News

Navy helps coastal Africa map a common picture of the sea

Stars and Stripes May 15, 2014

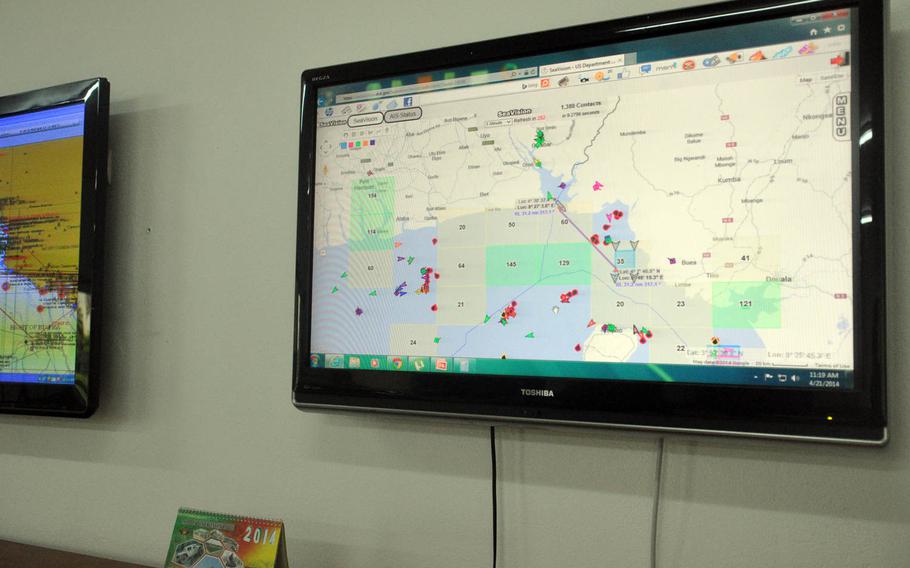

A monitor inside a maritime operations center in Idenau, Cameroon, shows the interface for SeaVision, a Web-based maritime monitoring tool developed by the U.S. Department of Transportation and used by African countries for a common picture of marine traffic and threats. (Steven Beardsley/Stars and Stripes)

IDENAU, Cameroon — Kirsty McLean doesn’t need to look out from the shore of this small fishing village to spot one of coastal Africa’s lingering problems. She can just log on to her computer.

Using a Web-based mapping tool that plots nearby ships through their VHF (very high frequency) transponders, McLean recently layered another view on top, this one from a satellite searching for ship-size objects in the area. Dozens of new markers suddenly appeared on the screen — a full fleet of ships otherwise unnoticed in territorial waters.

“This is telling you you have a problem,” she said.

Armed robbery, illegal fishing and drug trafficking are major issues facing Gulf of Guinea nations such as Cameroon. They are also concerns for the U.S. military, which has funded or financed new coastal radar sites in several countries.

Getting those nations to share that information is the job of McLean, a Navy civilian. Her online mapping tool, which is improving with the increasing availability of satellite imagery and expanded coastal radar, has become more attractive since a recent agreement by Gulf nations to share more of their data.

“You need to be able to see what’s going on out there in order to respond to it,” said Bryon Smith, director of Africa engagement for U.S. Naval Forces Europe-Africa, where McLean works.

Nine nations share waters along the Gulf’s most active stretch, from Ivory Coast to Gabon, creating a patchwork of surveillance systems and a host of technical and political issues with sharing data. Many nations have gaps in their radar coverage.

The dishes also have their limitations as surveillance tools. They are good for line-of-sight detection 20 to 30 miles out — enough to cover territorial waters — but well shy of the 230-mile exclusive economic zone, a region where countries protect their own fish and resource stocks.

Until recently, the lack of a common radar picture left Gulf nations with few resources for sharing information on suspicious vessels, a problem more pronounced among poorer nations unable to afford much coastal radar coverage.

McLean, who works alongside Navy trainers in Africa, was looking for a way to develop that common picture when she spoke to a representative of the Volpe Center, a Department of Transportation initiative that creates transportation-related projects for federal agencies. The representative said he might have something in mind — the center had once worked on a similar concept for U.S. Southern Command.

Programmers pulled that project from the shelf, modified it and in 2010 released SeaVision, a Web-based vessel tracking system that uses ships’ transponders to draw a real-time picture of marine traffic on a common, unclassified interface. Based on Google Maps, the program takes data from the Automatic Identification System, the transponder signal system required of all flagged merchant vessels, and uses it to map ships in real time. Users can track vessels, look at their steaming histories and correspond with other SeaVision users to highlight particular vessels or pass along information.

The AIS data comes via participating countries, who agree to plug their receivers into the program. Satellite AIS receivers ensure vessels can be tracked farther out from coastlines.

The Naval command for Africa began disseminating SeaVision in 2011 through its exercises with African forces, and McLean encouraged countries to continue using the program in their regular surveillance.

“We didn’t want to do something that they just used doing exercise because we wanted to build a capability that was consistent — it was there whether we were there or not,” she said.

A year after the program’s introduction, 20 countries were using SeaVision, McLean said. Administrators can track logins, allowing them to see which users appear comfortable with the program and which may need more training or might be having technical issues. The Navy still provides many of the accounts, she said.

AIS alone can’t provide a complete picture of a nation’s territorial waters or the exclusive economic zone. Merchant ships can turn the system off, and smaller boats may not even have it. McLean estimates well over half the vessels in the Gulf of Guinea are operating without AIS.

She believes new data feeds will help clear the picture.

The new European Union satellite program Sentinel-1 is expected to provide African nations free satellite images beginning later this year, she said. Although the satellite passes will be irregular — perhaps once every few days — the images will show how many ships are not using their transponders. Coastal radar, which some countries are feeding into the system, can provide similar information. As the U.S. military continues to update radar towers and add new ones, the information should become even better.

Countries should use the new data to enforce AIS requirements, and as a general indicator of where ships are clustering, McLean said.

“It’s telling you about a problem,” she said. “You can tell the patterns of life. OK, well there was this many ships there last week. Is there this many ships there this week? What fish is in season?”

SeaVision should also receive a boost with last summer’s Code of Conduct signed by West and Central African nations in Cameroon. The agreement, which followed a period of escalating armed robberies in the Gulf, calls for better information sharing among signatories and a new regional information-sharing center in Cameroon.

Here in Idenau, forces from Cameroon and Nigeria recently tested the new agreement with combined exercises aimed at boarding a suspicious vessel. McLean was on hand as a combined maritime operations center first detected the vessel, played by a U.S. ship, tracked it and then guided a boarding team of combined Cameroonian-Nigerian forces toward it.

Such skills can lead to real-world successes, McLean thinks. She sees validation in a January interdiction off the coast of Senegal, when maritime officers there acted on a tip to board a Russian-flagged vessel thought to be fishing illegally.

McLean said the Navy helped Senegalese forces by looking at the ship’s history on SeaVision and tracking its movements. The country extracted a $1.2 million fine from the owners of the ship, the Oleg Naydyonov, which was a repeat offender.

Further improvements to coastal surveillance across Africa, often called maritime domain awareness by the military, will remain a cornerstone of the Navy’s work with African nations as long as maritime crime threatens global trade, oil prices and inland stability, said Smith, the official with U.S. Naval Forces Europe-Africa. SeaVision is an improving tool, he said — and a reality check on the seriousness of the situation.

He recalled one government minister’s reaction when shown a satellite feed on SeaVision.

“We turned this thing on and he’s like, ‘Well, what are all those ships out there, because we don’t see them out here?’ ”

The response: “That’s a good question.”

beardsley.steven@stripes.com Twitter: @sjbeardsley