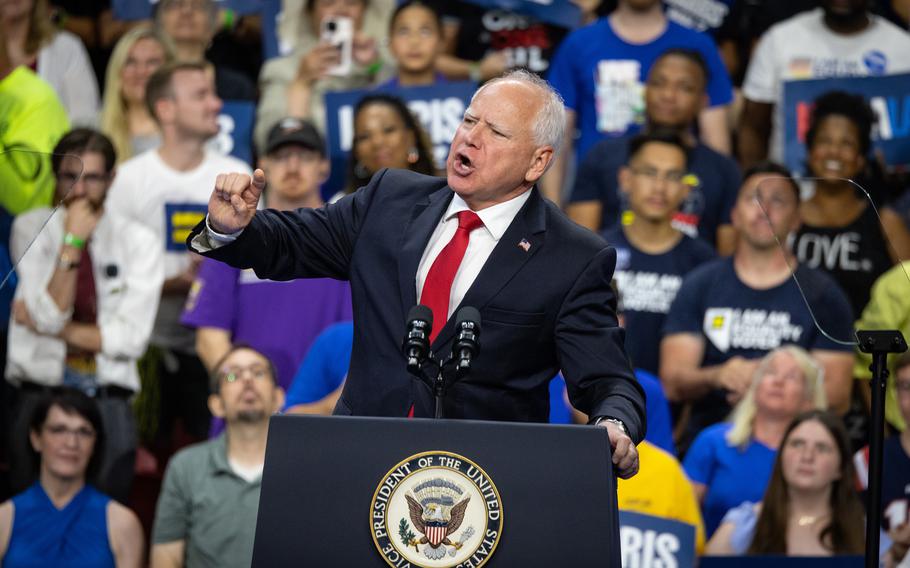

Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz at a campaign rally in Las Vegas on Saturday, Aug. 10, 2024. Former President Donald Trump and his allies are continuing their attacks on Walz’s account of his military service. (Jason Armond, Los Angeles Times/TNS)

In a speech at the Democratic National Convention accepting the party’s nomination as vice president last week, Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz talked about his life before politics. He mentioned how his father died of lung cancer.

“Thank God for Social Security Survivor benefits,” Walz said. In fact, Walz has often talked about how the program helped stabilize his family in those days, allowing them to “live with dignity” rather than poverty. He talked about it when he ran for governor in 2018 and on the campaign trail with current Vice President Kamala Harris.

Walz is the exact kind of politician Social Security needs at the moment. Although Social Security, which along with Medicare is one of the country’s two largest entitlement programs, isn’t an issue in the 2024 elections, it’s likely to become regardless as lawmakers turn their attention from the race for the White House back to debt and deficits.

The Heritage Foundation, a conservative group spearheading an extensive plan to reshape the U.S. government called Project 2025, has long proposed making Social Security a voluntary savings program that workers can opt out of, in effect privatizing the program. Critics such as Heritage claim the program has long been a bad deal, arguing that workers would be better off in the long run investing the 6.2% of their earnings that go into Social Security on their own.

Walz’s story, however, makes clear that such reasoning is faulty. Social Security isn’t a retirement program, but an insurance program, and the return is protection, not dollars.

To be fair, most peoples’ understanding of Social Security isn’t wrong as much as it’s incomplete. When workers contribute 6.2% of earnings up to the tax cap, they are earning Social Security coverage for themselves when they retire. From this lens, Social Security is akin to forced savings with guaranteed returns. Yet, a quarter of Social Security beneficiaries are not retirees. (Some retirees have benefits levels based on their own earnings and others on the earnings of their spouse. Whatever wage history is used to calculate the benefit, those beneficiaries are still retirees.) That 6.2% tax contribution also earns coverage of their spouse and dependent children, and not just in the case of their retirement but also their disability or death.

Walz himself didn’t receive Social Security, as he was 19 when his father died, but his mother and younger brother did. There are 5.8 million survivors insurance beneficiaries like them today. His description of Social Security being the backstop between his family and poverty is supported by data. The Census Bureau estimates that the income from Social Security lifts 1.3 million children and 7.5 million non-elderly adults out of poverty. For comparison, that’s similar to the 1.4 million children kept out of poverty by the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, also known as food stamps.

It’s not surprising that Americans don’t consider the non-retiree part of Social Security’s coverage. Few expect to die or become disabled before they retire. The last two decades have unfortunately shown just how widespread that risk can be with two mass mortality events: The rising wave of opioid-related overdoses and the million plus Americans who died from COVID-19. The latter was also a mass disability event, though the estimate of the number affected is less clear.

There are also the “shadow” child beneficiaries of Social Security. About 10% of American children live with a grandparent, and 3%, or 2.3 million, were being raised by a grandparent as of 2021, according to the Labor Department. These children can only qualify to receive Social Security benefits as dependents if they are officially adopted by their grandparents. Otherwise, they simply live in a household in which Social Security is a large source of income.

Tim Walz is pretty old to be a posterchild for Social Security Survivor Benefits, but his story speaks for the millions of parents and their children who have found themselves in the unfortunate situation of having to draw on the program but fortunate that it’s there when needed.

That’s a protection more Americans ought to understand. And although we may be a decade or so away from when the Social Security trust fund used to cover benefits is estimated to fall short of tax revenues, whatever Americans fail to understand they’ll fail to defend.

Kathryn Anne Edwards is a labor economist and independent policy consultant. This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.