Former Washington defensive back Jim Steffen was once asked how to stop him. "Hold on and wait for help," he advised.

Deeply conscious of the influence athletes held over young people, Mr. Brown often criticized other high-profile Black athletes for ignoring what he considered their responsibility to be role models.

In 1988, he founded Amer-I-Can, an organization aimed at fostering self-esteem and defusing tension among gang members and prisoners.

"The young Black male is the most powerful source of energy and change we have," he told The Post in 1991. "My hope is to start a direction where these young men will be given respect and taught how to utilize it."

In the 1960s, Mr. Brown joined other Black athletes, including Russell, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Muhammad Ali, in calling for social change. His early friendship with Ali was portrayed in the 2020 film "One Night in Miami," in which Mr. Brown was played by actor Aldis Hodge.

Mr. Brown's private life was tumultuous. In his 1989 memoir, "Out of Bounds," he revealed that he often attended sex parties and had extramarital affairs. He was involved in several instances of assaults against women.

His first marriage, to Sue James, ended in divorce in 1972. In 2002, he spent nearly four months in jail for using a shovel to shatter the windows of a car belonging to his second wife, the former Monique Gunthrop, who was almost 40 years his junior. They remained married after his release.

Complete information about survivors was not immediately available.

James Nathaniel Brown was born Feb. 17, 1936, on Georgia's St. Simons Island. His father, a former boxer, abandoned the family, and his mother took a housekeeper's job in New York, leaving her son to be raised by a great-grandmother.

Mr. Brown was 8 when he joined his mother on Long Island, and sports became his refuge. At Manhasset High School, he played football, baseball and lacrosse, ran track, starred on the basketball team and was chief justice of the school's student court. After earning 13 varsity letters, he was offered athletic scholarships by 45 colleges and selected Syracuse University in Upstate New York.

Mr. Brown excelled in basketball and track and field and once finished fifth in a national decathlon competition. He was an all-American lacrosse player at Syracuse and was named to the National Lacrosse Hall of Fame in 1983, 12 years before he was selected to the College Football Hall of Fame.

On the gridiron at Syracuse, he once scored 43 points in a game in 1956 - six touchdowns and seven extra points as a kicker - to set an NCAA record that stood for more than 40 years.

By the time Mr. Brown graduated from Syracuse in 1957, he had earned 10 varsity letters in four sports. The Cleveland Browns made him the sixth selection in the NFL draft, and he turned down offers to play professional basketball and to become a boxer to play football.

The Browns - named for founding coach Paul Brown - had an early legacy of racial integration. In 1946, one year before Jackie Robinson became the first African American major league baseball player of the 20th century, the Browns had two Black players, middle guard Bill Willis and Marion Motley, a fullback whose powerful running style foreshadowed that of Jim Brown.

Paul Brown, who was Cleveland's coach through the 1962 season, struggled to understand his young star and sometimes quarreled with him. In his autobiography, Paul Brown criticized Jim Brown's "lack of effort in blocking, which in some instances was so poor that pass rushers went right past him."

The coach also saw what he considered flaws in his character.

"Jim's biggest problem was his attitude, and his worst enemy was himself," Paul Brown wrote. "By nature he was an unhappy man, it seemed to me. Throughout his time with us he was a loner and never said much to anyone. He had few friends on the team, and none of long standing."

Jim Brown said his coach was part of the old guard in sports - and throughout the United States - that did not appreciate the social changes unfolding at the time.

"Paul represented in general what White America thought at the time," he told The Post in 1979. "White America always felt that Black Americans who enjoyed great status in football ought to be satisfied."

He added: "As far as my blocking was concerned, he was absolutely right. It is difficult to be a racehorse and a plow horse at the same time."

In later years, as his acting roles grew more infrequent, Mr. Brown's rough edges never softened. He continued to counsel prisoners and youths with a no-nonsense message of tough love and had a stormy relationship with his old team, the Browns. Finally, in 2013, the team honored Mr. Brown with a ceremony during a game in Cleveland and named him a special adviser.

It marked one of the few times, since he left the field of play, that Mr. Brown looked back, if only for a moment, at his past glories. For decades, the game of football missed Jim Brown more than he missed it.

"I quit with regret," he said, "but not sorrow."