A metal structure built on top of reconstructed ruins of Emperor Frederick I’s Imperial Palace is meant to give visitors an idea of how large the original building was. (Phillip Walter Wellman/Stars and Stripes)

At the Stadtmitte bus stop in downtown Kaiserslautern, people can usually be seen staring at their phones, flicking cigarette butts onto the pavement or gazing at the nearby shopping mall as they wait to be driven away.

Few would describe the area as picturesque. But hundreds of years ago, things were much different.

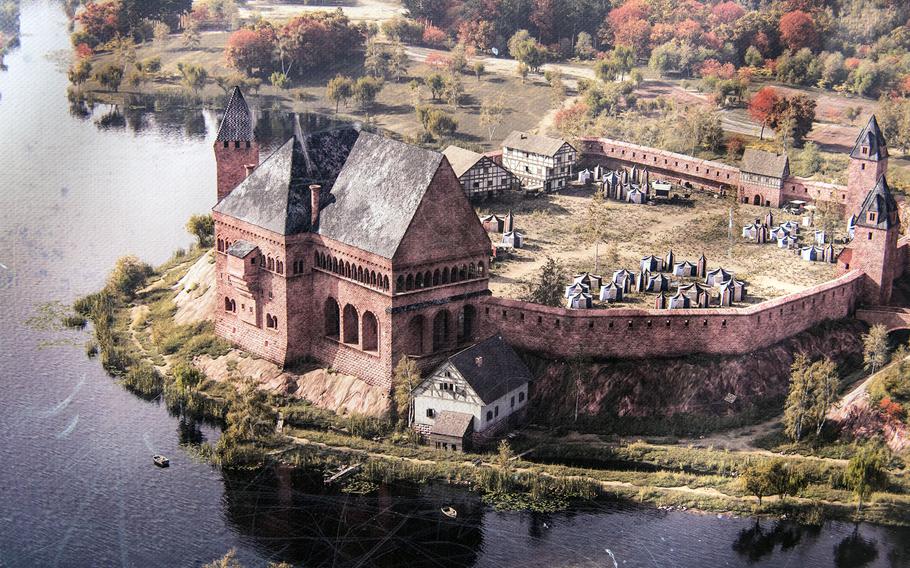

A river fed into a tranquil pond where the mall now stands, and perched on the shore was a large imperial palace, thought to be one of the most magnificent buildings of its kind in the Holy Roman Empire.

Today, ruins have been partially restored in a public space next to the bus stop, hinting at the area’s former grandeur. But markers at the site are scant, so people are unlikely to have any awareness of the exploration invitation in their midst.

An illustration of what Emperor Frederick Is Imperial Palace might have looked like is displayed in downtown Kaiserslautern on Saturday, Nov. 5, 2022, next to where the palace once stood. Today, the river and pond have been replaced by concrete streets and shops, and the palace has been partially reconstructed. (Phillip Walter Wellman/Stars and Stripes)

For anyone curious enough, though, the city offers public and private tours that take visitors around the grounds and through subterranean tunnels, where they can get an up-close look at history and even come face to face with an ancient skeleton.

Historians trace Kaiserslautern’s roots back some 1,300 years, and for much of that time, two buildings bore witness to its fortunes: the palace built by Emperor Frederick Barbarossa around 1152, and the Renaissance-style Casimir Castle, built by Prince Johann Casimir, which was completed around 1578.

The history of these two structures forms the basis of the tour, but only traces of them remain. In the 1930s, stones from the former Casimir Castle were used to construct a new building, the Count Palatine Hall, which still stands and is where the tour begins.

Tour guide Andrea Stephany takes English-speaking visitors through underground tunnels in central Kaiserslautern and explains the city’s history on Saturday, Nov. 5, 2022. (Phillip Walter Wellman/Stars and Stripes)

The hall is adorned with a large tapestry and wooden statues made around 1600, which are meant to give visitors a feeling of what life was like around the time the castle was built.

Following an introduction on the ground floor, the excursion descends into the underground tunnels via a stone spiral staircase. In total, the tunnels span about 80 yards and pass through several rooms equipped with illuminated display boards in German and sound effects that illustrate the history of the city. A tour guide explains everything in English.

A grave containing a Franconian skeleton, one of several unearthed during excavation work at the site in the 1930s, can be found in the first underground room.

The skeletons are said to have garnered the attention of Adolf Hitler, who ordered them to be transported to Mainz, about 50 miles away, to be studied for evidence supporting his discredited notions of Aryan supremacy.

A tour organized by the city of Kaiserslautern takes participants though several underground rooms, the first of which contains the grave of a Franconian skeleton. (Phillip Walter Wellman/Stars and Stripes)

However, the skeletons are said to have been forgotten in a basement in Mainz and were eventually returned to Kaiserslautern and buried in the city’s main cemetery, near Kleber Kaserne, where U.S. forces now work.

In the second underground room, visitors get a closer look at an original section of a stone wall that once encircled the area, even before the construction of Barbarossa’s imperial palace.

Over the centuries, successive masons fortified the existing wall by building onto it. So in the middle portion of it, stones more than a millennium old can be seen.

The underground wall is different from the one outside, which was rebuilt with historical stones and is not original.

After passing through another room that details how successive wars destroyed the area, the tour arrives at an escape tunnel. Such tunnels were used for fleeing or smuggling goods into the complex without enemies noticing.

Traversing through a narrow and damp escape tunnel is one of the highlights of an underground tunnel tour in central Kaiserslautern organized by the city. (Phillip Walter Wellman/Stars and Stripes)

The tunnel is believed to be the only one still in existence. Years of construction in the area destroyed the others.

The narrowness of the tunnel requires single-file movement through it. Claustrophobic visitors can skip this last part of the underground section of the tour and return to the aboveground world.

Back up at surface level, visitors are a stone’s throw away from where the imperial palace and Casimir Castle once stood. A metal structure built on top of the reconstructed palace ruins gives onlookers a sense of how big it was.

Tours span about an hour and a half. Participants are transported to a time when lakes and castles replaced buses and cigarette butts, and it’s unlikely they’ll ever see contemporary Kaiserslautern the same way again.

The Count Palatine Hall, which was built in the 1930s from stones of the former Casimir Castle, is the first stop on a tour organized by the city of Kaiserslautern that also allows participants to visit subterranean tunnels. (Phillip Walter Wellman/Stars and Stripes)

Address: Tours begin at Fruchthallstrasse 14 in downtown Kaiserslautern, Germany.

Hours: Public tours in English are held on irregular Saturdays, usually at least once a month, and begin at 11:15 a.m. Upcoming tour dates can be found at tinyurl.com/5ac66735. Private tours can be organized at various times.

Cost: Adult tickets for the public group tour cost $5; children’s tickets are $4. Private groups of up to 25 people cost $75.

Information: Participants must pre-register for the public tour by calling +49 631 365 4019 or emailing touristinformation@kaiserslautern.de.