Edward Dwight Jr. left his home in Kansas City, Kan., in the early 1960s to become one of the nation’s first Black astronauts. Racism and politics soon crashed that ambition. His story is told in a new film, “The Space Race.” (Screengrab from The Smithsonian Channel)

(Tribune News Service) — Edward Dwight Jr. left his home in Kansas City, Kan., in the early 1960s to become one of the nation’s first Black astronauts.

Racism and politics soon crashed that ambition.

“It was hell and it really turned me upside down,” says Dwight, now 90, who had already faced the scourge of racism while growing up in KCK. “They tried to make me fail out and make it seem like I was ignorant and didn’t have the intelligence to be an astronaut.”

With a change in presidential administrations came a change of plans, and the program to put Black men in space was scuttled. Dwight, who had been a pilot and aeronautical engineer, went on to become an acclaimed painter and sculptor. And the nation would not have its first Black astronaut until 1983.

The stories of Dwight and other Black pilots, scientists and engineers in the space program are in the spotlight with a new National Geographic documentary, “The Space Race.” It premieres on Disney+ on Feb. 12. But Kansas Citians got an early glimpse of it last month at the Zhou Brothers Art Center, 1801 E. 18th St. It will be screened again at 7 p.m. Feb. 22 at the Gem Theater.

“It’s just a lot that we didn’t know that this film brings out,” says William Wells, who organized the Kansas City screenings. “Then it connects the social struggles that we face here on this earth and how we had to basically put ourselves in space looking toward a better future without boundaries and limits.”

Wells is founder and executive director of aSTEAM Village, a Kansas City nonprofit that encourages kids to become engineers.

“How many minds would have looked to the stars as their environment or domain of occupation? I think that’s the question,” he says. “It’s systemic that we have had these barriers to keep us where we were and never given the opportunities or the same access and opportunity to compete on a fair playing field.”

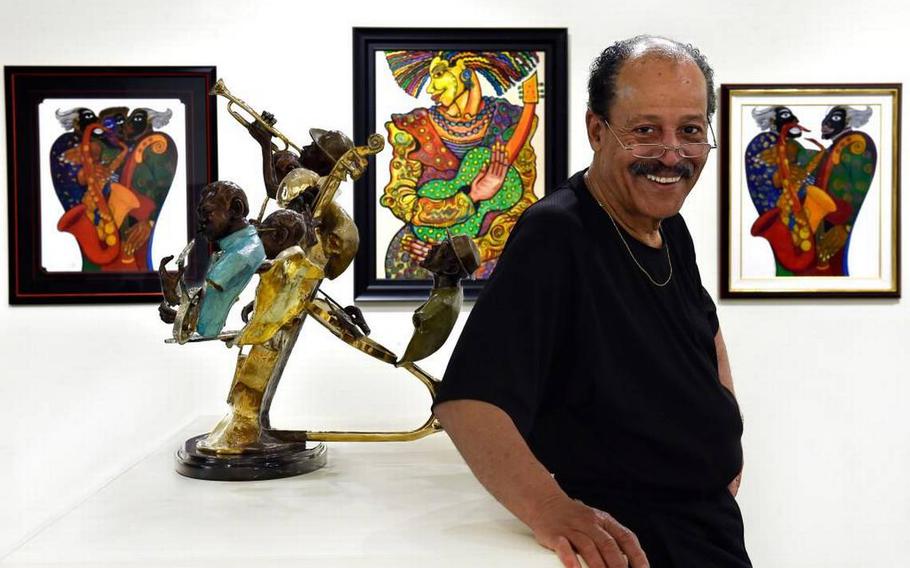

Ed Dwight in 2016, with his bronze sculpture on display at the American Jazz Museum. Behind Dwight are the paintings of Charles Biggs. (Rich Sugg, The Kansas City Star/TNS)

Educated in Kansas City, Kan.

Dwight became obsessed with the sky as a child, during late-night walks with his mother near the old Fairfax Municipal Airport, learning about the planets and constellations.

“I got this education of lunar science from my mom before I was 5 years old,” Dwight says by phone from his adopted city of Denver. “Later when I got into the space program and started lunar astrology and stuff, I was like, I learned all this when I was a kid.”

His father and namesake played baseball with the Kansas City Monarchs. His mother was a college-educated woman who wanted to make sure her son had the best opportunities at life.

In addition to her nightly lessons on astronomy, she also used every opportunity to teach her son about plants, animals and perhaps most importantly for his future, art.

She petitioned the Vatican to allow her to send Dwight and his sister to Bishop Ward Catholic High School, which was then segregated. He became the first Black man to graduate from there in 1951.

Dwight learned that the only tool at his disposal to fight prejudice was excellence. On his first day of class, he recalls, 300 students left school in protest.

“They thought they were going to get this big robust Black guy who was going to rape their daughters,” says Dwight. “I was getting my butt kicked on the way to school every morning the first year, but there was nothing these white folks could say because we were doing things and we were rock stars.”

Through his accomplishments in academics, athletics and art, he says tensions began to ease. Eventually, students and teachers accepted him as an example of the merits of a Catholic school education.

After high school, Dwight earned an associate’s degree in engineering in 1953 from Kansas City Kansas Junior College (now Kansas City Kansas Community College).

Dwight’s future would forever change after he saw a picture of Dayton Ragland, a Black Air Force pilot from Kansas City, on the front page of The Call newspaper.

“Growing up by the airfield, I always thought flying was really fascinating but I never thought of myself flying,” says Dwight. “When I saw that picture of that Black pilot, I said to myself, they are letting Black folks fly airplanes. And I went straight to the recruitment office and told them I want to fly. They told me to get out of there.”

He remembered his mother’s perseverance to get him into a segregated high school. Taking a page from her book, he wrote a letter to the Pentagon.

Dwight received confirmation that Black pilots were being accepted into flying programs, and in 1953 he enlisted in the Air Force and joined 33 other Black recruits.

He reached the rank of captain and in 1957 graduated cum laude with a bachelor’s degree in aeronautical engineering.

The space program lifts off

In 1959, when John F. Kennedy was campaigning for president and seeking the Black vote, he met with Whitney Young of the National Urban League to discuss plans for a Black astronaut. The pilot would have to be under 30, with a stellar service record and 1,500 hours of fighter pilot time.

The program became a reality. Dwight applied and was told he was being considered. But he was apprehensive.

“I was not interested in being a Black astronaut,” says Dwight. “I was very happy doing what I was already doing and had no idea what they had planned and had no interest.”

But his mother told him to take the opportunity to break down racial barriers and inspire the next generation. He spent the next 13 months training at the Aerospace Research Pilot School. He recalls a white recruit telling him they were instructed not to speak with him or eat with him.

Dwight’s progress came to a halt, however, in 1963, when Kennedy was assassinated, and the Johnson administration wanted to start over from scratch on many Kennedy initiatives, he said.

“Everything was fine until the president got assassinated,” says Dwight. “Then I lost my sponsor. President Johnson brought me into the White House, explained to me how he had to have his own Black astronaut. That’s when the politics and the fighting really got started and everything was in a free fall. The president asked me to help him find my replacement and stop making speeches around the country. Stand down for now and right after we fly your replacement in space, then we’ll bring you back in. I didn’t hear anything, so I quit.”

He was disappointed that his space career never took off. But what bothered him the most was the indifference shown by the Black community over the broken promise. Finally, Guion “Guy” Bluford — the nephew of Call publisher and Kansas City civil rights leader Lucile Bluford — went into space in 1983.

“I think the important part is it opened the conversation of Black people in space,” Dwight says. “It took them 20 years to fix things and get Black astronauts into space, and the community is coming around now. But back then, the sentiment was why are you spending all this money to put people in space when you have issues down here?”

Wells believes that the Black community of the time saw Dwight’s appointment to be a symbolic gesture that would not help advance Black people.

“I think at the end of the day,” says Wells, “this is us realizing that we have to come together and we do have to work harder sometimes to get where we need to go.”

Instead of becoming bitter, Dwight pivoted to a life of art. He made a name for himself as an accomplished sculptor, with his space dreams slowly fading. He is happy for this new generation learning his piece of Black history and hoping that people walk away with an understanding that sometimes it isn’t about being first, it is about doing your best.

Dwight’s sculptures and paintings depict a range of Black culture, such as historical figures, monuments and jazz. For example, Dwight’s Concerto, a brass and stainless steel sculpture commissioned in 1989, can be viewed at the Folly Theater, 300 W. 12th St.

Already, Hollywood has helped educate about Black Americans’ role in the space program with the Oscar-nominated “Hidden Figures,” co-starring another Kansas City, Kansas, native, Janelle Monae.

“There is a reason those women from the ‘Hidden Figures’ movie are just now getting learned about,” says Dwight. “I think in the past some people only could see us as entertainers or athletes. This new generation is finding appreciation for the less flashy jobs like mathematicians, engineers and scientists who also had to fight to break through.”

See the movie

“The Space Race” premieres on Disney+ Feb. 12.

©2024 The Kansas City Star.

Visit kansascity.com.

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.