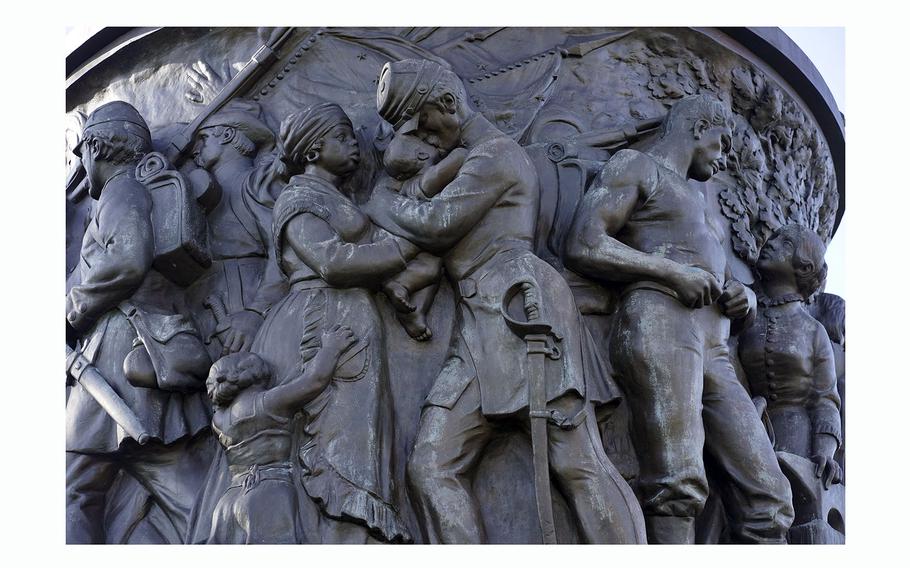

An enslaved woman is depicted on the Arlington National Cemetery's Confederate Memorial. (Bonnie Jo Mount/The Washington Post)

The U.S. Army intends to remove a Confederate memorial from Arlington National Cemetery next week as part of its ongoing work to rid Defense Department property of divisive rebel imagery, defying dozens of congressional Republicans who have vociferously protested the move.

A woman representing the American South, standing atop a 32-foot pedestal, lords above most other monuments within America’s most revered resting place. It portrays, according to the cemetery’s website, a “mythologized vision of the Confederacy, including highly sanitized depictions of slavery.”

This month, 44 Republican lawmakers cautioned Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin, the first African American to hold the post, that the Pentagon would overstep its authority by removing the memorial and they demanded that all efforts to do so stop until Congress works through next year’s appropriations bill. The memorial “commemorates reconciliation and national unity,” not the Confederacy per se, the group led by Rep. Andrew S. Clyde (Ga.) claimed.

The Army, which operates Arlington Cemetery, informed lawmakers Friday that it would proceed with the monument’s removal, officials told The Washington Post, because it was required by the end of the year to comply with a law to identify and remove assets that commemorate the Confederacy. A congressional commission had previously decided the memorial met the criteria for removal. The task will cost $3 million.

These officials spoke on the condition of anonymity due to the sensitivity of the issue. They said out of an abundance of caution that security at the cemetery would be enhanced when the work begins in coming days.

Workers will remove the memorial’s bronze elements and leave its granite base in place to avoid damaging nearby gravesites, officials said. The Army is coordinating with the state of Virginia and the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, a federal agency, for its relocation.

“We want to make sure that it is situated within an appropriate historical context,” a senior Army official said.

Virginia Gov. Glenn Youngkin (R) is disappointed by the monument’s removal, said Macaulay Porter, a spokesperson. Youngkin plans to relocate it New Market Battlefield State Park, which would be a “fitting backdrop” for the memorial, Porter said. The site is about 100 miles west of Arlington. It is unclear when that process would happen, but Army officials said the memorial will be moved to a storage facility for some time.

Removal of the memorial was recommended by a bipartisan congressional commission appointed after the police murder of George Floyd in 2020 was followed by a wide-scale reckoning with the nation’s history of racism, and it marks a significant moment in the Defense Department’s mission to cleanse the U.S. military of Confederate iconography.

The commission found about 1,100 assets that commemorate the Confederacy, including base names and street signs, and advised the Pentagon on what should be removed or changed. The memorial at Arlington was the last significant item on that list, Army officials said, and its ouster comes just before the Jan. 1. deadline set by Congress.

A spokesperson for Clyde did not immediately return a request for comment.

The Lost Cause movement, which recast rebel traitors as morally righteous warriors defending states’ rights and spread the false belief that slavery was benevolent, is evident in the memorial’s bronze panels. A weeping Black woman, described by cemetery historians as a stereotypical “mammy,” clutches the baby of a White officer, and a camp servant dutifully follows his enslaver toward battle.

The memorial’s Latin inscription directly references the idealized mythology of the Lost Cause, the cemetery’s historians say, further underscoring the deliberate historical distortion.

The marker was erected in 1914, part of a constellation of Confederate markers that rose throughout the early 1900s to cement the ideals of white supremacy as Black Americans demanded equal rights.

That context must be understood, said Ty Seidule, a retired Army general who was the vice chair of the congressional commission that recommended the monument’s removal from Arlington. While Republican lawmakers described the marker as an ode to reconciliation, it was installed in what was then a racially segregated cemetery and molded in celebration of an emerging racial police state in the South.

“It’s incredibly ironic the party of Lincoln is the one doing this,” said Seidule, a historian and visiting professor at Hamilton College, describing the GOP effort to stop the marker’s removal. “It is the cruelest monument in the country because it is so clearly proslavery.”

Workers will install safety fencing around the memorial before its removal begins, Army officials said. Protests are not permitted within Arlington Cemetery, and anyone who carries out such an action will be removed by law enforcement, they added.

After the marker’s removal, the cemetery’s staff will develop a plan for signage intended to address and contextualize the bare pedestal.

Other groups have tried unsuccessfully to keep the memorial at Arlington. A lawsuit in federal court against the U.S. military alleged that the decision to bring it down was made without sufficient public input. That suit was dismissed Tuesday, according to court filings. The Army said it did not anticipate another legal challenge before work begins next week.

In 2017, after the white nationalist violence in Charlottesville that claimed the life of counterprotester Heather Heyer, descendants of the memorial’s sculptor, Moses Jacob Ezekiel, told The Post they wanted the monument removed.

The monument glorified the fight to protect slavery, they wrote. “Take it out of its honored spot in Arlington National Cemetery and put it in a museum that makes clear its oppressive history,” the family said.

The memorial’s impending removal comes after the Army stripped the names of Confederate officers from nine installations, replacing them with several minority and female soldiers who have been unrepresented among celebrated troops for centuries. The facilities were previously named with the help of segregationists who held sway in the Jim Crow-era South and were all in states that joined the Confederacy.

Hope Hodge Seck contributed to this report.