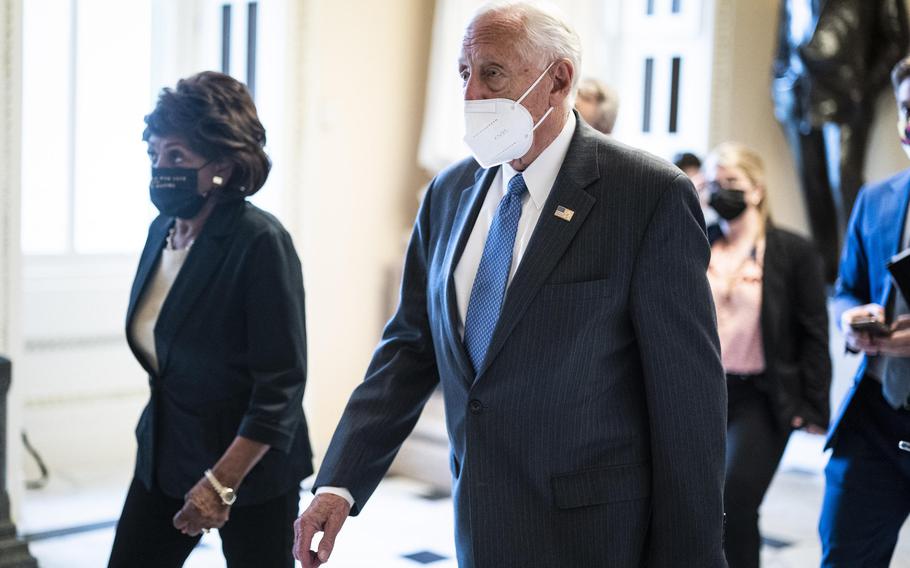

House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer of Maryland and other Democratic leaders are expected to ask members to spend more time in Washington to get the Biden agenda passed. (Jabin Botsford/Washington Post)

WASHINGTON - One of the toughest jobs on Capitol Hill has always been the scheduler: that aide who helps lawmakers juggle their committee meetings and votes, their constituent work back home and their political fundraising, all while carving out some time for their family.

That job is about to get a lot more difficult in the months ahead.

Democratic leaders are reluctant to say it out loud, but circumstances are about to dictate that they blow up the legislative calendar to build more time in Washington if they want to approve President Biden's ambitious agenda.

When the Senate finishes up Thursday, the chamber will shut down until July 12 for an unusually long Independence Day recess. After returning for four weeks, the Senate is supposed to break by Aug. 6 for more than four weeks of the beloved August recess. That's a nearly 75-day run from late June through Labor Day in which current planning would have senators here voting about 16 days.

The original House schedule is even more impractical. When members of the House leave town July 1, they are slated to be in session just two of the next 11 weeks.

Yes, you read that right. From July 2 through Sept. 19, the House is only in session for nine days.

All as the legislative agenda includes expectations of approving a $4 trillion compilation of infrastructure and social welfare programs, possibly broken into a complicated two-track system; funding federal agencies before a Sept. 30 deadline to avoid a government shutdown; extending the Treasury's borrowing authority by late summer or early fall to avert a default on the federal debt; and potentially other major actions such as a Supreme Court vacancy if one of the justices announces a retirement when their term ends later this month.

Democratic leaders are getting ready to gently break the news to their rank-and-file members, who often take the contradictory positions of complaining to their leaders about not getting enough legislation approved and demanding to spend more time at home with their constituents.

"House Democrats are committed to advancing President Biden's ambitious agenda to build back better. The House schedule will ensure time for the committee process and floor consideration of legislation as we get our work done for the American people," Katie Grant Drew, a top Hoyer adviser, said in a statement to The Washington Post.

The House and Senate calendars got drawn up long before the respective leaders could predict the summer logjam ahead.

The House calendar, overseen by Hoyer, was released Dec. 2, a dark time when America entered the peak of the pandemic and no vaccines were in use yet. Social distancing still mandated less travel back and forth to Washington than a normal year. Hoyer formalized the practice of "committee workweeks" in which lawmakers were home and would hold hearings remotely.

In addition, as House leaders prepared that initial schedule, Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., was still Senate majority leader and Republicans were favored to win two runoff races in Georgia on Jan. 5 to retain the Senate majority into this year.

Most Democrats liked the concept of spending so much of summer away from what they believed would be a gridlocked Capitol.

Senate leaders released their calendar just before Christmas with the fate of Georgia's elections increasingly unclear and no sense that much of late January and February would be consumed by an impeachment trial after Donald Trump's supporters stormed the Capitol Jan. 6 trying to block certification of Biden's win.

Those Democratic wins in Georgia gave Democrats the Senate and launched a series of bold initiatives. Hoyer has already juggled the schedule once, in late January, to allow more time in the Capitol for the swift approval of the $1.9 trillion coronavirus rescue plan by early March.

After that, Biden entered negotiations with Republicans to determine if there was bipartisan support for his agenda, slowing the pace of Congressional action from the usual breakneck pace under a new administration.

Through Thursday, the House had held 172 roll call votes, according to congressional records. At the same point in 2017 and 2009, the House had already held more than 300 votes each in the first five months of Trump and Obama administrations.

Changes to Senate rules make vote comparisons pointless, but this year's Senate is off to a slower start in one key data point.

By mid-June of 2009, the Senate had already been in session 91 days. So far this year the Senate has been in session 86 days, and at least seven of those were for the impeachment trial in which no legislative business was allowed to be considered.

The good news, for Biden, is that bipartisan talks among more than 20 senators produced a potential breakthrough on a more than $1 trillion package of mostly traditional infrastructure projects that, if the deal can be finalized, would move separate from the remaining $3 trillion in other Biden agenda items.

The bad news is - especially for those schedulers whose bosses want to travel on delegations abroad or spend time with family in August - these bipartisan talks are likely to go on for a while and set up a time crunch that will finally force Hoyer's hand to claw back that time away from the Capitol.

"We don't want to rush it and get it wrong. We want to take the time and do it right," Sen. Rob Portman, R-Ohio, said Thursday.

Portman, the lead GOP negotiator in the infrastructure talks, voiced some optimism that this entire package could come together by the end of July because a majority of the group's proposals are pulled from existing legislation in the Senate.

"It's possible, it's possible," he said, before dismissing the sentiment from senior White House aides who told House Democrats on Tuesday that they needed a decision within seven to 10 days. "No we don't. We're not going to and we shouldn't, that would be bad. We're going to do it right."

These protracted negotiations set off panic among some liberals, such as Sen. Ed Markey, D-Mass., who was in the House in 2009 and worked on climate legislation and the committee work that became the Affordable Care Act.

Markey said that he has been reminding Democrats that delays in those talks 12 years ago eventually ended with climate bill stalled and an imperfect version of the health law that didn't pass until the spring of 2010.

And he's concerned that going with the bipartisan package, rather than a single Democrats-only bill, would undercut the most liberal agenda items and endanger their passage later in the year.

Which only leaves one possible route to moving the agenda, tossing aside a lot of that time out of Washington and instead creating a new, more realistic schedule.