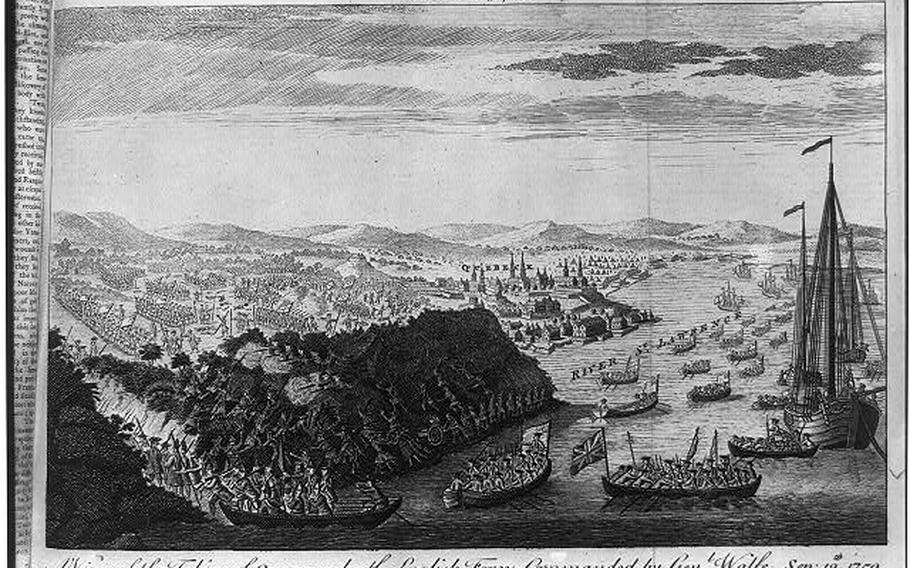

An engraving of the Siege of Quebec on September 13, 1759. The HMS Hind, which participated in the battle, was found and identified off the coast of the Scottish island Sanday. (The Library of Congress)

LONDON — Ferocious winter storms are not unusual on the remote island of Sanday, jutting off Scotland’s northern coast. But when a storm buffeted a beach there last year, a long-buried surprise was revealed beneath the sand: A 30-foot-long wooden shipwreck.

The mystery of the oak hull’s provenance was revealed Wednesday by a team of archaeologists and historians: The wreck was probably HMS Hind, a British frigate that once fought in the American Revolutionary War and sank off the island over 230 years ago.

The 18th-century Royal Navy vessel, which also participated in the 1759 Siege of Quebec and was later repurposed into a private whaling ship, was on its way to the Arctic in March 1788 when it likely struck a reef, experts say.

“The records suggest a storm pushed it onto the rocks,” said Ben Saunders, a marine archaeologist at Wessex Archaeology, a research firm commissioned by Scottish authorities to help identify the shipwreck, in a phone interview Wednesday. “It probably struck that reef and came to pieces.”

Researchers were able to identify the mystery vessel, which appeared in February 2024, using dendrochronology - a wood-dating technique that uses timber rings to identify the year they grew within a tree. The results suggested that the ship was made of timber felled in southern and southwest England during the mid-18th century.

By cross-referencing the time and location with an existing list of known shipwrecks on the island chronicled from local archives and reports, researchers were able to rule out foreign ships and those that didn’t match the dates.

The process of elimination revealed one ship: the Hind.

At the time of the wreck, the ship had been sold by the British navy to a London merchant, who christened it the Earl of Chatham and repurposed it as a whaler. It was on its way to its fifth whaling expedition to the Arctic, most likely in the Greenland Sea, the team found. During the late 18th century, demand for whale oil - which was used for lamp oil, machinery lubricant, and more - was booming.

Before its career as a whaler, according to maritime archives, the ship had a storied career as a Royal Naval fighting vessel, traveling as far south as the Caribbean and seeing action in at least two wars.

After its construction, in the southern English city of Chichester in 1749, records show the Hind stationed in Jamaica - then a British colony where enslaved people from Africa were brutally exploited and forced to work on sugar plantations.

According to Saunders, the vessel was then deployed to North America, where it fought against France in the sieges of Louisbourg and Quebec in the French and Indian War. During this conflict, Britain fought to dislodge France from its colonial foothold in Canada, capturing Louisbourg in 1758 and Quebec the following year. The war ended with British control over France’s Canadian territories.

During the Revolutionary War, the Hind played a crucial role in protecting British cargo. It did “convoy duty across the North Atlantic between Britain and the North American colonies during the American Revolutionary War, protecting merchant vessels from American and French raiding ships,” Saunders said.

When the war began, the British navy far outnumbered its nascent American counterpart. But American revolutionaries came up with ways to threaten the British fleet. By converting merchant vessels into armed ships - privateers - the Americans were able to launch successful raids on vulnerable British shipping convoys.

“The American Revolutionary War was a complex time for the Royal Navy. They suffered the first losses of vessels to the American Navy, which caused huge consternation in Britain. ‘How can we possibly have lost vessels to this upstart group of colonies?’” Saunders said, referring to Britain’s sense of bravado at the time.

The Hind’s crew proved relatively adept at its task, intercepting at least four American privateers between 1780 and 1781, maritime records show.

At the height of its naval prowess, Saunders said, the triple-masted vessel would have been armed with 24 guns, crewed by around 200 men, and measured around 100 feet in length: “It was a sizable, fighting vessel.”

Records suggest that its crew of 56 sailors aboard what was then the Earl of Chatham survived the 1788 shipwreck, the team said. Islanders likely pulled the wreck to the beach’s high-water mark, giving them scavenging rights over its timber and any treasures - and afterward, it was entombed in sand.

According to a Wednesday statement from Wessex Archaeology and Historic Environment Scotland, which funded the research, climate change — which, the statement said, made increased storminess and unusual wind patterns more likely — revealed the wreck, in 2024.

“Changes to coastlines, which are predicted to accelerate in coming decades, could make similar finds more common,” it said.