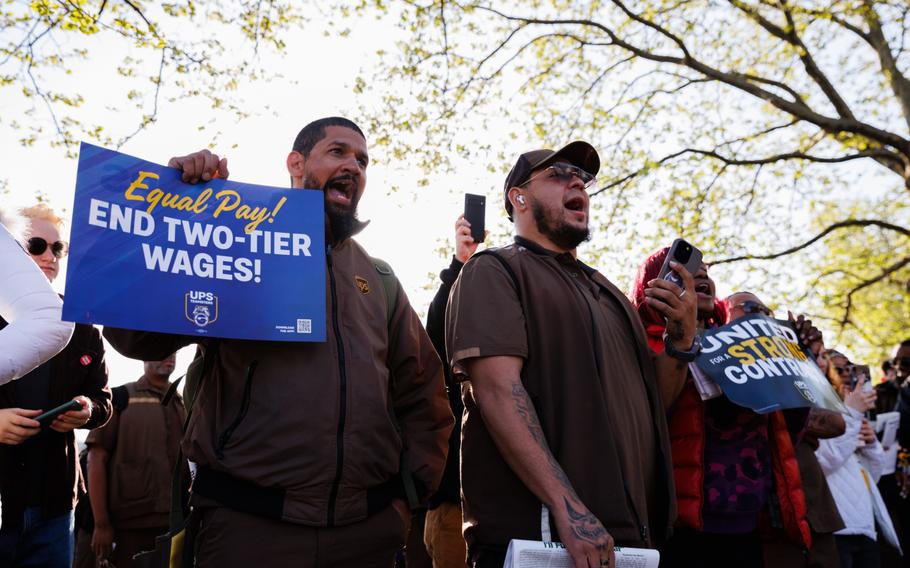

UPS workers and Teamsters members during a rally outside a UPS hub in Brooklyn in April. (Paul Frangipane/Bloomberg)

This is, you may have heard, the “summer of strikes.” The summer of threatened strikes, at least — more than half the 650,000 workers said to be on or headed for the picket lines in the U.S. were United Parcel Service employees whose union, the Teamsters, now has a tentative deal with the company. Another looming strike just fizzled for a less happy reason: Perennially struggling trucking company Yellow ceased operations this week before its 22,000 Teamsters-represented workers could walk out. Without those strikers, this year’s total seems unlikely to top 2018’s 485,200 or 2019’s 425,500 workers involved in stoppages of 1,000 workers or more, numbers that themselves were far below those of an average year in the 1950s, 1960s or 1970s, when the workforce was much smaller.

Still, the narrative underlying most “summer of strikes” media coverage — that private-sector unions in particular are feeling more confident and making more noise than they have in quite a while — is not incorrect. The strikers in 2018 and 2019 were mostly teachers and other state and local government employees, while this year most are employees of private companies. A lot of current private-sector organizing is on a location-by-location basis with strikes that don’t show up in the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics counts because they involve fewer than 1,000 workers, with the more inclusive Cornell-ILR Labor Action Tracker counting 224,000 workers involved in stoppages last year, nearly double the BLS tally of 120,600. The 340,000 workers who didn’t go on strike at UPS because the company gave in to their wage demands should probably count as a significant union victory even if doesn’t show up in the strike statistics. And according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ other main measure of strike activity, days on strike divided by total working time, this year may still prove a standout, at least by post-1980 standards.

That last significant spike, in 2000, was caused mainly by 135,000 members of the Screen Actors Guild and the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (which have since merged) striking for five months. SAG-AFTRA’s 160,000 current members walked out again on July 13, joining 11,500 members of the Writers Guild of America who went on strike in May, and as Lucas Shaw describes in the latest Bloomberg Businessweek, the issues at stake may not lend themselves to quick resolution. The United Auto Workers union also emphasized its preparedness to go on strike and stay out for a while as it entered contract negotiations last month on behalf of 150,000 hourly employees of the Big Three Detroit automakers.(1)

These standoffs are both unique. The UAW is one of the last big industrial unions; Hollywood is one of the only high-paying creative/professional sectors that’s unionized. Only 6% of U.S. private-sector workers belonged to a union in 2022, the lowest percentage on record going back to 1900.(2)

As already noted, much of the union action at the moment is at too small a scale to show up in the official strike statistics. Unions are trying to organize private-sector service workers and having to do it warehouse by warehouse and store by store. The Cornell-ILR tracker is full of evidence of this activity: 17 workers striking for a day at a Starbucks in Tucson, Ariz., four for three days at a Papa John’s in Southern California, 60 for half a day at a suburban Detroit Amazon warehouse. It’s a fascinating portrait of labor relations in ferment, and after a pandemic, a “Great Resignation” and big wage gains for lower-paid workers, who knows where we’re headed. But until the private-sector unionization percentage stops falling, it seems way too early to paint it as a union resurgence.

---

(1) In case you were wondering, the big spike in 1959 was due mainly to 519,000 steelworkers going on strike for 116 days.

(2) The pre-1983 statistics in the chart are from labor economist Richard Freeman’s 1997 National Bureau of Economic Research working paper “Spurts in Union Growth: Defining Moments and Social Processes,” and from Leo Troy and Neil Sheflin’s 1985 Union Sourcebook, which I did not actually hold in my hands (it would have taken a couple of days to get from the library’s off-site storage) but took economic consultant Wendell Cox’s word for what it said about private-sector union membership.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist and author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.” This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.