Dean Koontz, 77, author of more than 110 books, at his art-filled home in Irvine, Calif. (Philip Cheung/For The Washington Post)

IRVINE, Calif. — Few American writers sell as many books, live better or worry more than Dean Koontz.

"There are days that you think, 'I can't do this anymore,'" says Koontz, 77, author of more than 110 books that have sold over 500 million copies in 38 languages. "Of all the writers I've ever known, I have more self-doubt. I'm eaten by it all the time."

Fears? He has a few.

Koontz writes terrifying stories of murder and mayhem, yet is incapable of watching a gory movie. He hasn't flown for 50 years after a flight he was on encountered serious turbulence and a nun on board proclaimed, "We're all going to die." He's not big on boats, either, after an anniversary cruise coincided with a hurricane. Mostly, Koontz stays put in Orange County. Easier, safer.

He installed a towering fence, which partially obstructs the view, to protect his golden retriever Elsa from rattlesnakes. His 12,000-square-foot art-filled manse features the latest innovations to guard against wildfires. Still, every night Koontz places a freshly printed copy of whatever manuscript he's working on in the fridge — just in case of a conflagration.

So, write what you know.

Koontz is billed as the "international bestselling master of suspense," though he eschews labels and writes in multiple genres — supernatural, science fiction, young adult, manga, dog. Frequently, his books fuse several and are dusted with humor.

"You can't tie him down," his friend and fellow bestselling author Jonathan Kellerman says. "He just works all the time. He has a lot of anxiety but manages to channel it into fiction."

Ten hours a day, six days a week — more nearing the end of each book, "when momentum carries me like a leaf on a flood." He revises constantly, an average of 20 times before he proceeds to the next page.

"When the writing is working, nothing stops me," he says. He worked 36 hours straight — twice — creating "Watchers," one of his most beloved books, first published in 1987. Due to stress and his former regimen of 13 Diet Cokes a day while writing, he developed a bleeding ulcer a decade ago and almost died. Koontz prohibits distractions. He doesn't read emails — his assistant or his wife, Gerda, print them out — and won't open a browser, even to check facts or the news.

“I don’t know who I’d be if I wasn’t writing,” Dean Koontz says. (Philip Cheung/For The Washington Post)

"I never go online. Never. I don't trust myself," he says. "I know I'm a potential obsessive, and I don't want to waste time." Head down, nose to keyboard.

Koontz is warm, genial and prone to astonishing candor. Over lunch and a $135 bottle of his favorite Caymus Cabernet, he weeps several times recalling his harsh childhood in rural Pennsylvania, with a father of such spectacular cruelty that he sounds hatched from a Koontz novel, and recounts how Gerda, his high school sweetheart and wife of 56 years, saved him.

In the early days of their marriage, Koontz taught high school and worked in an anti-poverty program. He loved the students but was far from happy with the administrators. He sold a few science fiction short stories and novels published in paperback. Being a novelist was the long-held dream. Though he was raised in a house without books, writing became a refuge from the age of 8, when he would create stories and sell them to relatives for a nickel. Gerda made him a deal: write for five years and I'll support you. She told him, "If you can't make it in five years, you never will make it." He did, beating her deadline.

Koontz belongs to a small anomalous group of wildly popular, prolific authors who also regularly garner positive reviews. (Stephen King is another.) His books tend to include propulsive plots, often everyday heroes, true love and happy endings, though his childhood promised nothing of the sort.

"Dean believes — and I think this is reflected in his work —that good will prevail, and that kindness is a virtue worthy of celebration, even when circumstances seem dire," says Jessica Tribble Wells, executive editor of Amazon Publishing. (Amazon founder Jeff Bezos owns The Washington Post.)

He dwells in that rarefied air of King, John Grisham and James Patterson, publishing blockbusters with legions of fans who inhale everything they write. Though he rarely travels, Koontz conducts virtual events, writes a monthly newsletter and responds often to ardent readers.

"All his characters are on an adventure. They want a normal life but get pulled into these situations. I believe Dean lives his books," says Kathie Salembier, 72, a retired bookkeeper in Fair Haven, Mich., who has mailed fan letters to only three luminaries: Elvis, Eminem and Koontz. The novelist responded three times. "My prized possessions," Salembier says.

When Koontz decided to change publishers in 2019, he received eight offers, all but one guaranteeing mid-seven-figure advances for each book. Many houses submitted marketing plans of one to three pages, he says, but Amazon Publishing's "must have been some 40 pages."

"What Dean wants is as many readers as possible," says Richard Pine, Koontz's co-agent along with Kimberly Witherspoon. "One of the things that got me reading his books is that he's such a better writer than he sort of needed to be." Koontz is withering about past editors who didn't believe in his promise.

Koontz writes two books each year. "The House at the End of the World" was released in January; "After Death" will arrive in July. "At my age, it's kind of astonishing," he says. Koontz doesn't do outlines. He feels they're constraining. He starts with characters, a premise, perhaps a scene or two. "Life Expectancy," one of his favorites, opens with a deranged, chain-smoking, aerialist-abhorring menacing clown named Beezo in a 1970s maternity waiting room.

"I give the characters free will," he says. "The novel becomes organic and unpredictable and much more interesting to me."

When Koontz first discovered John D. MacDonald, who remains among his favorite authors, he devoured 34 books in 30 days. Koontz doesn't dwell on his ability to conjure up fresh stories.

"I'm always afraid that if I think about it too much, it will all stop," he says. Tribble Wells writes, in an email: "Dean is a rarity among writers: I've never known him to have writer's block."

Also, Koontz says, "I don't know who I'd be if I wasn't writing." It's the road map. He craves structure.

He and Gerda, who have no children, live in a gob-smacking home graced with a vast collection of art deco painting and furniture, Chinese art (mostly from the Han, Sung and Tang dynasties), Japanese sculptures and screens from the Meiji period, and 10 canvases by contemporary painter Kenton Nelson, his style reminiscent of Works Progress Administration (WPA) social realism. This house is a serious downsize from their previous 29,000-square-foot estate in Newport Beach, Calif., which took 10 years and three different architects to construct. He refers to the environment the couple has created as "Koontzland."

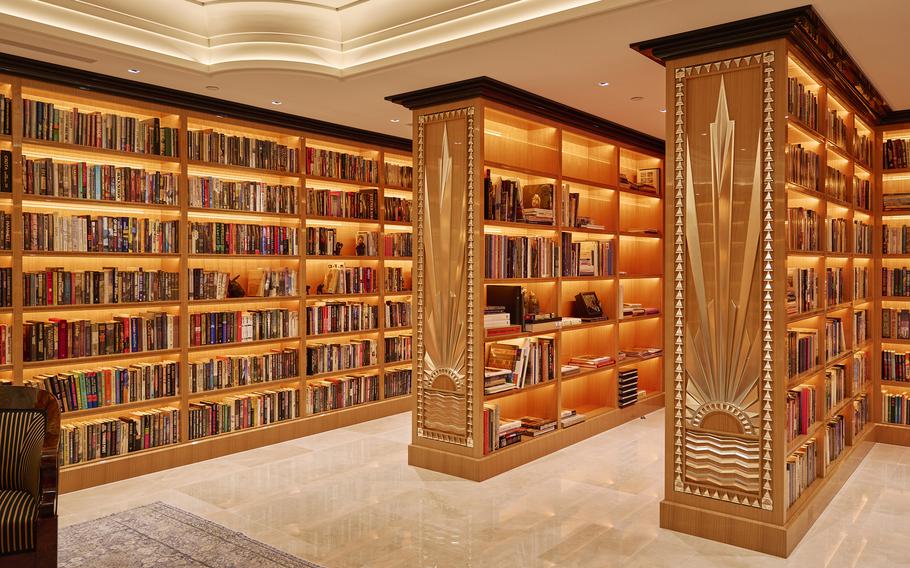

The Irvine house is maintained by a staff of five: three housekeepers, a house manager and an assistant house manager. The garage, like everything else, is immaculate, regularly painted to remove all nicks and smudges. There's a spa, sauna and steam shower that he never uses "but it relaxes me to look at it." Koontz had the indoor pool (there's an outdoor one as well) removed to create a custom wood-paneled, exquisitely lit, Architectural Digest-worthy athenaeum for his collection of 20,000 books by other authors, mostly first editions. It was renovated in seven months during the pandemic, at substantial cost, with the exquisite custom cabinetry found throughout the home. He removed the gym to house a second library with nearly 9,000 unique editions of his own novels.

Dean Koontz at his temporary 12,000-square-foot home in Irvine, which he had renovated in seven months during the pandemic. He owns another house, which is undergoing a major renovation, in the same development. (Philip Cheung/For The Washington Post )

This is Koontz's temporary home.

We take a brief drive in his Lincoln up the road in the same gated compound to visit the other house, where a fleet of tradespeople are working. The interior and exterior have been stripped to the studs. What is wrong with his current home? "Flow." Also, not enough yard for Elsa. They hope to have the renovation completed in two years, perhaps sooner.

Dean Koontz had the indoor pool of his Irvine house removed and installed a custom library of 20,000 books by other authors, many of them first editions. (Philip Cheung/For The Washington Post)

"His other art, along with writing, is crafting these structures like stories. It's a very similar impulse," Pine says. "The world of writing, and of design, along with Gerda and the dogs, are what really give him joy and focus him. For someone who doesn't want to leave, you might as well build a place that you don't want to leave."

It is an understatement to call Koontz and Gerda dog owners. His dust-jacket photos invariably include a photo of his dog. His books feature them. His author bio notes that he lives with Elsa and "the enduring spirits of their goldens Trixie and Anna."

Commemorative plaques for both golden retrievers are featured in a backyard meditation area, not unlike Graceland’s. The urns containing their cremains reside on a fireplace mantle in the couple’s bedroom. Koontz and Gerda hope that, when their time comes, their ashes will be buried with them. The couple eats out regularly, patronizing only restaurants that allow dogs, and where Elsa is greeted like a rock star.

Commemorative plaques of Dean Koontz’s beloved deceased golden retrievers in the backyard. Their ashes reside in urns in the couple’s bedroom. Koontz and his wife Gerda hope that, when their time comes, their ashes will be buried with them. (Philip Cheung/For The Washington Post)

In 2009, Koontz published "A Big Little Life," about Trixie. Like many dog memoirs, it is also a memoir of its author, a vessel for his life story.

Koontz shares plenty in that book. That he irons his underwear. That he isn't particularly fond of most other writers: "I found this community as a whole to be solipsistic and narcissistic and irrational." That the experiences of getting his books adapted to the screen have been mostly unrewarding, "because they're all blithering idiots in Hollywood." That editors doubted his ability to be a bestselling author. That he repeatedly proved them wrong. That he lived in a house without an indoor bathroom until age 11. That his father was a difficult, violent, womanizing alcoholic, holding 34 jobs in 44 years. That life, despite his desire to search for goodness, can be punishing and unfair given that his mother, "a wonderful person," died at age 53 while his father, "who never met a vice he didn't like," lived three decades longer.

Over a languorous lunch, Koontz shares more, including the time that his father pulled a knife on him when the writer was in his 40s.

"A mess of a person," Koontz says, "I took care of him financially but wouldn't let him live with us" for the final 14 years of his life.

Koontz remains amazed that his life turned out as well as it did. "I was the son of the town drunk. Where did the storytelling come from?" A gift.

He remains an optimist. In his books, good invariably triumphs. He says, "It's been my life experience, and it's the way I want life to be."

Koontz designed a better, bigger life than his childhood suggested. He wrote himself a better story. More than 110 of them.