The Hanford women’s baseball team was a lightning rod for FBI attention. The FBI suspected three women on the team were romantically involved, so agents secretly questioned their teammates. (Hanford History Project/TNS)

SEATTLE (Tribune News Service) — In 1943, thousands of workers began arriving at remote outposts in Washington, New Mexico and Tennessee where American ingenuity would be pressed to its limit in a secret and frantic push to build the first atomic bomb.

One particular group of eight women at Hanford in Eastern Washington and Los Alamos in New Mexico would have been among the forgotten, if not for the FBI’s feverish hunt for private details about their lives. The government that had recruited them to the elite Manhattan Project was now trying to strip them of vital security clearances by proving they were lesbians.

The Manhattan Project’s defining role in U.S. history is now in the spotlight via the newly released movie “Oppenheimer,” which chronicles the famed scientist J. Robert Oppenheimer’s work and the government’s hard-line efforts to kick him, too, out of the nuclear weapons program.

While movies and biographies spotlight Oppenheimer, thousands of others toiled in obscurity in the Manhattan Project, even as their contributions altered the trajectory of history. They were history’s extras.

Declassified FBI records and Atomic Energy Commission memos reviewed by The Seattle Times chronicle the women’s experiences trying to live their authentic lives while staying ahead of the FBI in a chase that stretched from Los Alamos to Hanford and spanned a decade. The internal memos were created in response to a 1953 presidential order barring gay and lesbian people from federal employment, which had immediate consequences.

The tale of the group, which The Times has dubbed the Manhattan Eight, was previously unknown to some of the foremost scholars of the Manhattan Project and “the Lavender Scare,” the name historians gave the government’s 1950s-era anti-gay crusade, according to Seattle Times interviews.

It illuminates a dark chapter in American history when, based on the thinnest of information or others’ perceptions, federal employees were subjected to deep surveillance of their personal activities and associations.

“Because these Manhattan Project sites like Hanford and Los Alamos are at the heart of the national security state, you can see an intense obsession with rooting out anything that doesn’t conform with commonly accepted American ideals,” said Robert Franklin, assistant professor of history at Washington State University, Tri-Cities, and assistant director of the Hanford History Project.

“I could imagine in that kind of white-picket-fence environment, the idea of anyone outside of heteronormative would’ve been subject to real persecution if they were found out.”

FBI’s most wanted lesbian

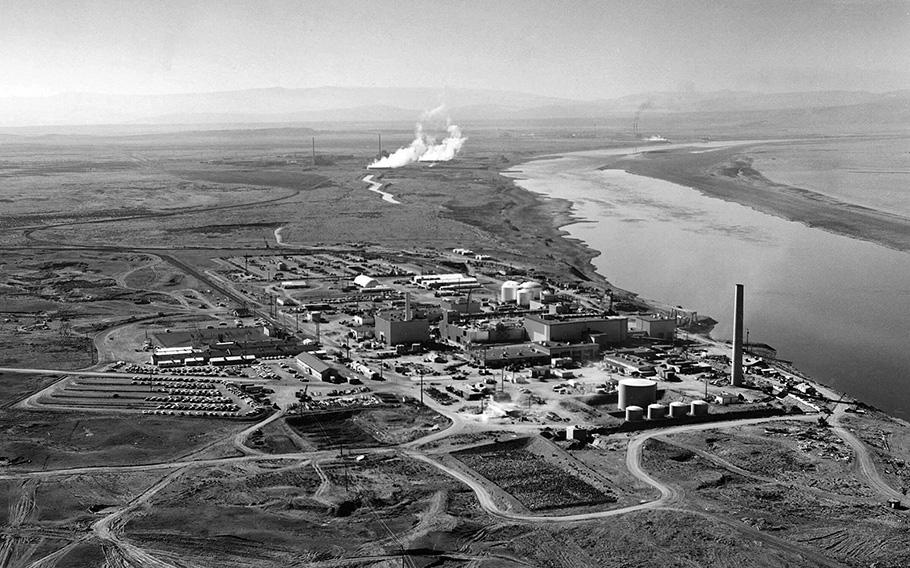

The 600-square-mile, scrub-oak-pocked Hanford site was ideal for the secret work of constructing and operating the first nuclear fuel production reactors. The chilly waters of the Columbia River were tapped to cool nuclear reactors, and the site was far from prying eyes in population centers. Plutonium fabricated there would power the first nuclear bomb detonated in the Trinity Test profiled in the movie, and the atomic bomb that devastated Nagasaki in 1945, which immediately killed at least 39,000 people.

Nuclear reactors line the riverbank at the Hanford site along the Columbia River in January 1960. The site was chosen for its isolated location and proximity to the cold water of the Columbia, which were used to cool nuclear reactors. (U.S. Department of Energy/TNS)

Hanford was quietly established in 1943, and the first inhabitants soon arrived to begin their work. Those judged fit for the project’s most secretive divisions were granted “Q” clearances, affording them access to closely guarded secrets that could only be discussed with fellow Q-level workers. Each of the Manhattan Eight got security clearances of some kind.

Inside Hanford and Los Alamos, the science hub of the Manhattan Project, secrets were currency and paranoia reigned. It was presumed everyone’s quarters were bugged. FBI agents trailed workers outside of work hours and reached into their pasts, grilling childhood acquaintances for any indication they were a security risk and could be potentially blackmailed by U.S. enemies.

“The [Atomic Energy Commission], in saying these people are going to be security risks, they’re damning them. You’re also lumping them in with groups that might wish the U.S. and its allies harm,” Franklin said. “They’re not enemies, but the fact is they could be compromised just because of who they are.”

When the FBI later peered into the lives of the Manhattan Eight, at least 16 co-workers handed over information, possibly to deflect agents’ attention from themselves.

The eight were “considered by almost everyone to be Lesbians,” according to a declassified summary of the Atomic Energy Commission file on the group, using homophobic and sexist language common to the era. “These girls were coarse and masculine looking and that they wore men’s clothing most of the time. They were seldom seen out with men and associated only with girls in their own small group.”

The commission was a secretive agency created in 1946, which preceded the Department of Energy in control of the nuclear weapons program.

The women are identified in declassified documents only by letters — A through H — without many other clues about their pasts. For clarity, The Times assigned them names based on their letter, using first names popular in the era. They might have been the Manhattan Nine, but another suspected lesbian was “terminated and escorted from [the] project” in 1947 for allegedly trafficking alcohol. A grand jury declined to indict her.

The documents, originally obtained by the government transparency website governmentattic.org under a Freedom of Information Act request, do not definitively state whether they were lesbians, but they faced consequences nonetheless.

The first of them to reach Hanford, in February 1944, was Edith, a clerk with the Army Corps of Engineers, and Claire, who began working at an unclassified job but later gained a Q clearance to become a “computer” in the plant’s transportation division for General Electric Co.

Diane arrived in 1948 and got Q clearance as a laborer in GE’s health estimate department. Initial security reviews of all three women by the FBI raised no concerns about their sexual orientation.

The five remaining members of the Manhattan Eight started their careers at Los Alamos.

Among them was Annie, who later transferred to Hanford, where her rumored affairs with women made her and her associates lightning rods for FBI attention. Based on the extent of the FBI’s focus on her, Annie may have been America’s most wanted lesbian.

She arrived at Los Alamos in November 1943, holding various posts over the next couple of years. The FBI, which had been monitoring her for years, documented its suspicions that she was a part of the group of lesbians. After World War II ended, Annie applied for an overseas transfer with the War Department along with her suspected lover, who’d also resigned from Los Alamos. They were stationed in Okinawa.

“A teletype appeared in the records of the War Department stating that it was well founded ‘on common knowledge at this installation’ that both [Annie] and an associate with whom she was traveling in Okinawa were ‘that way about each other,’” according to a declassified memo by the Atomic Energy Commission.

In late 1946, Annie left the federal War Department “by reason of resignation due to ill health” and returned to Los Alamos, then resigned again in September 1947. Her next documented stop in 1949 was Hanford, where she was hired by GE and held a Q clearance.

Annie played on the Hanford women’s baseball team with Edith and Claire. A confidential informant and several teammates told the FBI that in 1947 and 1948 “when the team traveled to various cities to play games, [Edith] had vigorous quarrels with another woman as to who would share a room with [Claire].”

“Of good repute”

During the early years of the weapons program, from 1943 to 1953, homosexuality was regarded as a less-than-ideal trait in Manhattan Project employees but not a disqualifying factor, providing some grace for lesbian and gay employees.

A group of women, recognizable by their matching bold red hats, had already been meeting weekly for years at the restaurant of a well-known Santa Fe hotel, La Fonda, where they openly discussed their lives as lesbians. They’d become known around town for their hats and loud conversations.

U.S. nuclear physicist Julius Robert Oppenheimer, then-director of the Los Alamos atomic laboratory, testifies before the Special Senate Committee on Atomic Energy. (Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images/TNS)

Frank Cotter, a former FBI agent who surveilled the Manhattan Eight, noted FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover’s agents reported to the Atomic Energy Commission the presence of lesbians at Los Alamos as early as 1947. Cotter later turned his sights on Oppenheimer himself, who lost his clearance for supporting the Communist Party.

Cotter, summarizing the FBI memos for the commission, noted Los Alamos issued “‘family-type’ housing to two lesbians … to eliminate the social and moral problem in a dormitory.”

In fact, three of the Manhattan Eight — Annie, Betty and Fran — were hired at Los Alamos for the Manhattan Project despite an FBI investigation that “contained derogatory information indicating possible homosexual tendencies,” according to a 1953 memo from Atomic Energy Commission Chairman Gordon Dean, originally from Seattle.

Fran landed on the FBI’s watchlist while in the Women’s Army Corps “because of an alleged close friendship with a lieutenant.” She later married a man employed at Los Alamos, and the commission became satisfied Fran was not lesbian after an investigation found her female friends were married, “all of whom are of good repute.”

Gertrude, who worked in Los Alamos’ scientific laboratory, got the FBI’s attention when a childhood neighbor described her as “being very mannish in appearance and not considered to be attractive to men.” But she was spared further action when an informant said Gertrude “never indulged in any kind of immoral act and lived a very clean life.”

In Betty’s case, the commission’s director of security in 1947 personally advised that FBI reports implicating her as a lesbian should not disqualify her for Q clearance. So she went about living her life, moving in with another woman in Santa Fe, where “they, as a couple, have adopted a child,” according to declassified records.

Bugged houses

The first seeds of paranoia arrived when the distinctive fedoras of Hoover’s FBI agents began appearing in droves as Los Alamos opened its badge-issuing office in 1943. It was just a couple of blocks away from La Fonda hotel in Santa Fe, where a group of lesbians stopped their regular gatherings. Their red hats stayed inside.

The FBI’s crusade to identify LGBTQ+ people in the nuclear weapons program, before it was grounds for removal, drove even civilians who were gay back underground.

“The gay culture that had been established really gets dismantled and disrupted,” said Jordan Biro Walters, author of “Wide-Open Desert: A Queer History of New Mexico,” published in February by the University of Washington Press. It holds the only public account before now of the Manhattan Eight, to whom she devoted a portion of a chapter.

Agents swarmed everywhere, lurking just beyond the fences of the Manhattan Project sites, when Ellen Bradbury Reid’s father moved his family from Tennessee to work alongside Oppenheimer at Los Alamos. Scarce housing in the secret city forced the family to live in Albuquerque, and sedans filled with FBI agents religiously trailed him on his hourlong commute.

So Bradbury Reid’s father moved his family into tents a couple of miles from the lab, within earshot of high explosive tests, until permanent housing on the site became available. There, cocktail parties were common and they followed an odd but familiar pattern: The men gathered outside to talk, and the women stayed inside.

“The houses were bugged,” Bradbury Reid said. “It didn’t seem weird at the time, but you look back on your life and realize what was unusual about these parties.”

With World War II behind it and the dawn of the Cold War emerging, the U.S. national security apparatus that created Hanford and Los Alamos was awash with paranoia.

“Dirty fingers reaching everywhere”

In the early 1950s, gay men employed by the federal government were being arrested at known “cruising” sites in Washington, D.C., Russia had emerged as America’s rival in the nuclear arms race and Dwight D. Eisenhower was elected to the White House on a Republican platform promising to remove “subversives” who’d ostensibly infiltrated the federal government.

Together, these factors spurred Eisenhower to issue an executive order in April 1953 that adopted harsher policies targeting gay employees, with the FBI as enforcer.

The fact that Hoover himself was secretly gay, and had a deep fear of being outed, was “massive irony piled on top of massive irony,” said John Ibson, professor emeritus of American studies at California State University, Fullerton, who has studied gay life inside the Manhattan Project.

“The more we learn about the FBI the worse it gets,” Bradbury Reid said. “It was generating more blackmail than information. The FBI’s dirty fingers were reaching everywhere.”

The same year Eisenhower ordered a crackdown on gay federal employees, Hoover’s FBI was bearing down on Oppenheimer and his inner circle for suspected support of the Communist Party. He was stripped of his Q clearance in 1954, as chronicled in the movie. It was posthumously reinstated in 2022, with a statement from Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm that read, “As time has passed, more evidence has come to light of the bias and unfairness of the process that Dr. Oppenheimer was subjected to.”

While homosexuality had not until Eisenhower’s order been regarded as a disqualifying factor for Q clearances, Hoover’s agents had been aggressively sopping up evidence for years. With the new federal order, which excluded gay people from federal service, that information became weaponized.

Eisenhower’s order appears to have ended the careers of at least some of the Manhattan Eight.

As of June 1953, Annie’s clearance was withheld, and she was terminated from Hanford.

Betty held a Q clearance in early 1953 but soon left and wouldn’t be considered for reinstatement based on the FBI’s findings.

Helen, a nurse at Los Alamos Medical Center who lived with another woman who was equally “sour on men” after unhappy marriages, according to an informant, had voluntarily left her job.

Claire faced “a serious question of eligibility for continued security clearance” and was ordered to undergo another investigation if she wished to stay at Hanford. There’s no record that she did.

After that, the public record trail of the Manhattan Eight runs cold. The Times couldn’t find other mentions of them in available documents, and the Department of Energy said it was unable to say what happened to them next.

However, their personnel files may be in a trove of records donated to the Washington State Historical Society under an agreement that keeps them sealed until 2030.

Arrest records from the cruising sites in Washington, D.C., provide a far more robust historic picture into the life of gay men of that era than lesbians, according to Biro Walters.

Aside from the Atomic Energy Commission memos, little remains known about the experiences of lesbians inside the early nuclear weapons program.

“It’s deeply unsettling and really should be a cautionary tale,” said Franklin of the Hanford History Project. “They wouldn’t have been a risk if we had been able to accept people for who they are.”

©2023 The Seattle Times.

Visit seattletimes.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.