An F-15C Eagle from the 48th Expeditionary Operations Group prepares to leave Cervia Air Base, Italy, March 27, 1999, for combat above Yugoslavia. NATO ramped up its air campaign at the end of the month. (Ward Sanderson/Stars and Stripes)

This article first appeared in the Stars and Stripes Europe edition’s Sunday Magazine, May 9, 1999. It is republished unedited in its original form.

EDITOR’S NOTE: There are stories, and then there are stories. Stars and Stripes reporters and photographers have been filing news stories from Albania and Macedonia over the last six weeks as the NATO air campaign intensified and floods of refugees flowed out of Kosovo. We’ve given readers a glimpse into the lives of refugees and airmen, sailors and soldiers alike.

The guided missile destroyer Gonzalez in the Adriatic Sea fires Tomahawks at Serbian targets in Yugoslavia, March 25, 1999. Each missile carried a 1,000 pound warhead. (Ward Sanderson/Stars and Stripes)

War’s beginning

By Ward Sanderson

Modern warfare is only a video game until one of the blips heads straight for you.

The war with Serbia began March 24 and it did so from the sea. The guided missile cruiser Philippine Sea lunched Tomahawk missiles about 6:45 p.m. and watched from the deck of a second ship, Gonzalez, somewhere in the Adriatic.

Reporters brought to the guided missile destroyer Gonzalez for the show bantered about the other wars they had seen, how many pounds of warheads rattle teeth and glass for just how far. Sailors onboard took pictures and rolled video cameras. It was like a class reunion.

Then Phil Sea fired and the war, for us, was only far-off silver flashes. Some sailors were disappointed by the show.

Around midnight, we fired. That show didn’t disappoint. A concussion rang the deck like a tuning fork. Fire burned away the oily cloud of the Adriatic evening, and for a few seconds it was noon. Sailors whooped.

The next night, Gonzalez launched about 18 missiles. Maybe a dozen reporters or photographers plus a few sailors watched from deck.

The first Tomahawks threw down a chunk of its hull; it smacked the deck and clattered, smoking, at our feet. On about the seventh launch, one missile went up, up, then its booster rocket ran low on fuel. Instead of switching to cruise phase, which would fly to its mark in Yugoslavia, it stumbled in the air like a drunk.

The missile that “risks no U.S. casualties” decided it wanted to return to the nest. The comet grew; bigger, bigger, brighter. I’m thinking, “It’s supposed to do that, yeah?”

You want to run, but where would you go? And how stupid would you look? So we flinched and stared, deer-in-headlights, for God to make up His mind.

He did, about 150 yards from the deck. No explosion, just a touchdown splash.

Someone called “O-My-Goodness” over the radio. The bridge was abuzz.

The reporters, notebooks in hand, marched single-file toward the interior of the ship. They had a scoop. But nobody whooped.

Illuminated with the same type of night vision goggles used by U.S. forces, troops in a 1st Infantry Division humvee keep watch over the Yugoslav border region in the early morning of March 30, 1999, as NATO bombers could be heard overhead beginning their strikes into Kosovo. (Jon R. Anderson/Stars and Stripes)

On the border

By Jon Anderson

It was Day 2 of the air war against Yugoslavia and, truth be told, I had no idea where I was.

I knew I was somewhere in northern Macedonia — very close to the ill-defined Yugoslav border. But exactly where and in what direction I was heading was the part I was having trouble with.

I had spent the night on Macedonia’s northern frontier hunkered down with a cavalry troop of 1st Infantry Division soldiers who had been quietly ordered up to the border the day before as the bombing campaign kicked off. As we all shivered through the night, flashers could be seen over the distant mountains, while the NATO air armada pressed the attack.

These soldiers were here because NATO leaders worried that Yugoslav president Slobodan Milosevic might try to retaliate against the attack with a ground counteroffensive against Macedonia.

These troops, until recently, had been wearing blue berets as part of the U.N. peacekeeping mission on this order. But things were decidedly more tactical now as troops manned loaded heavy machine guns atop armored Humvees and personnel carriers.

Capt. Keith Igyato, commander of B Troop, Task Force Saber in Macedonia, confers over a map with two British electronic warfare specialists, March 29, 1999, near the Yugoslav border. Soldiers from the 1st Infantry Division were patrolling along the troubled Yugoslav border to help make sure Slobodan Milosevic’s forces didn’t try to make an end run into neighboring Macedonia while NATO warplanes pressed their attack. (Jon R. Anderson/Stars and Stripes)

As a former grunt who had served a stint with the infantry, I knew the almost palatable sense of purpose — and cool excitement — that could be felt rippling among troops who had been chosen to go out on this mission.

As a journalist, I was one of the few correspondents who was any where near the combat zone with American soldiers.

It was, as journalists like to say “a good story.” But my reporting wasn’t going to do any good if I couldn’t get the story to my editors.

A sympathetic Staff Sgt. Agard Lindsay had watched my frustrated attempts to get my dispatch out over my cell phone. The rugged hills weren’t steep enough to prevent me from getting through, but we were remote enough that the connection broke off almost immediately.

A supply run would be going out later in the afternoon, but chances were slim I would make it back to the Macedonian capital of Skopje to beat my deadline.

Breaking out his map, Lindsay, a soft-spoken tank commander from St. Lucia, said I could probably hike south to a hard-top road where I could meet up with the driver Stripes had hired. It was no secret this was an ethnic Serb-dominated area of Macedonia, so I’d be taking my chances on local goodwill.

There were two routes I could take, Lindsay said. The first was a beeline, straight over two short, steep hills to a ridge line overlooking the road. The other was more circuitous, following a muddy goat path.

“Whatever you do, just don’t go north,” Lindsay reminded me as I shouldered my rucksack, stuffed with my flak vest, helmet, camera bag and laptop.

With as much former-grunt bravado as I could muster, I told him not to worry. Yugoslavia was the last place I wanted to go, I said as I headed down the hill, following the beeline route.

It didn’t take long to figure out that was going to be a nonstarter. I soon found myself floundering in thick brambles and prickly thorn-spiked vines. I wiped away the sweat and decided to turn around and head for Route B.

Three hours later, there I was, wondering where the hell I had ended up.

I had ignored the cardinal rule of land navigation: Carry a map and compass.

The path I set out on had, after a few miles, come to a crossroad of sorts. Picking one of the three options before me, a few miles later I found myself staring at a fork in the patch. I took the left, for no particular reason.

Soon, I found myself wandering through a small village of a few stone and wood homes with chickens scratching in the dirt yards. A woman cleaning clothing in a stream bed and a toddler sitting nearby stared as I hiked past.

Before me I could see the path wind up a hill. Maybe there I could get my bearings.

But as I continued to hike, something just didn’t feel right. Lindsay’s warning echoed in my ears.

“Okay, so is this north or what?” I asked out loud. I had no idea.

Swallowing my pride, I went back to the woman to see if I could ask directions. No joy. Not only was her English worse than my pigeon Macedonian, my futile attempts at drawing a map in the dirt appeared to be little better than chicken scratch.

A gap-toothed smile was all I got for my efforts, until a farmer chugged by on a small tractor. While his English was no better, we were able to piece together a map with rocks and twigs and scratches in the dirt. An hour later, I was on the road and soon found the promised driver and we got the story and pictures filed in a classic deadline-driven frenzy.

My only regret is that in my rush I didn’t take a picture of that crude map the farmer and I put together, especially of the arrow he drew pointing to the north to Yugoslavia — right along the path I had been walking.

Ducking for cover

By Marni McEntee

Something just wasn’t right.

I was lifting weights at the Air Force gym on Eagle Base in Bosnia when a couple of guys dropped their dumb bells and ran to the door to listen to their hand-held radios over the loud music inside.

The next thing I knew, the six or eight guys in the gym were throwing on flack vests and helmets and rushing outside. I was stunned and stood watching the men run past me, hoping for some direction.

But they were all business and almost all gone. I turned to someone I had met a few minutes earlier and said: “What do I do?”

“Get to a bunker, m’am,” he ordered. So I grabbed my daypack and sprinted out the door, still not sure what was happening. As I jumped over fallen tree branches to the nearest shelter, I could hear the air-raid siren wail. It was something I’d only heard before on the soundtracks of World War II movies.

I ran hard.

Within minutes, the base was completely quiet, except for the squawking of radios. “This is real world!” the voice said.

After the sun sank below the mountains, teams of soldiers patrolled the base switching off errant lights. Soon, all was black.

I spent the next three hours in the chill of the dark bunker — one of the few on base without electricity. I used the tiny flashlight I always carry to take some notes as I talked to the soldiers there. Since I was only wearing shorts and a T-shirt, one of the airmen gave me his battle dress uniform shirt.

I called an editor on my cell phone — getting reception by poking my head outside the bunker door. He told me there were televised reports that American jets had shot down two Yugoslavian MiG-29 jets over Bosnia.

It was the first real touch of the Yugoslav conflict we had had in Bosnia. The reporter in me was exhilarated, but I was a little scared. Was Eagle Base a target?

As we waited for the all-clear, one airman told me he had seen the two American jets pass overhead earlier and fire missiles at a target beyond the horizon. It wasn’t until that moment he realized the missiles had hit their mark.

The shootdown served to remind everyone that Bosnia was still very much in the Balkans.

The next day, I headed to the mountain village of Teocak with a gaggle of other news and broadcast reporters to view one of the downed MiGs, which was little more than a scorch mark on the grass. All that was left of the supersonic, multimillion dollar fighting machine was a tiny pile of burnt, twisted metal.

Nearby, two local men cooked a skinned lamb over a small wood fire while watching the gathered military and media types take pictures of the fallen plane.

It wasn’t much of a memorial to the Serb pilot who had the audacity to cross into Bosnia airspace. But unlike his plane the pilot got away.

Refugees — forced onto trains in Pristinia, provincial capital of Kosovo — at a border crossing in Blace, Macedonia, on April 1, 1999. The Macedonian government estimated that at least 40,000 refugees had entered the country since airstrikes began over Yugoslavia. (Jason Sandford/Stars and Stripes)

A flower of hope

By Jason Sandford

The woman from Pristina said her name meant “flower of life.”

Standing at what felt at the time like the epicenter of human misery, 27-year-old Luijeta Hamidi’s words caught me by surprise. Her black-brown eyes locked on to mine, I couldn’t ignore the tremolo in her speaking voice or the visceral emotion I saw in her quivering hands.

Blustery March was winding down and I had been writing about the squalid conditions in a refugee camp at the border crossing in Blace, Macedonia, for about a week.

Calling it a “camp” was a stretch. Macedonian authorities, totally unprepared for the human wave that crashed over their borders, kept the tens of thousands of refugees in an open field where they had landed.

There was little shelter from the piercing-cold wind and drenching rain. Sheets of plastic were being distributed and, with blankets, tied up on sticks to form lean-tos. A river running alongside the open field served as a toilet. Dead bodies of several babies, newborns to the camp of mud and filth, also were sent down the waterway.

Garbage piled up everywhere. The stench of dirty diapers, bloody bandages and campfires mixed with a sweaty smell of fear. It stuck to my clothes and haunted my sleep at night.

So signs of optimism, hope, even idealism, in the face of tragedy came as a welcome surprise. The resiliency of the human spirit never ceases to amaze.

I found it in child refugees chasing butterflies in a tent city; in a young man who promised to call me and show me his home and his city when the fighting was over; in the young woman who said she hoped that telling a reporter her story would help the world understand the suffering her people were enduring.

But when Luljeta Hamidi spelled her name for me after a short interview and told me its meaning, I simply had to stop for a moment.

Here was a woman who had fled for her life from Serbian paramilitary groups that had been systematically rounding up ethnic Albanians in her city, Kosovo’s provincial capital. She had been forced to leave with nothing but the clothes on her back and what few personal effects she could carry. Here was a woman who watched loved ones threatened and beaten. And in seeking a safe haven, she found only more torment here in this “camp” while awaiting an uncertain future.

Luljeta had been stripped of everything she held dear.

She had only her name. And she dearly held to the hope it carried.

Children nap in the afternoon sun outside their family tent at the Brazda Refugee Camp near Skopje, April 9, 1999. (Sally Roberts/Stars and Stripes)

A sense of worth

By Stefan Alford

The threshold for suffering increases when the alternative is death.

So what if you shiver on a cold, hard ground? So what if your main diet is bread and bananas? So what if you haven’t had a shower in weeks? Does it matter that your body aches and your mind is filled with worried thoughts for missing family members?

Would you rather be dead?

For hundreds of thousands of Kosovar refugees in Macedonia — from where I reported — and Albania, the answer is obvious.

And despite the best efforts of the United Nations and numerous aid organizations helping with refugee relief efforts, the camp conditions for those displaced from Kosovo are harsh.

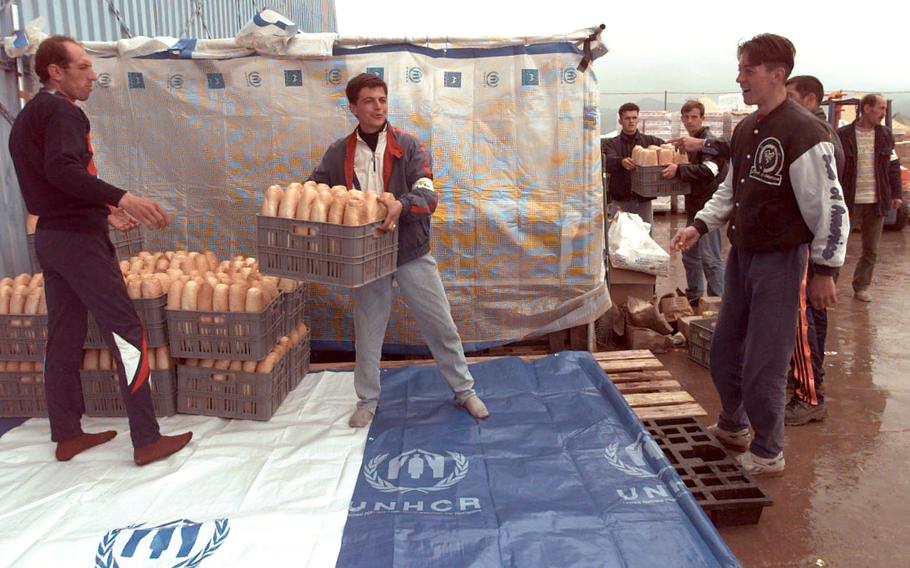

Volunteers move crates of bread to drier storage at the Brazda refugee camp in Skopje, Macedonia, April 23, 1999. The workers were Kosovo refugees volunteering their time to the Catholic Relief Service. (Ron Alvey/Stars and Stripes)

There’s a lack of sanitary facilities, they’re overcrowded, and the rain, mud and freezing nighttime temperatures make life miserable. But a life with misery is better than no life, and to survive one learns to cope.

Seeing how these people have adjusted to their situation is inspiring. Their whole world has been taken from them — everything they knew and everything they had is gone. Yet there is still optimism and hope and, perhaps most tellingly, humor.

To be able to share a smile and laughter with those in the camps makes you feel everything will eventually be all right for them. They have come through the worst with their spirits intact.

A young ethnic Albanian girl sharing a “knock-knock” joke taught to her by an aid worker or an older man laughing about how it took Serbian soldiers three attempts before they finally managed to set his car on fire underline the resolve in the face of tragedy.

A resolve not to have taken away from them that last and most important possession they carry — their sense of worth as human beings.

Mud City, Albania

By Marion Callahan

I lived miles from camps housing thousands of refugees fleeing horrors of their homeland, and I have none of their stories to tell. I lived a week in a foreign land, but I have little to share about the food, culture and nature of its people.

Beyond the towering mountains that-surrounded me and nearly 3,000 U.S. soldiers at Task Force Hawk’s base camp at the Tirana airport, much still remains a mystery.

This might be all I know of Albania.

A mud-soaked tent city lacking showers and running water seemed a harsh and bleak introduction. Sporadic gunfire at night and incessant rain showers were poignant reminders of how far from home I was.

Spc. Daryl Dusharm, Spc. Geoffrey Johnson and Jacob Ainsworth carry supplies through the mud that surrounds Task Force Hawk base camp in Tirana, Albania, April 19, 1999. (Marion Callahan/Stars and Stripes)

Yet within this armed camp, guarded by Bradley fighting vehicles and infantry soldiers toting M-16s, there was plenty to discover about the world of a soldier.

An advance crew from the 1st Battalion, 6th Infantry from Baumholder, Germany, had rolled into a wet, grassy field five weeks ago to set up an area for 24 Apache helicopters. More concerned with fortifying the perimeter than pitching tents, the men found night upon them before they had shelter. They slept huddled under ponchos shielding themselves from the wind and the rain.

After a week, hundreds more streamed into the bare-bones camp, which took a relentless beating from Mother Nature. Rain quickly turned the ground beneath our feet to muck.

A U.S. Army soldier sits atop an Avenger, Air Defense Artillery Unit, covered in the ubiquitous mud, parked at Rinas Airport, Tirana, Albania, April 27, 1999. (Mark Allen/Stars and Stripes)

No one was exempt from the “suck.”

We all trudged through the odorous quagmire, scouring for footsteps to follow. The thick, crusty coat of mud camouflaging my laptop and camera bags testify to the numerous times I fell. Soldiers were quick to point out the shallow routes, carefully warning me to stay clear of the deep boot-sucking pits.

We all faced the grueling task of taking mud-dripping boots off at night, and putting them back on in the morning.

“Embrace the suck,” was the phrase most familiar at those two low points of the day.

Throughout the week, I spoke with hundreds of soldiers and listened to their stories. One female soldier canceled her wedding plans because of the deployment. Several fathers won’t be home to see their babies born.

These are all sacrifices that come with being a soldier.

I learned a great deal about base camp life in a few short days.

I learned to savor wet wipes and scout for flattened scraps of cardboard boxes to lay beneath my cot. I learned which MREs come with jalapeno cheese and Jolly Rancher candy.

But most importantly, I learned that the soldier filling the sandbags and creating gravel walkways is just as vital to the operation as the soldier in the cockpit of an Apache.

On to Tirana

By Richard Roesler

As our Macedonian taxi driver turned and high-tailed it back to Ohrid, Stripes photographer Mark Allen and I gazed over 300 yards of no-man’s land at the border into Albania.

The Albanian border checkpoint consisted of a crumbling concrete structure, stripped of many of its electrical fixtures and tile. Soldiers with battered AK-47s — clips in the magazines and breech-bolts stained from recent firing — stared at the two of us as we humped our gear and bags over to the building in the rain.

Inside, soldiers lounged around a pot-bellied stove in a concrete room, the walls and teapot stained with soot, and a single dim light bulb hanging from a frayed wire in the middle of the room. Everyone was smoking. For $45 apiece, we got visas stamped in our passports and were shooed out the door, where another Stripes reporter, Kevin Dougherty, was waiting with an Albanian taxi driver anxious to get back to Tirana before dark. After dark here, the roads are not safe.

Of course, they’re not so safe during the day, either. Albanian roads are a study in potholes, steep dropoffs and the occasional truck or donkey stopped in the middle of a steep curve.

Police with AK-47s frequently stop cars on a whim and shake down the occupants for cash. We were stopped three times on the drive, and dodged the required bribe by flashing our passports and saying “Gazatar Amerikan!” or “American journalist.”

After four hours of lurching and bouncing down through the mountains in our driver’s old Mercedes, we arrived in darkness at Tirana. We eventually got rooms at the Dajti Hotel, a wrinkled grande dame of a hotel that was apparently the place during the decades of communist rule.

The Dajti still exudes some of that decaying-empire charm — high ceilings, marble balconies, a lobby of mysterious people lounging about, smoking, and talking quietly with each other. Regrettably, the infrastructure hasn’t changed much since an Italian tourism company built it in 1935. Bathroom fixtures are missing, rooms are apparently never vacuumed, and the hot water goes off at night. In our original rooms, the showers were literally a tiny trickle of water. I finally had to cut two water bottles in half and use those to bathe.

Outside the hotel doors, the streets are filled with moneychangers waving fistfuls of Albanian lek bills. Taxis and trucks keep up a constant serenade of horns, and the sidewalks, cafes and streets are full of-men in worn sport coats, smoking and drinking coffee. There are few jobs here, and the overall impression is of an entire nation of people loitering, waiting for something to happen.

In the cooler dusk, Tirana’s boulevards fill with pedestrians — men walking arm in arm, laughing girls, families with a child sitting on dad’s shoulders. Old men in porkpie hats squat together and smoke.

“These people don’t have work, but they have enough money for an ice cream or a coffee,” observed a stateside newspaper reporter one evening. “They have just enough to keep them happy.”

The war seems very distant, seen only on Italian TV programs, in the screamer headlines of the Albanian press and in the street graffiti that pops up overnight: “UCK,” or Ushtria Clirimtare Kosoves; the Albanian name for the rebel Kosovo Liberation Army. Not surprisingly, the KLA enjoys tremendous support in Albania. On a recent taxi ride from the NATO compound at the airport back to Tirana, the taxi driver apologized and pulled into a gas station to drop off what looked like brand-new military tactical radio phones from his trunk. When asked where the phones came from, all he would say is that they were for the KLA.

For the first time in memory, hotel clerks say, hotels are booked up, mostly with reporters and photographers. The battered Mercedes sedans that rule the streets have been joined by military vehicles from several countries, food trucks and tough-looking four-wheel-drive Land Rovers and Defenders belonging, to news crews and the dozen or more humanitarian relief agencies working here.

At night, though, comes the most poignant reminder of the war being waged in the north. After dark, when the chances are best of getting an international call out on Albania’s overwhelmed and archaic telephone system, long lines of people form at pay phones throughout the city. They wait patiently, silently, in queues that stretch across the sidewalk and into the dirty streets.

These are people who fled Kosovo, and are spending what little money they smuggled out in baby blankets or shoes or underwear or telephone cards to contact family.

And at night, Tirana’s honking horns and street chatter settle down, and fall silent, except for the occasional rattle of a stolen Kalashnikov rifle someone is firing just for the hell of it.

And as the city sleeps in the darkness, the refugees wait, silently in their lines at the pay phones, the ones in the front cradling the receivers and listening intently for a voice on the other end.