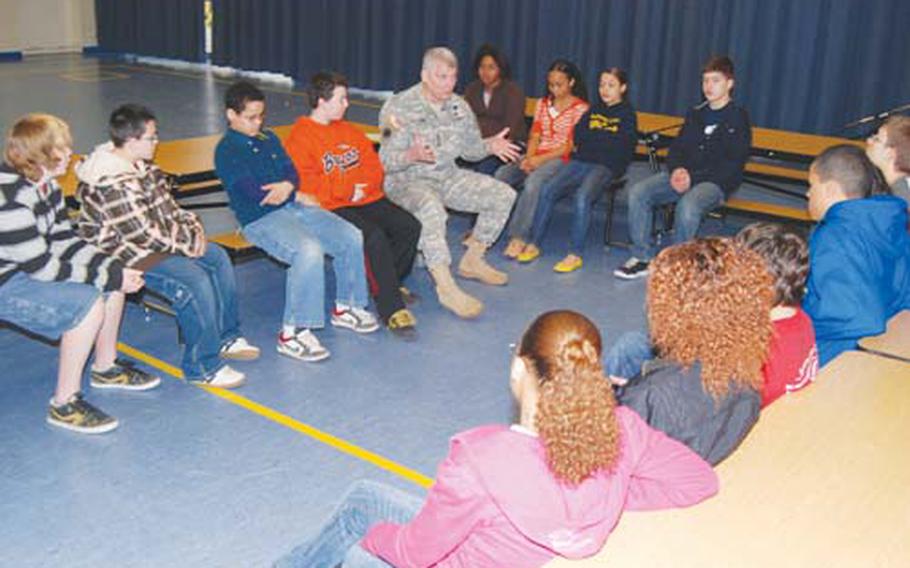

Gen. Carter F. Ham, U.S. Army Europe commanding general, talks with Heidelberg Middle School students about their concerns during an informal meeting in the school’s multipurpose room in February. The Europe Regional Medical Command will place mental health counselors in two DODDS’ communities next year to help students cope with their parents’ deployments. (Dave Melancon / U.S. Army)

BAMBERG, Germany — The Army will place mental health counselors in two Defense Department school communities in Germany in the coming academic year to test a new program aimed at combating the stress students face when their parents go to war.

With soldiers’ repeated deployments, children in military families have begun to experience mental health problems similar to those seen in their parents, according to Maj. David Cabrera, acting director for the Europe Regional Medical Command’s soldier family support services office.

Some of the common effects seen in children are anxiety, generalized fear, and academic problems that even go as far as regression to previous developmental stages.

Younger children have a more difficult time understanding why their mom or dad is gone during a deployment. The concept of war can be difficult — or even inappropriate with young children — for many parents to explain, he said. Older children have become depressed or aggressive, and struggled at school and in social situations.

In a 2008 DOD survey of 13,000 active-duty spouses, 60 percent of parents reported increased levels of fear or anxiety in their children, and 23 percent felt their children coped poorly or very poorly while a parent was deployed.

“Some [children] were having behavorial issues in school, and some were coping well with the deployments,” Barbara Thompson, director of the Pentagon’s Family Policy/Children and Youth office, said in a DOD release this week. “It’s very clear that spouses were concerned about the cumulative effects of deployments on their children.”

Since fighting began in Afghanistan, deployments have affected nearly 2 million military children, according the release. There are about 234,000 children who currently have at least one parent deployed, the release said.

One of those parents, Britta Vasquez, was recently reunited with her husband, Chief Warrant Officer 2 Humberto Vasquez, when he returned from a 15-month deployment in Iraq. Humberto Vasquez serves with the Headquarters and Headquarters Detachment 793rd Military Police Battalion out of Bamberg, Germany.

Britta Vasquez said it’s become harder for her children — son Bobby, 15, and daughter Natasha, 12 — to deal with deployments as they’ve gotten older.

“Now that they are teenagers, they are more aware of what is going on. ... They are no longer in their little family bubble,” she said. “There is more to their lives now with friends and school.”

She supports the idea of placing counselors in the school.

“It depends on the counselor [and] how well they connect with the kids,” she said. “It will not hurt having something like that available.”

In an effort to make it easier for kids in Europe to get the help they need, mental health workers will be hired for the Baumholder and Grafenwöhr/Vilseck community schools.

The communities were chosen for the one-year pilot program because of their troop and family density levels and their willingness to participate in the program, said Cabrera. Three of the Army’s four main combat units in Europe are located in those communities. The 172nd Infantry Brigade out of Grafenwöhr is currently deployed to Iraq.

Grafenwöhr/Vilseck is home to some 13,650 troops, 1,000 civilians and 1,000 family members, according to the Army. Baumholder hosts about 7,100 troops, 400 civilians and 400 family members.

The idea of bringing the counselors to the students was developed after Gen. Carter F. Ham, U.S. Army Europe commander, visited a group of Heidelberg Middle School students earlier this year to see how deployments affect them.

During the visit, the general asked the students if services at their school, churches or in the community helped them prepare for and deal with deployments. He also asked whom they rely upon during the “really bad days.”

“I want to make sure that you have the people and the services available to you if you want them,” Ham told the students, according to an Army news release. “I want to make sure you have folks that you can talk to, and that you can do so anonymously if you’d like to.”

Ham’s plans to provide mental health care for all Department of Defense Dependents Schools students led to the medical command creating the pilot program.

The program, part of the Family Support Services, allows children — with parental permission — to be seen by mental health practitioners at the school and eliminates the time spent to go to a clinic.

The pilot program is set to take place in “highly deployed areas.” Those deployments take a heavy toll on children, said Harvey Gerry, chief of education for DODDS-Europe.

Gerry said that DODDS students have proved “remarkably resilient” in the face of frequent relocations and their parents’ deployments.

“Deployments either single or repeated require children to adapt to unexpected changes and events in their lives,” Gerry said. “Extended separation can distract students from their studies, from the social interaction they typically enjoy in school and we want to be able to give whatever support we can.”

That support will hopefully be established by bringing counselors to the students.

The goal of the program is to offer direct care for known behavioral health issues as well as to provide educational and preventive programs that will speak to the stressors associated with deployment and reunion, Cabrera said. Referrals for care can come from a variety of sources to include: the principal, assistant principal, school counselor, teacher, student services coordinator, psychologist, social worker, behavioral health specialists or parent, said Cabrera.

“Children have a hard time knowing that mom or dad is gone and sometimes they have concerns,” Cabrera said. Kids might face the same difficulties as a soldier or a spouse would, “so it’s our duty and obligation to care for them just like we would an individual that brought up an issue,” he said.

Knowing their families are getting the help they need also should comfort soldiers downrange, he said.

Hiring of personnel for both areas is still taking place, but the program will be ready to kick off at the beginning of the 2009-2010 school year in late August.

The clinicians will be dedicated full-time to the schools, according to Cabrera, although some of them will rotate among the schools within the community. They will be available during school hours, but can also meet with parents when they pick up their child.

The first year is the validation year, Cabrera said. The intent is for it to expand across the European community, he said.