In 2014, 24 Hispanic, Jewish and black men who had been denied the nation’s highest commendation for combat valor received long-overdue recognition. Top, from left: Vietnam War veterans Sgt. 1st Class Jose Rodela, Staff Sgt. Felix M. Conde-Falcon and Korean War veteran Pfc. Leonard Kravitz. Bottom, from left: Vietnam War veterans Spc. 4 Santiago J. Erevia and Staff Sgt. Melvin Morris. (The White House)

This article first appeared in the Stars and Stripes Global edition, March 18, 2014. It is republished unedited in its original form.

WASHINGTON — Spc. Santiago J. Erevia had orders to tend the wounded while the rest of the platoon pressed on attacking. But when he and the men under his care came under fire from four nearby Viet Cong bunkers on May 21, 1969, Erevia didn’t dive for cover.

Instead, he gathered up spare weapons and ran into a storm of bullets.

He knocked out one bunker after another with hand grenades as gunners in the others fired on him. Out of grenades and with one bunker still active, he took an M-16 in each hand and charged, shooting down the last defender at point-blank range.

“Having single-handedly destroyed four enemy bunkers and their occupants, Specialist Fourth Class Erevia then returned to the soldiers charged to his care and resumed treating their injuries,” reads Erevia’s citation for the Distinguished Service Cross he was later awarded.

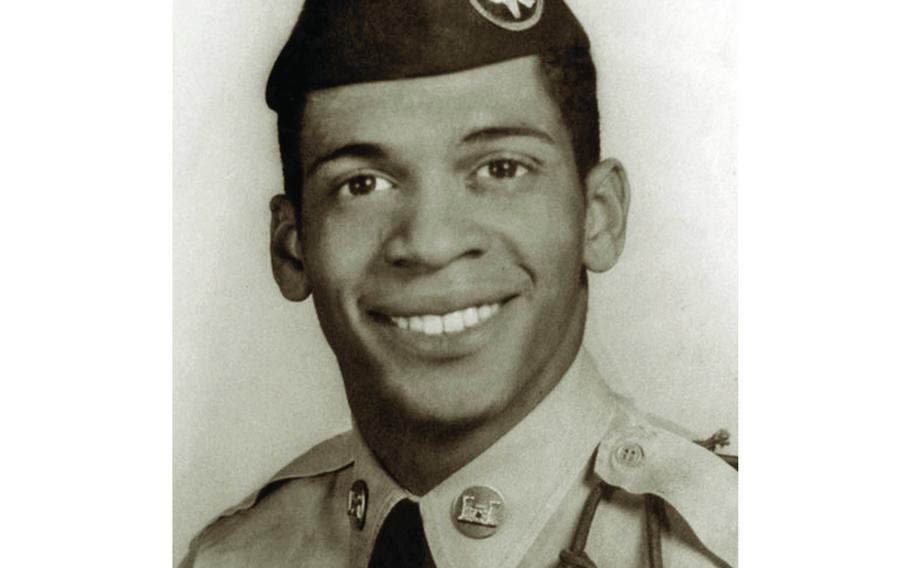

Vietnam War veteran Spc. 4 Santiago J. Erevia, of San Antonio, 101st Airborne Division (Airmobile). (The White House)

In a White House ceremony Tuesday, the United States will officially acknowledge that the selfless combat heroics of 24 soldiers, including Erevia, always merited more than the nation’s second-highest medal for valor.

Obama will present the Medal of Honor to Erevia and two other living recipients — former noncommissioned officers Melvin Morris and Jose Rodela. He’ll present it posthumously to another 21 soldiers killed in battle or who died before they could receive the distinction they had earned.

Because of the politics and prejudices of earlier decades, doubt has long lingered over whether Hispanic-Americans or Jewish- Americans had been given equal consideration with Anglo-Americans for the Medal of Honor.

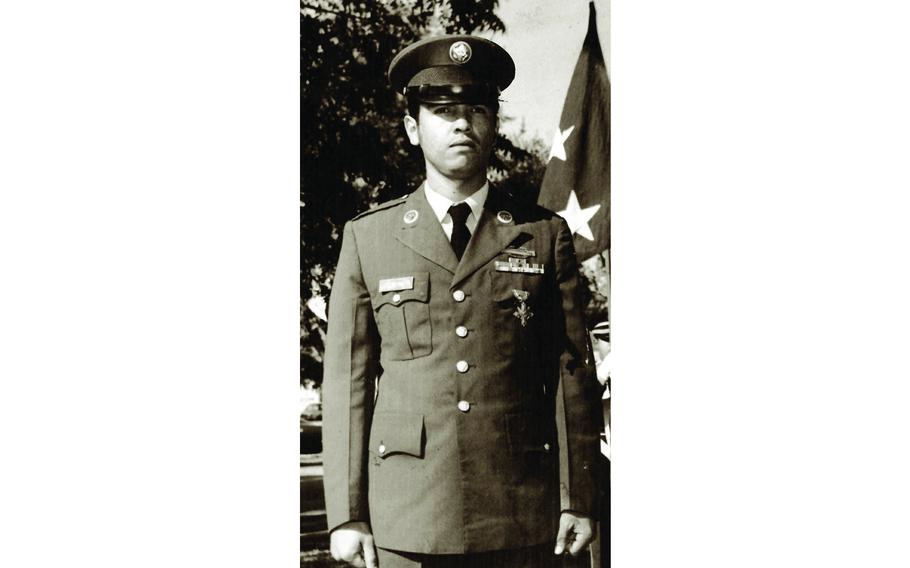

Vietnam War veteran Sgt. 1st Class Jose Rodela, of Corpus Christi, Texas, 5th Special Forces Group (Airborne). (The White House)

So in the 2002 National Defense Authorization Act, Congress ordered the Army review the cases of all Jewish and Hispanic soldiers who had received the Distinguished Service Cross from World War II onward to see if their heroism actually merited the nation’s highest award.

Army researchers combed through some 6,500 Distinguished Service Cross awards and zeroed in on 600 that went to soldiers who might be of either background. In the end, the Army singled out 19 Jewish and Hispanic soldiers who deserved the Medal of Honor, along with five soldiers of other backgrounds.

The action echoed an earlier review ordered in 1996, which found seven black soldiers deserved the Medal of Honor for actions in World War II. Before that, there were no black recipients of the medal for that war.

Vietnam War veteran Staff Sgt. Melvin Morris, of Oklahoma, 5th Special Forces Group (Airborne). (The White House)

‘I will get the body’

Among the deserving soldiers found in the latest review was former Special Forces Staff Sgt. Melvin Morris, a black man who had been awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for action on Sept. 17, 1969.

Morris was commanding a strike force in the Mekong Delta when he received word that the commander of another team had been killed near an enemy bunker.

“That body has to be recovered because we can’t leave him behind,” he said in an interview. “I made a decision right then, I will get the body.”

He and two volunteers reached the fallen sergeant, and Morris said a brief prayer just as a burst of enemy fire wounded the other two men.

Morris helped evacuate them, and with two more men, brought back the body of his fallen comrade. But then he was forced to return a third time because he realized an important map case had fallen from the dead sergeant’s pocket. On his third dash back into the danger zone, flinging grenades wildly, his luck ran out and he was shot three times — in the chest, right arm and left hand.

Despite his wounds, Morris — who’d ordered his men not to attempt to rescue him if he fell — fought his way back to his strike force and was taken out by a medevac helicopter.

During an attack in the Vietnam War, Staff Sgt. Felix M. Conde-Falcon destroyed four enemy bunkers and was targeting a fifth before he was shot down by the enemy. (The White House)

Fight to the finish

A number of the men who’ll be honored Tuesday never made it out of the battles in which they distinguished themselves for bravery.

Staff Sgt. Felix M. Conde-Falcon was killed after mounting a devastating assault on a bunker complex on April 4, 1969. After assaulting and destroying several bunkers with grenades, he attacked a fourth bunker singlehandedly with a machine gun, killing the enemy inside, according to his Distinguished Service Cross Citation.

Out of ammo, he picked up an M-16 and zeroed in on a fifth. A few meters from his goal, he was shot and killed.

In the Korean War, Pfc. Leonard Kravitz took over for a wounded machine gunner and shot down a column of advancing Chinese forces before he was killed by gunfire. (Unknown)

Fearless and deadly

Pfc. Leonard Kravitz sacrificed himself for his fellow soldiers during brutal fighting on the Korean peninsula on March 7, 1951.

After the machine gunner he was assigned to assist was wounded, Kravitz took over the job, “and poured devastating fire into the ranks of the onrushing assailants,” the citation for his Distinguished Service Cross read.

That was his job. But then, as the tide of onrushing Chinese forces overwhelmed the American defenses, the order came to fall back. Kravitz, however, voluntarily stayed at his position and mowed down an entire column of enemy troops moving toward an American position.

His marksmanship allowed the Americans to escape, but his fearlessness in the face of attack ultimately cost him his life. When the Army retook the position, the Jewish machine gunner’s body was found next to his gun.

More than six decades later, the Army and the nation are finally ready to affirm that Kravitz and the 23 other honorees Tuesday long ago proved themselves heroes of the highest caliber.