Contemporary health providers stand-in as Civil War surgeons during a re-enactment at the Spangler Barn in Gettysburg, Pa., June 7, 2025. From left, Drs. Jon Willen, William Campbell and Don Levick and Mark Quattrock, director of the Blue & Gray Hospital Association. (Joseph Ditzler/Stars and Stripes)

Most Civil War histories evoke the bravura of 19th century military skill, of masses of men moving across open fields to face other orderly masses of men and commence killing each other.

Few books focus solely on the gruesome aftermath of Civil War combat, beyond the unburied dead that carpeted the battlefields and the shrieks and moans of the wounded. Though the nation this year marked the battle’s 162nd anniversary, it paid scant attention to the plight of tens of thousands of men left broken on its fields.

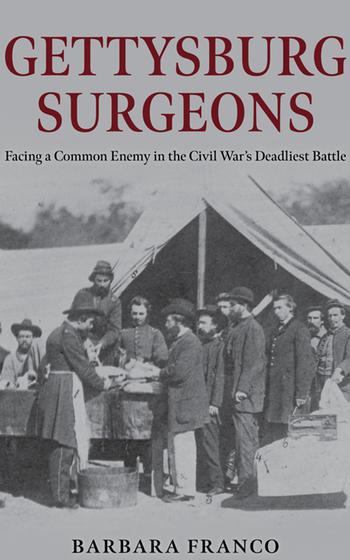

“Gettysburg Surgeons: Facing a Common Enemy in the Civil War’s Deadliest Battle,” explores the experience of army surgeons, Union and Confederate, in a complicated, textured new telling of the three-day fight in south central Pennsylvania.

Its author, Barbara Franco, is a former executive director of the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission and the Gettysburg Seminary Ridge Museum, a landmark of the first day’s fighting at Gettysburg and one of its largest field hospitals. Scores of buildings — colleges, schools, churches, barns, farmhouses — were pressed into service as places to gather and treat the 20,000 wounded during and after the battle.

“Gettysburg Surgeons: Facing a Common Enemy in the Civil War’s Deadliest Battle,” explores the experience of army surgeons, Union and Confederate, in a complicated, textured new telling of the three-day fight in south central Pennsylvania. (Barbara Franco)

Eventually, one organized hospital, Camp Letterman, replaced the haphazard field hospitals to care for the remaining, worst cases of battle casualties. The tent city lasted into early November; some of its staff lingered on to hear President Abraham Lincoln’s address at the battlefield cemetery’s dedication that month.

Franco’s 340-page volume, recently available from Stackpole Books, deserves a spot on any shelf dedicated to America’s most dissected war. Franco does more than raise up the narrative of the beleaguered surgeons and assistant surgeons who probed and sawed their way through the conflict, she opens a perspective rarely seen in histories of the period.

Take for example her description of the fields north of Gettysburg following the battle’s first day on July 1, 1863. A local woman, Harriet Bayley, ventured out into territory now under Confederate control, carrying a “market basket full of bread and butter and wine, old linen and bandages and pins.”

She found suffering Union soldiers still lying in the open, under a summer sun, where they’d spent the past 24 hours without food or water, much less medical care.

More than 1,600 wounded soldiers were treated inside Spangler Barn, recently restored by the Gettysburg Foundation. It served as the hospital for the Union Army’s 11th Corps during the 1863 Battle of Gettysburg. (Joseph Ditzler/Stars and Stripes)

In another episode, surgeon Francis Huebschmann of the 26th Wisconsin infantry — caught in the town as it was overrun by Confederates but still tending to casualties — walked into the open fields nearby and “implored in a booming voice to the troops to stop firing at the wounded.”

“Gettysburg Surgeons” also plumbs an overlooked aspect of the fight, that Union and Confederate surgeons commingled in the borough after Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia drove the Union soldiers out of town and onto Cemetery Ridge, and after Lee’s retreat July 4.

Surgeons, as the army physicians were called, of both sides cooperated to a degree, tending to the wounded of both sides and remaining with their patients even as their positions were overrun or their armies retreated.

After the war, these military medical professionals changed the course of medicine, from private practice to public health.

“They endorsed medical care based on science, clinical observations, and results, rather than unsubstantiated medical theories,” Franco writes.