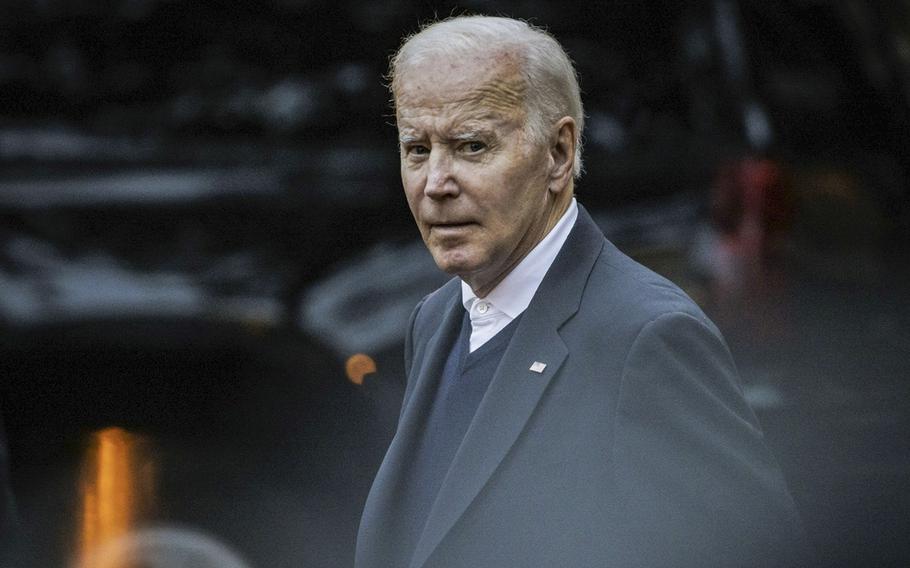

President Joe Biden in Washington, D.C., on Oct. 1, 2022. (Samuel Corum/Bloomberg)

President Joe Biden has a choice to make about the next two years, and it boils down to this: What’s more important, being a successful president, or leading his party to victory? Sadly for the country, these goals can’t be easily combined.

In his State of the Union address last week, Biden showed that he has chosen campaigning over governing. He didn’t invite Republicans to join forces on points of agreement and seek incremental progress where possible. Mainly, he set out to provoke and embarrass his opponents — and succeeded. Ritual calls for bipartisanship were issued, but they were transparently insincere.

The sad part is not just Biden’s choice — he is a politician, after all — but that his decision makes a certain kind of sense. U.S. politics is increasingly a contest between committed progressives and committed conservatives. I sit with much of the country — I’m guessing a plurality — in the moderate center, impressed with neither side and profoundly bored with the game. Neither party’s main goal is to appeal to this center. For what might be good tactical reasons, it’s more productive to enthuse your supporters and (which amounts to the same thing) enrage your critics.

Good government and pragmatic centrist compromise have much in common. The politically engaged have little appetite for either.

Biden’s stunt over the future of entitlements was emblematic. He said Republicans want to “sunset” Social Security. The suggestion that any Republicans, let alone most Republicans, want to shut down the program was a distortion that provoked, presumably as intended, derision and rebukes on the GOP side. Biden then maneuvered his braying opponents into an ovation: “Let’s stand up for seniors. Stand up and show them. We will not cut Social Security. We will not cut Medicare.” It was high-fives all round in the White House, apparently, as officials watched the president stick it to the enemy.

Thus did campaigning win out over governing. It so happens that the Social Security and Medicare programs are on track for technical insolvency — a readily solvable problem, by the way, provided it’s recognized and dealt with promptly. Back in 1983, in somewhat similar circumstances, Biden voted for Social Security amendments proposed by the Greenspan Commission, which balanced the books in part by gradually raising the retirement age. Some such solution, involving a combination of tax increases and expenditure cuts, will be required again. The sooner it’s undertaken, the less disruptive it will be.

Biden could have proposed a new commission to study the options for maintaining the programs. He judged it better to ignore the problem, entrench paralysis, and grin over the Republicans’ embarrassment.

The president also applauded his success in engineering several bipartisan agreements during his first two years — most notably, the $1 trillion infrastructure bill (which progressives held hostage for months before it was eventually passed). But he cast these measures less as genuinely joint accomplishments than as progressive victories over Republican skepticism and as down payments on more radical tax and spending programs he remains committed to.

“Finish the job,” he kept saying. What he appears to mean by this — an endless list of new spending commitments and rules to rein in rapacious private enterprise — is plainly incompatible with bipartisanship. That’s the point. He knows that legislation can’t deliver this agenda now that Republicans control the House. But if the political center can’t bring itself to take an interest, there’s political advantage in making absurd demands, being furiously rebuffed, and getting nothing done.

Democrats will ask: What’s the point of seeking compromise with today’s Republicans? A fair question. And the logic works the same for the other side. Neither party actually wants compromise, and both are delighted to accept the results for the way the country is, or isn’t, governed.

In the end, no doubt, we moderates are to blame. The politically engaged — progressives and conservatives alike — can justifiably tell disgusted centrists with no strong partisan attachments, don’t expect the government to work as you would like if you can’t be bothered to participate. That’s the problem in a nutshell. The center is disenfranchised, partly by its own lack of conviction. Its power subsides, the political temperature goes up, the quality of government goes down, and the cycle repeats.

Once upon a time, politicians such as Joe Biden did actually seek bipartisanship and were a countervailing force. Those days appear to be over.

Clive Crook is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist and member of the editorial board covering economics. Previously, he was deputy editor of the Economist and chief Washington commentator for the Financial Times. This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.