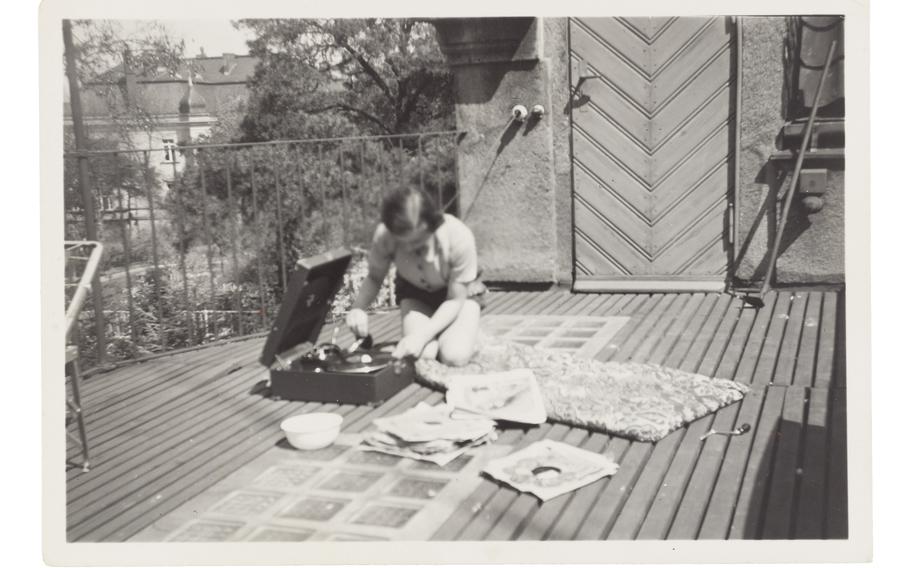

Felice Schragenheim with a record player on a terrace in Berlin in 1934. (Jewish Museum Berlin; gift of Elisabeth Wust)

Elisabeth “Lilly” Wust was a mother of four and the wife of a Nazi soldier. Felice Schragenheim was a Jew who worked undercover at a Nazi newspaper, smuggling out valuable information to the Jewish underground. The attraction between them was immediate. Nothing could extinguish their love — not even Hitler’s war machine.

Felice was just 16 at the time of the Kristallnacht pogrom of November 1938, in which synagogues were burned and tens of thousands of Jews were carted off to camps. She was a bright student, but as the last “full Jew” in her class, she was expelled from her Berlin high school. Soon, Jews were barred from public theaters. Felice’s family was ousted from their home.

Lilly Wust met her husband in 1933 — the year Hitler became chancellor of Germany. She had no shortage of men while her husband, Günther, was on the front lines, and involved in his own dalliances.

But it would be Felice who would stoke “all the fire in my heart,” Lilly later wrote.

The two first crossed paths on Nov. 27, 1942, when the red-haired, freckled Lilly, 29, went with her housemaid, Inge Wolf, to meet a friend of Inge’s at the Cafe Berlin. The friend was 20-year-old Felice, an elegant brunette in a rust-red suit, her long legs wrapped in silk stockings. Lilly had no idea that her new acquaintance was secretly Jewish.

Felice soon joined Lilly and Inge at the Wust home for dinner — a meal they could have thanks to rations Lilly received for her gentile children. One meal led to another, and before long, a group of Felice’s free-spirited friends were descending on Friedrichshaller Strasse 23. Felice played banned French songs on her record player while Lilly served bread with cold cuts and eggs. Often, Lilly was left guessing who was sleeping with whom.

Lilly didn’t ask many questions — about affairs or Felice’s whereabouts. Felice continued to keep her Jewish identity secret. A few years earlier, her family had begun planning to immigrate to Palestine; her uncle, a doctor in the United States, had also applied for a visa to bring Felice to America. But soon Western European countries would close their borders, and when war broke out, passage to the United States would become nearly impossible.

At the Wust residence, Lilly found her husband kissing Inge. Dazed, she headed for the kitchen, where Felice tried to draw her into a kiss. Lilly pulled away. For two days, they pretended nothing had happened.

Meanwhile, the Nazis’ Final Solution was underway. Trucks of Waffen-SS abducted Jewish workers from factories. Allied bombs fell on Berlin, and the Wusts hid in shelters. Felice stayed with friends in the mountains. But the two women’s connection only deepened; they had agreed to think of each other every night at 9 o’clock. Their romance continued to blossom through correspondence while Lilly was hospitalized for a jaw infection.

“… Felice, when will we be alone, completely alone? … I’m still sick — but afterward — finally we will fall into each other’s arms, and in the whole world there will be only you and me.”

On Lilly’s ninth wedding anniversary, her husband appeared at the hospital with flowers. The distance between husband and wife was evident. Felice arrived that evening and bent over Lilly’s bedside, her hair brushing against Lilly’s cheek. Lilly surrendered to her kiss.

“Felice, if you knew how my heart was pounding at this moment! … Tomorrow, I will be relentless. … When is our wedding day to be?”

Felice was struggling to evade the Nazi apparatus. Already, it had been two years since Jews were forced to wear the yellow star, and Felice hid in plain sight while Jews were deported on freight trains. Her grandmother was among those rounded up and sent to their deaths.

Felice Schragenheim on a blanket in the countryside of Berlin. Date unknown. (Jewish Museum Berlin; gift of Elisabeth Wust)

The story of Felice and Lilly’s unlikely, passionate affair is captured in the 1994 book “Aimée & Jaguar: A Love Story, Berlin 1943,” by Erica Fischer, who interviewed Lilly when she was 80. In 1999, it was made into the German film “Aimée & Jaguar” — the nicknames they gave each other.

When Lilly was back home and Felice slipped into bed with her, Lilly told Fischer, “I now knew who I was, where I belonged, to whom I belonged; everything else was totally unimportant to me.”

As Jews were being shipped to Auschwitz and the Theresienstadt transit camp, Felice moved in with Lilly, who shocked her husband by bringing up divorce.

Felice continued to disappear for days on “business trips.” The mystery of her whereabouts ate away at Lilly, who demanded answers. Felice finally gave in.

“Promise me that you’ll still love me,” she said, then added, “Lilly, I’m a Jew.”

Astonishment gave way to understanding. “And now more than ever,” Lilly responded to Felice’s plea. She paid no heed to her own precarious position, wanting only to save Felice.

They slept in late on Sundays. Lilly worked at the sewing machine, trimming dresses for Felice. Lilly began to contemplate the prospect of a life with four children, little work experience and no husband.

“What is love, tortuous happiness, glorious pain?” Lilly wrote on the back of expired food coupons. She saved copies of all her correspondence to Felice.

Lilly composed an unofficial “marriage contract” on June 26, 1943. One month later, the Gestapo ordered confiscation of the assets “of the Jewess” Felice Sara Schragenheim. Felice had offers to escape with associates. Lilly considered leaving her children temporarily in a “safe home” and following Felice into exile. Felice, Inge and a friend debated crossing the border into Switzerland, but they ultimately decided Felice was safer in Berlin.

It would be Felice’s last chance to leave Germany.

That Christmas, Lilly wrote to Felice, “I have such hopes for the coming year, above all, finally to have a quiet life.” By 1944, even as Berliners were sweeping debris from bombed-out houses, Felice had seemingly lost all sense of danger, sneaking into the news office at the National-Zeitung to gain intel that might help others escape the Final Solution.

On Aug. 21, 1944, a hot summer’s day, the couple biked to the Havel River to swim. Lilly’s children were in the care of a friend for the day. Felice brought her old Leica camera. They set the timer and took what would be their last photos together.

The Gestapo was waiting at Lilly’s apartment when they returned.

Felice dared to flee, bounding downstairs to hide in a neighbor’s apartment. She was betrayed by another neighbor. The Nazi police pulled her from under a couch, kicked her and dragged her down the stairs.

Lilly was left in her children’s room, screaming and crying. She soon gathered the courage to try to find her beloved.

Lilly learned that Felice was in a Jewish hospital that had been converted into a collection camp. She discerned the right building by its barbed wire and insisted to the guards that Felice be summoned. Armed with French cigarettes as bribes, Lilly began paying regular visits with fruit and tomatoes for Felice, who now wore a yellow star on her chest.

Lilly wrote in her diary on Aug. 26:

“You shall read this diary when you are no longer the “Jewess Schragenheim,” but a person among other persons. Dear God, let us live together or die. Do not allow for only one of us to survive. I will never get over not seeing my Felice again. Never in a lifetime.”

Felice and Lilly saw each other for the last time on Sept. 7. They were allowed half an hour together. Lilly gave Felice a lock of her red hair, which Felice wrapped around her comb.

The next day, Felice was taken to Theresienstadt.

Remarkably, they managed to exchange some letters. But within a month, Felice was in a cattle car bound for Auschwitz — then onward to the Gross Rosen and Kurzbach concentration camps. Felice contracted scarlet fever and landed at a hospital in the town of Trachtenberg before meeting her fate either during an eight-day death march or at the Bergen-Belsen camp.

Lilly spent years writing in her diary, which she called her “Book of Tears.” She believed it would one day be all that was left of their love. She joined the Jewish community after the war and sent her children to Jewish schools. Her son, Eberhard, immigrated to Israel in 1961. Lilly felt at home during her visits, and she kept the scarf she wore to Jerusalem’s Western Wall in the same bag where she stored the negatives of the Havel River photos.

But she could never find joy after Felice died. She stored her journals and Felice’s documents, photos, letters and poems in two suitcases and carried the keys to them around her neck. She wore a gold wedding ring engraved with “F.S.” and a silver ring with a green stone that she had given to Felice — which Felice gave back just before the Gestapo dragged her from Lilly’s apartment.

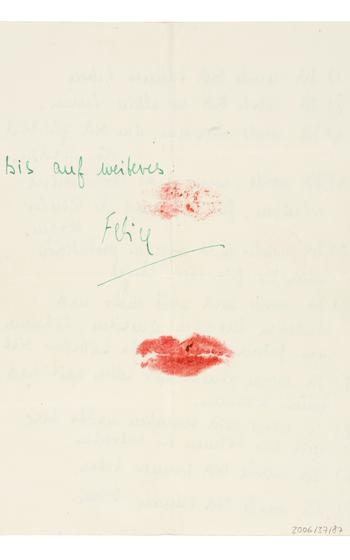

Lilly died in 2006, and on her gravestone Felice’s name is etched in memoriam. The Jewish Museum in Berlin holds many of their artifacts, including love letters and the marriage contract, which bears an imprint in red lipstick — sealed with Felice’s kiss.

Margaret Hetherman is a Brooklyn-based independent journalist and essayist.

The last page of a 1943 unofficial marriage contract containing Felice’s vows to Lilly, sealed with Felice’s kiss. (Jewish Museum Berlin; gift of Elisabeth Wust)