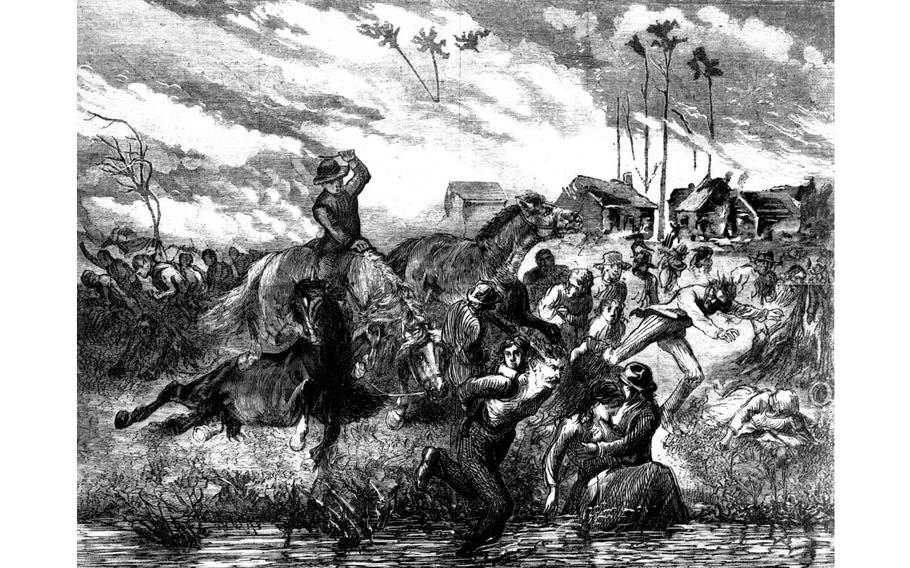

An illustration showing people seeking refuge in the Peshtigo River from the 1871 Peshtigo Fire. (Peshtigo Fire museum/Wikimedia Commons)

In October 1871, the blaze that would become America's deadliest forest fire arrived in the lumber town of Peshtigo, Wis., with a roar that sounded like a freight train. Then, everything seemed to happen at once. "Countless fiery tongues" whipped down from the sky, fire blasts came "from every side," according to a retelling in the New York Tribune. There was "no beginning to the work of ruin," the newspaper's correspondent wrote. "The flaming whirlwind swirled in an instant through the town."

Similar to last week's fires that ripped through the island of Maui, in Hawaii, killing at least 106 people and razing the historic town of Lahaina, the 1871 Peshtigo fire was amplified by extreme winds and an unusually dry season that primed vegetation to spread the blaze. The fire ravaged the Wisconsin town rapidly. "It rained fire; the air was on fire," one survivor wrote in a letter. "Some thought the last day had come."

For many, it had. In an hour, the town of Peshtigo is said to have been virtually wiped off the map. It is estimated that some 1,200 people died — 800 in Peshtigo alone — as the fire blazed through 17 towns on both sides of Green Bay, burning more than a million acres.

Despite the mass destruction, America's most lethal wildfire has long been overlooked, overshadowed by the Great Chicago Fire, which erupted that same night in 1871 and consumed public attention.

As the rising death toll reported from Maui saw it become the deadliest U.S. wildfire of the past century, the devastating events in Peshtigo carry renewed significance.

Even with technological advances in firefighting systems, increasingly severe, mass-casualty fires are still occurring in the United States. The Lahaina fire is the most recent example, and before that, the 2018 Camp Fire, which killed 85.

The effects of climate change are also likely to create conditions — dry spells, more intense storms — that could worsen fires in the future, making the horrors of the past an important guide.

"I think that most people have no clue about the Peshtigo fire and it's one of the most deadly natural disasters in U.S. history," said Chris Dicus, a professor of wildland fire management at California Polytechnic State University. More than a century later, "we're doing many of the same things that we were doing back in 1871," he said, such as continuing to build with fire-prone materials in fire-prone areas.

The Maui fires have parallels to Peshtigo, he said. "Whether it's Peshtigo, Black Saturday in Australia, or the Tubbs Fire in Sonoma County, California, there were extreme winds that pushed the fire very rapidly through dry grasses," he said, referring to historic blazes in 2009 and 2017. "When it hit the towns, it was just building-to-building spread."

These severe fires were also worsened by a lack of communication. "Many people had no idea that there was even a fire happening until it was right on their doorstep," Dicus said.

In 1871, Peshtigo was especially vulnerable. It had a booming lumber industry and wood was everywhere — in buildings, houses, logs stacked outside homes for the winter, even sidewalks and roads. To make matters worse, lumberjacks, farmers and railroad crews regularly set fires to clear out areas of the forest for their work, heightening the risk of uncontrolled flames.

When the Peshtigo fire came, Peter Pernin, a missionary priest who wrote the best-known account of the event, described air that was "no longer fit to breathe" and smoke that made it "almost impossible" to keep one's eyes open. As he attempted to flee, he recalled vehicles and pedestrians "crashing into each other," all struggling "in the grasp of the hurricane" and "struck dumb by terror."

The next day "revealed a picture exceeding in horror any battlefield," the New York Tribune report said. Pernin, who had survived by submerging himself in the river, reported seeing an entire deceased family "blackened and mutilated by the fire fiend."

Today, the Peshtigo fire is studied "as an example of bad forestry practices and the power of catastrophic wildfire," the Forest Service Employees for Environmental Ethics said in a newsletter.

It's tempting to see calamity as a thing of the past — before satellites could tell firefighters exactly where the flames were or helicopters could blast water from overhead.

But "we are in a challenging century when it comes to managing fire," said Tom Fairman, a Future Fire Risk analyst at the University of Melbourne. Going forward, "it has to be about how we improve 'living with fire,' " he said, noting the importance of smooth emergency communications, managing forest lands to be resilient and "wisely" applying prescribed burns.

Looking back at Peshtigo, Dicus cautions, "Not a lot has changed in the heat of the battle."

There's better equipment and technology, he said. "But when the winds come up in a very fire-prone vegetation, all bets are off and it's just everyone in survival mode."

The Washington Post's Michael S. Rosenwald contributed to this report.