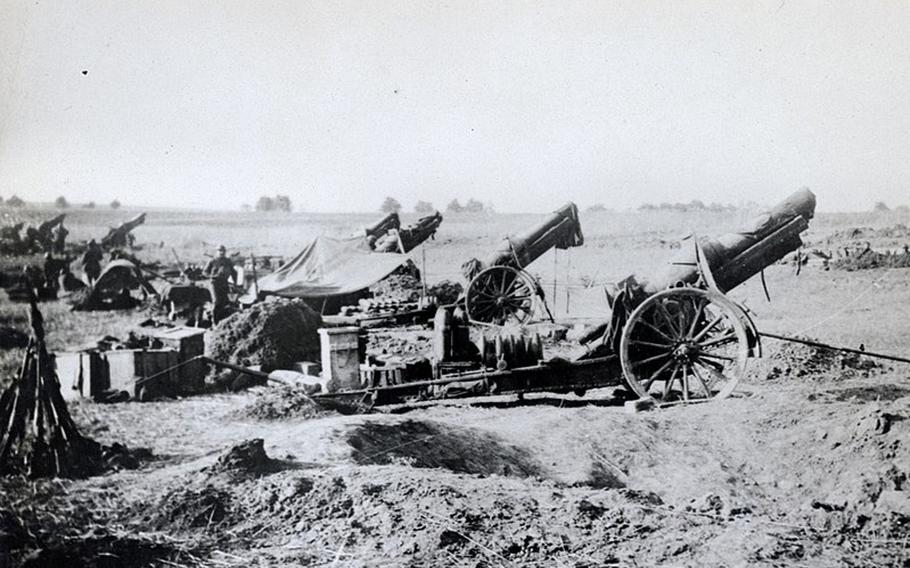

American heavy artillery at Soissons, France, 1918. The Battle of Soissons, the centerpiece of the Aisne-Marne offensives of July 1918, might be considered a decisive moment in the last phase of World War I. (NationalArchives at College Park - Archives II College Park, Md. )

On July 15, 1918, Germany’s military commander Erich Ludendorff unleashed what he optimistically called his “Freedom Offensive.”

It was his fifth — and as it would prove final — offensive of that spring and summer, although not for the reasons he had hoped. No final German breakthrough was achieved. Instead, it would prove to be the last throw of the dice which turned the tide against his own forces in World War I. In November of that year, Germany would sue for peace.

Intent on drawing Allied reserves into the area from northern France and Belgium, Ludendorff sent his troops cascading around the city of Reims in the Champagne sector toward the Marne River — a resumption of the Aisne-Marne assault of May and June when he had originally hoped to break the back of the Allies.

Within hours, his troops had crossed the Marne — one of the key gateways to Paris — east of the bridgehead of Chateau Thierry.

In their way stood the American Expeditionary Force’s 3rd Division, a constituent part of the French 5th Army. At its core were two AEF regiments whose stout defense would later lead them to be dubbed the Rock of the Marne: Ulysses Grant McAlexander’s 38th Infantry and the 30th Infantry headed by Col. ‘Billy’ Butts. The two regiments repelled the attackers across the valley of the Surmelin River running into the Marne.

With the German offensive now effectively stalled, Allied Supreme Commander Marshal Ferdinand Foch could focus his full attention on the counteroffensive that he was planning some 20 miles further north.

Foch had picked the area south of the strategic transport hub of Soissons to turn the tide on the Germans and bite into the bulge of a salient created in the Aisne-Marne area by the German assaults of May and June. His aim: to attempt to push enemy forces back beyond the Vesle and Aisne rivers from where they had begun their attacks two months before; offensives which for a period threatened Paris itself.

Accordingly, Foch directed that key units be gathered up in the Villers-Cotterets forest southwest of Soissons, as part of the French 10th Army. Key to the operation, was the army’s XX Corps, which was to spearhead the assault, comprised on either flank by the U.S. 1st and 2nd Divisions, with the doughty 1st Moroccan Division at its center, which included a polyglot mix of Foreign Legionnaires.

It was from there, as dawn broke on July 18, that the attack jumped off.

Advancing from west to east behind a rolling barrage of medium and heavy artillery, the three divisions focused on the area south of Soissons, aiming to sever the strategically important road and rail links from Soissons down to the Marne.

The attack succeeded in penetrating German lines by 2-4 miles. The regiments of the 1st Division’s 2nd Brigade on the northernmost flank sustained particularly heavy incoming fire as they attempted to pass over the Missy Ravine; and some 1,500 total casualties were reported.

It was a figure set to double the following day, as the defending enemy forces dug in and as the Allied units were afforded less support from the tank battalions which had accompanied them into battle.

But still the AEF divisions maintained their momentum. The 2nd Division, attacking the southern sector, made impressive and rapid movement in the face of rising casualty toll. Seven miles of ground was gained in just over 24 hours. By July 21, they had driven well beyond the road leading from Soissons down to Chateau-Thierry on the Marne, as German divisions began withdrawing from the salient.

No one immediate endpoint to the Americans’ Soissons campaign can be easily identified or a single moment of victory declared. It was not all over in an instant. The German presence did not disappear entirely in the weeks ahead.

Yet the speed and aggression of the AEF units marked a signal military achievement. For the first time in 1918, Ludendorff’s men found themselves on the retreat and no further offensive was to be attempted by them in the remaining 3 1/2 months of the war.

These were still early days for the AEF in the conflict. The first full US-led assault had only taken place two months previously at Cantigny in northern France.

That had been followed by the fighting in around the Marne, including the Marines’ bloody Battle of Belleau Wood. Battle order was still being learned and mistakes made. Heavy casualties had been sustained in all the conflicts to date: a mix of poor planning; insufficient artillery support and communications with that artillery; and problems relating to transport and supply.

But what was not in doubt was the Americans’ steadfastness on the battlefield. The troops’ willingness to fight had been tested in often treacherous conditions and they had proved themselves to be up for the fight.

“It is not often possible to say of wars just when and where the scales wavered, hung, then turned for good and all,” said Gen. Robert Lee Bullard of the Battle of Soissons, as he singled out the work of his divisions in the fight.

It was a sentiment echoed by Word War II Army Chief of Staff Gen. George C. Marshall, who, as an operational strategist, came of age with the AEF in World War I:

“The entire aspect of the war had changed. The great counteroffensive on July 18 at Soissons had swung the tide of battle in favour of the Allies, and the profound depression which had been accumulating (was dissipated) and replaced by a wild enthusiasm throughout France and especially directed towards the American troops who had so unexpectedly assumed the leading role in the Marne operation.”

Patrick Gregory is co-author with Elizabeth Nurser of “An American on the Western Front: The First World War Letters of Arthur Clifford Kimber 1917-18.”

Twitter: @americanonthewf