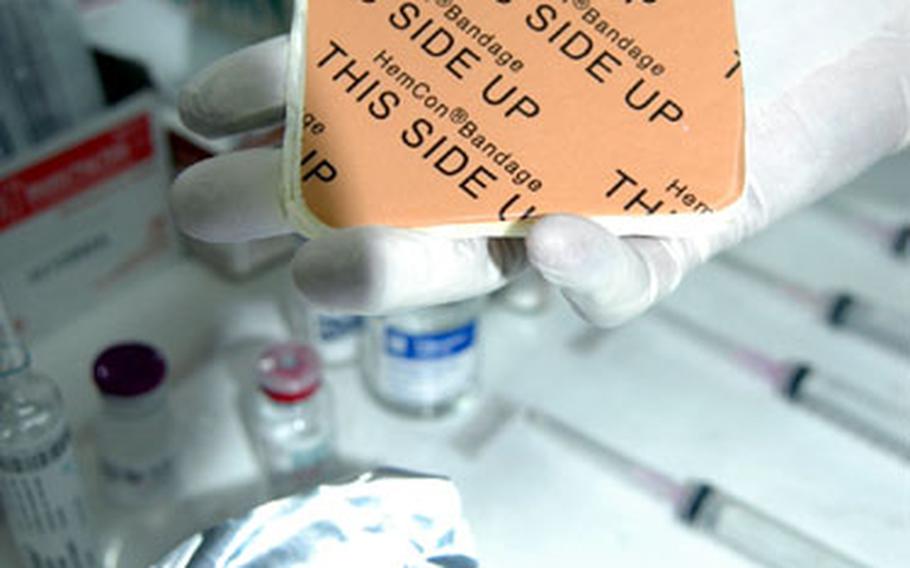

Hemcon bandages, which are used together with direct pressure or tourniquets to stop serious bleeding, are part of every soldier's combat medical kit. (Lisa Burgess / Stars and Stripes)

BAGHDAD — The “Hemcon” chitosan bandage in every deployed Army soldier’s combat medical kit is one of the wonders of the modern battlefield. It helps stop arterial bleeding in places where tourniquets aren’t totally effective, like the upper thigh, or if an arm is severed at the shoulder.

But some soldiers are using the Hemcons, which cost $120 each, the wrong way, according to medics and military doctors.

Some soldiers are plastering Hemcons on wounds where they can’t stick. And others are using them almost as casually as Band-Aids, according to Capt. Gerald W. Surrette, a doctor who is brigade surgeon of the 2nd Brigade Combat Team, 2nd Infantry Division.

The bandage’s cost isn’t the issue, Surrette said. It’s a matter of saving lives.

Fifty percent of all combat deaths, including those in Iraq, are caused by uncontrolled bleeding, according to statistics collected by the U.S. Army and provided by Surrette.

A large proportion of those deaths are immediate and unpreventable by anyone, including the most skilled surgeons in the world, Surrette said. But nine percent of troops who have died in Iraq have died from uncontrolled bleeding to arms or legs, he said.

“And those (kinds of deaths) are potentially preventable,” he noted. “We can do something about those, if every single Joe could be trained” to respond correctly on the battlefield.

In the effort to train and equip “every single Joe,” to save those lives, the best way to look at the Hemcon is “as another tool in your tool chest,” Surrette said.

Medically speaking, “there’s maybe one percent of the time” that the Hemcon bandage is the best possible option to use on a combat wound, he said.

“It’s way down the line of what you should reach for,” Surrette said. “The first thing you should reach for as you run to a patient should be your tourniquet.”

The Hemcon was developed by the Army’s Institute of Surgical Research at San Antonio, and named as one of the Army’s top 10 inventions in 2004.

The Army began to issue one Hemcom bandage to each deployed soldier just last year. There seems to be some confusion out there about how the bandages are supposed to be used, Surrette and his medics said.

Aid station medics and physicians at Forward Operating Base Loyalty in Baghdad have seen soldiers come in with Hemcons applied to wounds where direct pressure would have done a much better job controlling the bleeding. They’ve even been applied to relative scratches.

Then there are soldiers who look at the Hemcon’s thin, flat appearance and think it’s supposed to stick to skin and hold the edges of wounds together. That’s totally wrong, too, medics say.

On the other hand, military medics want to make sure soldiers don’t regard the Hemcons as some kind of quick fix that can simply be slapped on and solve all kinds of major combat trauma.

They shouldn’t be thought of as a cure-all, said Cpl. Heaven Gallop, 27, of Winston-Salem, N.C., a medic for the 2nd Infantry Division’s Headquarters Headquarters Company, 2nd Brigade Special Troops Battalion.

The Hemcon bandage is made from chitosan, a substance contained in shellfish shells. It works by reacting with blood and provoking a clotting reaction, which helps stop bleeding.

“But if there isn’t enough blood, the chitosan on the Hemcon bandage won’t have anything to react with,” said Spc. Mark Duchesneau, 33, of Boston, another FOB Loyalty medic with the 2nd Battalion, 17th Field Artillery. “It won’t work if all it’s in contact with is skin. You have to really force it in there.”

The bandages are flexible and can be rolled, bent or even cut if necessary to fit into slashes and cuts, he said.

Hemcons also can be very useful in helping to control bleeding in situations where a soldier has severed an artery high in the groin or very high under the armpit, for example, the medics said.

In those kinds of wounds, tourniquets can be difficult or impossible to apply, and direct pressure doesn’t always work because it’s hard to find the right spot to make the bleeding stop, Surrette said.

Hemcons can also help control abdominal bleeding, another place where a tourniquet can’t go.

Surrette said he has spent a lot of time training brigade soldiers on the proper use of the Hemcon bandage, and as a result, its casual use has dropped dramatically.

It’s important for soldiers to know what’s going to work best under fire, and that’s tourniquets and pressure, then a Hemcon bandage, Surrette said.

But “you do whatever you have to do to stop the bleeding,” he said. “I will never second-guess them. … I just tell them to keep the blood in, and get them to me.”

Using Hemcom bandages

Do:Use direct pressure or a tourniquet first. If that doesn’t work, go for the Hemcon, but keep using the pressure, too. Pressure and tourniquets save lives, medics say.

Use the Hemcon on full or partial amputations where a tourniquet is not controlling all the bleeding.

Use the Hemcon on major gashes to the torso, arms or legs where direct pressure isn’t controlling the bleeding.

Make sure the Hemcon is in contact with the source of the bleeding, not skin. Roll or stuff the bandage to fit into the wound if you have to. The clotting factor on the bandage needs blood to activate or it won’t work.

Make sure your hands are dry of blood (or water) before you try and apply the Hemcon, or it will stick to you, not the patient.

Hold the Hemcon in place, using pressure, for three to five minutes. Then wrap the Hemcon over the wound using an Israeli dressing, ACE bandage or other battle dressing.

Use more than one Hemcon if you think you need it to control a major bleed or cover the surface of a large wound. Just keep packing them in there.

Don’t:Don’t use Hemcons like Band-Aids. They don’t work on cuts and scratches because there isn’t enough blood.

Don’t reach for your Hemcon first. Hemcons help blood clot, but when it comes to stopping bleeding, they can’t replace direct pressure or tourniquets.

Don’t use Hemcons on open chest wounds.

Don’t use Hemcons on the head, especially the eyes and face.

Don’t try to take off a Hemcon — that’s a job for personnel at an aid station or combat hospital.

Don’t move a Hemcon around on a patient’s body. If it’s not sticking, use a fresh one.

Source: Capt. Gerald W. Surrette, a doctor with the 2nd Brigade Combat Team, 2nd Infantry Division.