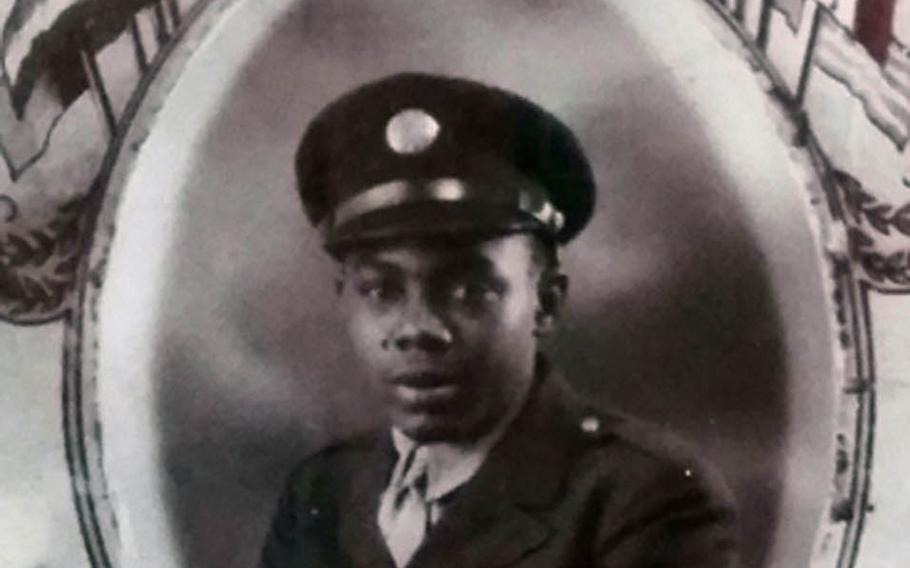

Army Pvt. Mack Homer was killed in an explosion in Normandy, France, on July 7, 1944, one month after the D-Day invasion. (Courtesy of Barbara Foulkes)

On July 7, 1944, a month after the Allied invasion of Normandy, soldiers from the 364th Engineer General Service Regiment entered a captured German emplacement that was stocked with munitions — most likely to disarm or dispose of them.

What happened next is unknown, but there was an explosion that claimed the lives of seven men.

A few of the combat engineers were identified in the aftermath of the blast; Pvt. 1st Class Sylvester Haggins, Pvt. Mack Homer, Pvt. Henry Simmons and Technician Fifth Grade Daniel Wyatt were not.

Fast-forward 72 years, and the men have been reduced to names on a register, their loved ones long since buried with their memories and the pain of their losses.

However, thanks to a new tool developed by Kenneth Breaux and his team at M.I.A. Recovery Network, a nonprofit that advocates for missing-in-action servicemembers and their families, there is a renewed sense of hope that at least one of the men could soon be identified.

Breaux — a retired Navy officer with experience in data analysis — and his team have developed a database of unknown World War II-era U.S. soldiers buried in American cemeteries. After plotting the Military Grid Reference System location of each recovered unknown from the European theater and entering details — service branch, last-seen location, date of death, height and dental work — the team can search unit records for matches.

The tool is not foolproof — World War II records are spotty at best — but several cases have jumped out right away, showing that the system can aid researchers in making identifications.

One of the first was the case of Normandy’s X-27.

“While doing the data structure, we began to notice clusters of similar information,” Breaux said. “This is what led us to the possibility of the ability to mine those data clusters for information that could lead to identification. The clustered data provides a narrowing of possibilities for identification.”

If an unknown was recovered in a certain area, at a certain time, and if the team knows which units were in the area and who was lost, the database can look for similarities to whittle down the list of potential matches, Breaux said.

Unit records and Individual Deceased Personnel Files, which often say where missing men were last seen, can also be used to fill in gaps.

“Of course, all of this, in the end, will depend on DNA analysis in most cases, but the ability of our data mining should narrow the possibilities so that if we know that four men of the 364th General Engineering Service Regiment died in an area, and we can get DNA from one or more of these men’s relatives, our chances for identification increases,” Breaux said. “We need this also to make the case to disinter” to the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency.

‘Courtesies of the Heart’ The database was born over a decade ago. A woman who lived on Breaux’s street told him she never knew what happened to her father, Army Air Corps Lt. William Lewis, who was lost over Germany in 1944.

Breaux began to investigate and eventually went to Europe where he found and helped recover Lewis’ remains. He wrote a book about the experience titled “Courtesies of the Heart.”

Breaux began receiving letters and requests for assistance from families across the United States. The M.I.A. Recovery Network was born.

As Breaux helped families and pored over government documents, he said he starting seeing correlations. As he worked with other researchers through his nonprofit, an Army officer named Robert Rumsby showed him a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet of data. Breaux suggested they take it to the next level. They entered the data from every file accompanying unknown remains, called an x-file, that they could get their hands on, putting in thousands of man hours. Then they began to compare them with mapped coordinates and events, like specific battles. These efforts are starting to bear fruit.

“We have a database built from archival material in the x-files and now we have a map that you can access that shows the physical location of every single recovery in Europe,” Breaux said. “When you go through the files and extract the data from the x-file and you put it into the data sheet, it becomes much easier to say, ‘OK, now I’ve got a relationship, now I’ve got an aggregation of data, now I can begin a pursuit,’ and some of these are pretty straightforward — not all of these — but a lot of them are pretty easy to figure out.”

Breaux and his team saw clusters of unknown dead in Normandy. They began to look at the units operating in the cluster areas at the time and who they had lost.

They saw that four were still missing from the 364th Engineer General Service Regiment — Haggins, Homer, Simmons and Wyatt. The x-file for Normandy X-27, an unknown recovered in the area of their deaths, confirmed their suspicions. One of their officers, Lt. Roy Diddle, had written a note that the remains belonged to one of the four men killed in Fontenay-sur-Mer, near Utah Beach, on July 7, 1944.

The officer could not identify the remains because they were missing a skull and hands and had multiple fractures. The note was not found in any of the other files.

Breaux’s teammate Jana Churchwell located relatives for two of the men, the bar that must be met for disinterment, and has instructed the families on how to contact the U.S. Army’s Past Conflict Repatriations Branch to submit DNA for testing. In an interview with Stars and Stripes, Barbara Foulkes, Homer’s niece, indicated that their family would follow through.

When she got the call, “I couldn’t believe it,” Foulkes, 80, said. “I certainly will pursue it.”

Foulkes said Homer was the ninth of 15 children. Her father was the oldest and was very bitter about his younger brother’s death. Homer was last seen boarding a train as he headed off to basic training. It was a sad memory that has been passed down through the years.

“My father didn’t talk much about Uncle Mack,” Foulkes said. “Mack was young [only 20 at the time of his death] and he wanted to get out of Georgia and get a better life, and joining the Army was one of the best answers, but unfortunately ...”

She grew quiet as she searched for words.

Breaux said that even if Homer’s family does submit DNA, there is no assurance that DPAA will disinter the remains in Normandy for DNA testing. He showed Stars and Stripes several other cases where unknowns were narrowed down significantly to prove the validity of his system under the condition that Stars and Stripes not report on those. Breaux said they were not finished with their investigations.

Long-term vision “The vision that we have, now that we have this data in an orderly fashion, is that we can create data sets that people can feed into,” Breaux said. “That’s the next step. Our long-term vision includes much more rigorous archival research such as linking recovery of remains to Army Morning Reports, After Action Reports, Missing Air Crew Reports, etc.”

Breaux said funding would be needed to obtain and add even more records to the system. He said DPAA had expressed interest in working with him on this system after he submitted a proposal in late 2016; however, no offer to join forces was made. He has since found out that DPAA is building its own database system. DPAA officials confirmed to Stars and Stripes that Na Alii Consulting Sales LLC in Honolulu had been awarded a nearly $20 million contract to build a database and information system. That work is supposed to be completed by 2020.

“We believe an integrated information system will be critically important to our mission,” DPAA spokeswoman Maj. Natasha Waggoner wrote to Stars and Stripes. “We anticipate it will greatly support our desire to better collaborate, reduce data redundancy, and we hope to incorporate some new technology that enables us to better manage our data.”

She said the agency hopes to share some information with families and the public, but they are limited by Defense Department rules on classification and privacy. She said that is why it was important to have classified and unclassified databases.

Waggoner encouraged Breaux and his team to continue trying to work with DPAA.

“We are committed to securely governing our data, and where we can we will enable direct sharing for as much of the data as possible to leverage the public and partners insight and capabilities,” she wrote. “DPAA recognizes the interest, enthusiasm and expertise of many members of the public for our mission. We remain committed to building effective partnerships and maximizing the DoD ongoing efforts to account for the missing.”

Breaux said that if he doesn’t partner with DPAA, he will open his database to MIA families and researchers. Successful MIA investigator and founder of the nonprofit PFC Lawrence Gordon Foundation Jed Henry said he hasn’t used Breaux’s system but that it could be useful.

“I would certainly like to get my hands on it and see how helpful it might be,” Henry said. “The unfortunate part is that WWII records are fragmented and incomplete. They rarely tell the whole story so you are often left with [just] theories.”

Henry said there are other concerns, such as being able to search without tipping off others to the cases he is working on, and whether there would be an online database or files or analysis for each request.

Henry said he still believes in the systematic disinterment and DNA testing of all unknown soldiers as the best way to identify them. However, until that happens, databases like Breaux’s could fill in some of the gaps.