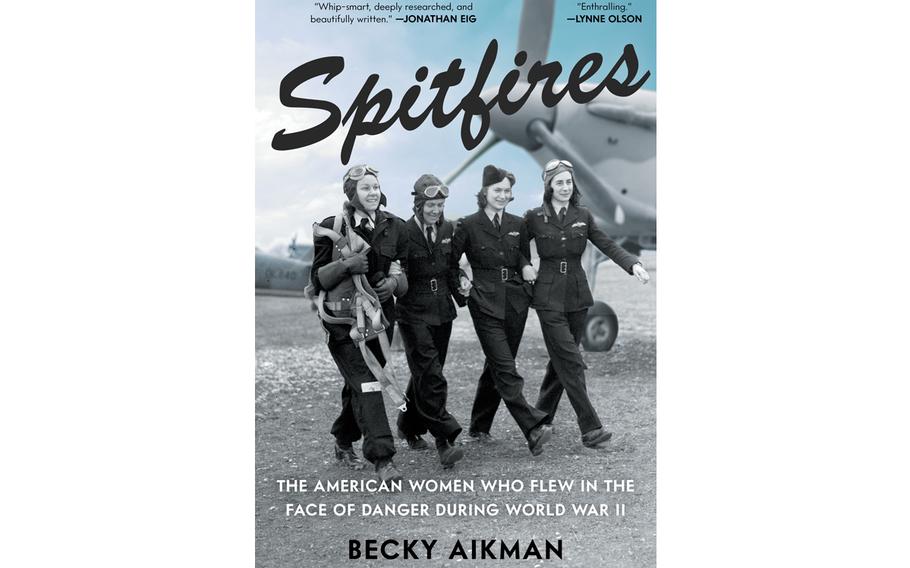

In her new book, “Spitfires: The American Women Who Flew in the Face of Danger During World War II,” journalist and author Becky Aikman tells the story of the “Atta-Girls,” a collection of American women who, after being rejected by the U.S. military because of their gender, crossed the Atlantic to aid British forces by ferrying fighter planes, bombers and other aircraft to the male pilots in front-line squadrons. (Bloomsbury)

The surge of discussion about women in the military makes the publication of “Spitfires: The American Women Who Flew in the Face of Danger During World War II” all the more timely. This lively and entertaining book by journalist and author Becky Aikman tells the story of the “Atta-Girls,” a collection of American women who, after being rejected by the U.S. military because of their gender, crossed the Atlantic to aid British forces by ferrying fighter planes, bombers and other aircraft to the male pilots in front-line squadrons.

Those fearlessly determined female pilots were the professional forebears of the women who would slowly break down barriers in the U.S. military in the decades that followed. (Half a century would pass before the first woman piloted a fighter plane in combat, and it wasn’t until 2015 that, under President Barack Obama, all combat roles were opened to women.)

And what forebears they were.

We’re introduced to a gutsy pilot who, not to be outdone by the hotshot fighter pilot boys, steered her plane at 300 mph beneath Britain’s Severn Railway Bridge, threading between support pillars with just a 70-foot gap between the water and the bottom of the bridge. There’s the “Chicago Foghorn,” who got her nickname because of her “high-decibel profanity,” and an irresistibly charming and gorgeous New Orleanian who asked if she could “borrow” her fiancé’s car, then skipped town and sold the vehicle to pay for her trip to take the flight test required to qualify for wartime duty.

“It goes without saying,” Aikman writes, “that the marriage was off.”

The 25 female pilots who made the cut for wartime duty were assembled by a larger-than-life figure, Jackie Cochran, who had made a fortune as the founder of a cosmetics company and became the world’s most celebrated female aviator after the death of Amelia Earhart. Amid rumbling that the United States would soon enter World War II, the well-connected Cochran lobbied President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, first lady Eleanor Roosevelt and the chief of the Army Air Corps to let American women, including daring stunt pilots she had recruited, serve in a flying force.

“The United States military, in all its wisdom, refused to accept women pilots, no matter how courageous and skilled,” Aikman writes.

Undeterred, Cochran pivoted in 1941 to the British, who were getting battered by the Nazis and were more than happy to bring the American women into their ragtag Air Transport Auxiliary, an outfit nicknamed Anything to Anywhere, but also Always Terrified Airwomen and the catchier Atta-Girls. (The Atta-Girls should not be confused with another group of courageous American pilots known as WASPs, an acronym for Women Airforce Service Pilots, who ferried planes and conducted test flights in the U.S. — dangerous work that cost some their lives.)

The Atta-Girls came from all sorts of backgrounds. Dorothy Furey, the New Orleanian car thief, escaped poverty and the “Gothic dysfunction” of her childhood to become the first American woman cleared to fly in World War II. Virginia Farr came from such heights of the American social ladder that there was an article about her teaching at a flight school before the war headlined: “Blue Book Miss Up in the Air, Would Teach Girls to Fly.” “Fresh from the perfumed atmosphere of a girls’ finishing school,” it read, “she invaded the pronouncedly masculine surroundings of grease and wrenches.”

Some were relatively inexperienced, others were pros. One of the first women to travel to Britain for duty, Helen Richey, had once served as Earhart’s co-pilot and had set speed and endurance records.

Regardless of their backgrounds or experience levels, their service during the war allowed for reinvention. Furey cast herself as a member of the upper class, while her wealthy colleague Farr gave off a humbler, workaday vibe.

The Atta-Girls were fearless, not just because they flew through dangerous weather in a country regularly under attack but also because they were, quite literally, learning on the fly. One of the Atta-Girls, Aikman writes, flew 18 new types of aircraft in a single month, including torpedo planes, air-sea rescue amphibians, and fighters such as the Typhoon and the Corsair, used by American Marines. All in all, they flew as many as 147 different models, mastering the intricacies of planes rolling off assembly lines that experienced male pilots had never touched.

But it is the Spitfire, which gives the book its title — and is a handy description of these groundbreaking pilots — that stirs the imagination.

“Its graceful, tapered form complemented a woman’s physique,” Aikman writes. “The Spitfire still ranks among the sleek, modern achievements of British design, like the Aston Martin sports car or the miniskirt.”

In popular culture, the plane took on the connotation of a “feisty female,” Aikman writes. Its name derives from a term of affection for the daughter of the man who ran the parent company of the firm that built it.

The nimble, single-seater Spitfire with its slim, backswept wings held a special place in the hearts of the British, who credited it with saving the country in the Battle of Britain. But that connection was especially intimate in the hearts of women pilots, Aikman writes.

“The Spit fulfilled the ultimate sense of command that drew them to flying in the first place,” Aikman writes, “that feeling of freedom — freedom from gravity, freedom from the limitations of slower, bulkier planes, freedom from the mundanity of life on the ground. For most every pilot, the Spitfire felt like her plane. It felt like her.”

Far from shying away from the action, these pilots chafed when they couldn’t get closer to it, zooming through the skies straight from the factories where the planes were built through territory imperiled by the Nazis’ lethal Luftwaffe.

When an airfield where they were based was attacked from the air by Nazis, an Atta-Girl enthused: “Great excitement.”

Their service would be marked by high-flying triumphs, yet they also lived through the heartbreak and tragedy that war brings to all, and some would be scarred by it forever.

The Atta-Girls flew hard — some crashed but insisted on returning to the cockpit. But, oh wow, do they sound like a fun bunch. If you had to be stuck in a war zone, you’d want to be with Furey and the rest of them.

“They kept multiple lovers on the line,” Aikman writes. “Sometimes they spent a crazy night or two with somebody new before both took off again, possibly to die. They conducted themselves privately the way they flew their Spitfires, with a bracing sensation of velocity and control.”

Years after the war, Furey would recall that she “drank buckets of champagne there and danced every night. … Because you never knew if you were coming back.”

All the stories of the Atta-Girls’ romances and partying enliven “Spitfires” and add to its enjoyability. But the book could have cut back just a smidgen on the abundant tales about these pilots’ lives. We get it. They were wild.

By the time the Air Transport Auxiliary was disbanded in 1945, 1,246 pilots and flight engineers had flown for the outfit, including 168 women — not just from the U.S. but also from other countries. When they were given a splashy send-off, Lord Beaverbrook, who had been instrumental in the group’s founding when he was minister of aircraft production, thanked the men who’d been involved but failed to mention the women, Aikman writes.

“The era when women pilots would fall out of mind,” Aikman writes, “had already begun.”

When they returned home, some of the Atta-Girls discovered that their flying prowess was less than appreciated in a field dominated by men. But they hadn’t gone to a war zone to prove a political point.

They just wanted to fly — and to win a war.