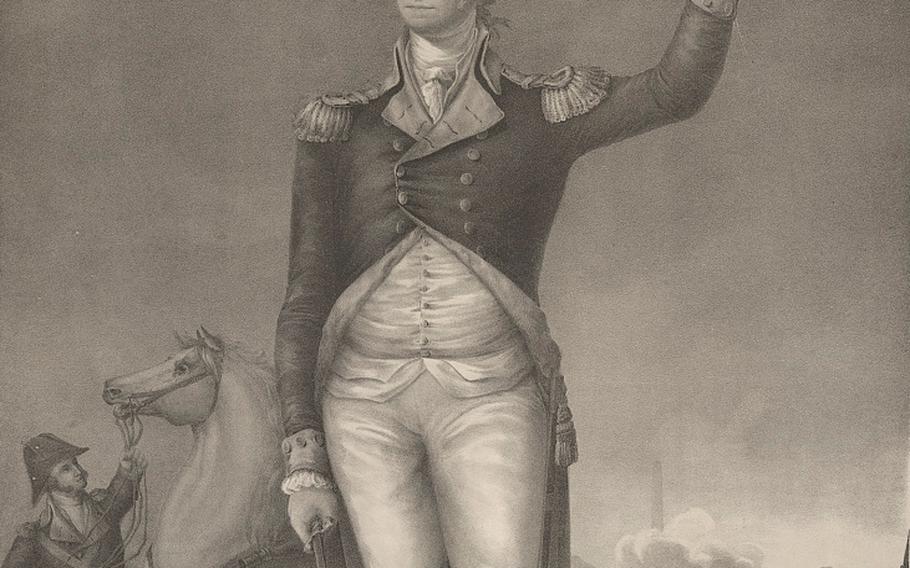

A cropped version of a print showing George Washington in his military uniform. (Library of Congress)

We all know the familiar stories about George Washington. The cherry tree he chopped down. (Except he didn’t.) The lies he never told. (Except he did.) His wooden teeth. (Except they weren’t — they were ivory dentures and real teeth extracted from his enslaved workers.)

But if you read through the major biographies of Washington, you’ll find something else that pops up again and again. According to the most heralded Washington chroniclers, the first president had killer thighs.

Ron Chernow (“Washington: A Life”) fixated on his “virile form,” particularly his “wide, flaring hips with muscular thighs.” Richard Brookhiser (“Founding Father: Rediscovering George Washington”) remarked on his “well developed” thighs and quoted a bodybuilder who examined a Washington portrait and said, “Nice quads.” Joseph J. Ellis (“His Excellency: George Washington”) wrote that his “very strong thighs and legs ... allowed him to grip a horse’s flanks tightly and hold his seat in the saddle with uncommon ease.”

It drives Alexis Coe nuts.

When Coe set out to write her 2020 Washington biography, “You Never Forget Your First,” she was struck by how few biographies of the first president were written by women or people of color. Instead, they pretty much all seemed to be written by, and largely for, white men.

“Women and people of color are not considered the readers of presidential history,” she said. “And I think that’s related to this emphasis on masculinity.”

Take the fact that Washington did not have biological children. Male biographers, Coe notes, seem to bend over backward to assign responsibility not to the virile general — who, Coe believes, was probably rendered sterile by an illness in his youth — but to his wife, Martha, who actually had demonstrated her fertility by having children in her first marriage. (Chernow, Brookhiser, Ellis and their publicists did not respond to requests for comment.)

George Washington on horseback, cropped to highlight his legs which, according to one biographer, “allowed him to grip a horse’s flanks tightly and hold his seat in the saddle with uncommon ease.” (Library of Congress)

In Washington’s own time, there doesn’t seem to have been this obsession with his physique that so consumed posterity. Washington was battered by a seemingly never-ending stream of maladies — including, notably, two infections in his thigh (one of which rendered him bedridden for six weeks shortly after he became president). And his powerful horse-gripping legs appear to have failed him when he fell off his ride and had to use a crutch to get around.

In fact, Washington used his perceived infirmity to his advantage. While he was leading the Continental Army, his soldiers threatened to desert over late wages. According to Coe, Washington slipped on his new spectacles and appealed to a group of field officers, “Gentlemen, you must pardon me. I have grown gray in your service and now find myself growing blind.” They stood down, and some went years without being paid.

Washington, it should go without saying, won the Revolutionary War with his brain, not his bod. He didn’t have the superior force at his disposal, but he was a shrewd strategist and propagandist, and he led an underappreciated spy campaign. As the British spymaster George Beckwith said: “Washington did not really outfight the British. He simply outspied us.”

“I think we should talk about his body,” Coe said, “but I think we’re talking about the wrong parts.” Like John F. Kennedy and other presidents, she noted, Washington endured intense physical ordeals that informed his leadership. His bout with smallpox inspired him to inoculate his soldiers at the start of the war; that decision, Coe said, may have helped the rebel force prevail.

Presidents, like all public figures, have long had their bodies scrutinized. Not even superb physical conditioning could protect them from mockery. Gerald Ford, a college football star, was subjected to endless ridicule (including on “Saturday Night Live”) after he stumbled down the stairs of Air Force One in 1975. When Ford was a congressman, Lyndon B. Johnson derided his mental acuity by saying he had “played football too long without his helmet.” It’s hardly new, or surprising, that critics of President Biden are making a campaign issue of his age, memory and perceived frailty. A fixation on presidents’ bodies goes all the way back to the first one.

So did Washington actually have exemplary thighs? Coe doesn’t love the line of inquiry. But “if I must answer that question,” she said, his thighs “were quite fine, but I don’t think they were the best of the era. The founders all had lovely parts. My favorite would be their service.”

Aaron Wiener is an assignment editor on the Metro desk, working across all teams but focusing on Retropolis, The Washington Post’s history vertical. Before joining The Post, he worked as a senior editor at Mother Jones, a reporter at Washington City Paper and a Berlin correspondent for the Los Angeles Times.