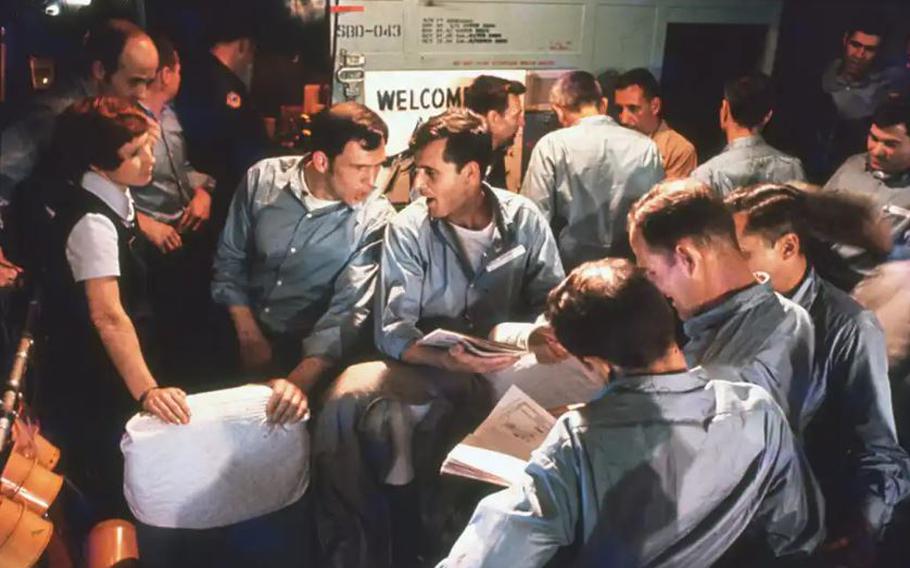

Former POWs talk during their flight from Hanoi to Clark Air Force Base on Feb. 12, 1973. (U.S. Air Force)

This Friday, March 29, marks the 51st anniversary of the completion of Operation Homecoming, which began on Feb. 12, 1973. It resulted in the return of 591 American POWs held by North Vietnam, the Viet Cong, the Pathet Lao and the People’s Republic of China. The longest held were first to fly back with Capt. Floyd James Thompson earning the dubious honor of first captured, first to return, spending almost nine years in captivity.

All the POWs had displayed incredible courage, undergoing torture by their Vietnamese captors seeking to break them any way they could. Under military regulations, a fine line existed between what POWs could and could not say. Knowing the Vietnamese lacked the resources to verify what the POWs revealed just to stop the beatings, many told wild tales. Although it might take months or even years to verify those tales, when found to be untruthful, POWs were subjected to even more intense rounds of beatings.

Many POWs were kept in the living hell of solitary confinement. So much about survival involved relying upon each other, even in such solitude. They developed a tap code system consisting of a varied number of knocks to communicate with each other through their cell walls that was never discovered by their Vietnamese captors. It was one way to learn from the more recent POW arrivals how the war was going — although that news was not always encouraging. Their jailors did a pretty good job of making sure any news of a negative nature occurring back home was immediately shared with the POWs.

One prisoner held 8½ years was Everett Alvarez Jr. Married just a few months before being shot down over North Vietnam, the one thing that kept him motivated was returning to his bride. However, after several years in prison, his captors learned Alvarez’s wife had divorced him and remarried. Alvarez was shown the news story in hopes it would break him. It failed to do so. However, while the news was devastating, his compassion was evidenced by his hope the man his now ex-wife had married would love her as much as he did.

Alvarez survived, returning to the U.S. He soon learned fate would bring him happiness again with a beautiful young bride. In Washington, D.C., Alvarez had given a press conference. Aware of his visit and that he would be flying out of Dulles Airport, United Airlines sought to give him the VIP treatment, sending a representative, Tammy Ilyas, to escort him to his flight. Tammy was immediately impressed with Alvarez — taken aback by his low-key and very unassuming nature. It led to a quick courtship and marriage. The best man at the wedding, as well as most of the ushers, were former POWs, all of whom considered Alvarez a role model POW they attempted to emulate in captivity.

In addition to their courage, a trait these POWs seem to share in common was the desire, even after leaving military service, to continue serving their country and an unending thirst for knowledge.

Alvarez went on to earn degrees from Navy Postgraduate School, George Washington Law School, two honorary doctorate degrees, chair the Board of Regents at the University of Health Sciences, etc. before going on to serve as the deputy director of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Another POW, Orson Swindle, a highly decorated Marine pilot who spent six years and four months in captivity, unfortunately had been shot down on his 205th combat mission — which was to be his last. However, he returned home to help others by directing financial assistance programs to economically distressed rural and municipal areas of the country under President Ronald Reagan. He also served as commissioner of the Federal Trade Commission.

For men like Alvarez and Swindle, hardship only spawned later success serving others.

One of the tragic stories of Operation Homecoming was Air Force Capt. Alan Brudno, who returned after 7½ years as a POW, also on the first flight home. A newlywed when he had been shot down, Brudno spent his captivity “writing” a remarkable poem about his wife. But what made it remarkable was that, since his VIetnamese handlers would not allow him any writing devices, he had to memorize the poem, which was epic in nature. Immediately upon boarding his Operation Homecoming flight, he asked the flight attendant for a tape recorder to transcribe the poem. It took him 45 minutes to recite!

After four months back home and apparently victimized by depression and the flood of anti-war fervor he heard, Brudno sadly took his own life — just one day before his 33rd birthday. His death was an indication that not all wounds of war were visible.

Brudno’s death was a learning point for the Department of Defense. It caused a review of how returning warriors were treated and evaluated as well as integrated back into society. All POWs were immediately called in for consultation and evaluation.

It is hard to believe but initially Brudno’s name would not be added to those on the Vietnam Memorial Wall, as his death did not occur in combat in Vietnam. A concerted effort by his family, friends and fellow POWs like Alvarez and Swindle, arguing that while he died in the U.S. he had “endured long term, severe physical and psychological abuse and torture-related wounds,” suffered in Vietnam, ultimately claiming his life here, finally won out. In 2005, his name was added to The Wall.

Brudno had learned French during his captivity as a POW. When his body was discovered after his suicide, a two-line note, written in French, was found next to him. It read, “There is no reason for my existence ... my life is valueless.” It was a sad final commentary on the life of a courageous warrior who had endured so much pain and suffering on behalf of his country.

We are witnessing another tragedy from Operation Homecoming today. While the surviving POWs recognize the significance of March 29, our young students do not. Another anniversary will come and go with neither Brudno, nor any of the Vietnam war POWs, being recognized for their courage and sacrifice — the result of teachers prioritizing wokeism over remembering America’s true heroes.

James Zumwalt is a retired Marine infantry officer (lieutenant colonel) who served in the Vietnam War, Panama and Operation Desert Storm. He is the author of three books and hundreds of opinion pieces in online and print publications.