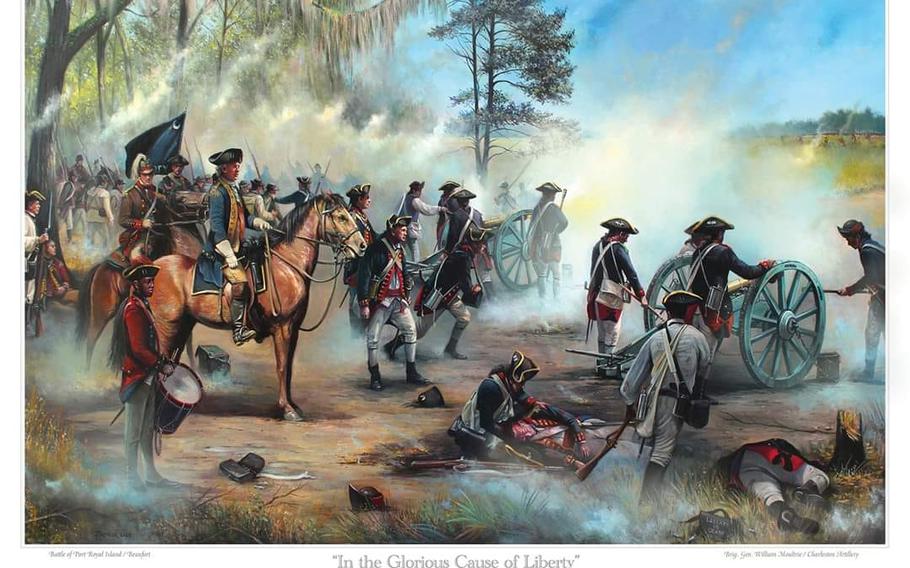

On Feb. 3, 1779, musket shots and cannon blasts rang out across 20 acres of high ground in a wooded area six miles north of downtown Beaufort, S.C. When it was over, the Patriots remained in control of Port Royal Island. (Facebook)

(Tribune News Service) — It was an unlikely mix of soldiers: Some were Black slaves. Others were "Hebrew" merchants. Two were Founding Fathers. But they were all patriots with a common enemy, the British, who were looking to snatch Port Royal Island from the control of the Continental Army and use Port Royal Sound as a deep-water port in the southern theater of the Revolutionary War.

On Feb. 3, 1779, musket shots and cannon blasts rang out across 20 acres of high ground in a wooded area six miles north of downtown Beaufort, S.C. When it was over, the Patriots remained in control of Port Royal Island. Eight Continental Army soldiers were dead and 22 wounded. Casualties on the British side were estimated at 40, and 10 were captured.

The battle wasn't big. But it was notable. For one, the Continental Army won, although the British later conquered Charleston and got their southern port, says Doug Bostick, CEO of South Carolina Battleground Trust, a not-for-profit land trust.

But more than that, Bostick says, the Battle of Port Royal Island broke ground when it came to race and religion and service in the military.

It is one of the earliest documented uses of Black troops in the Revolutionary War. And what may have been the only documented company of Jewish militia joined them in the fight.

Joining the unusual collection of Patriots were two signers of the Declaration of Independence. Never before had two signers picked up guns and fought in the same battle.

Yet as it stands now, other than a tiny battlefield marker that provides a few details, no features identify the battlefield off of U.S. Highway 21 near the Highway 21 Drive-In as a Revolutionary War site. One day earlier this week, cars whizzed past doing 60 mph. Much of the area has been developed with homes and commercial buildings and Marine Corps Air Station Beaufort — where part of the battlefield lies — is located across the highway, behind a barbed-wire fence.

"Even within Beaufort, it's probably little known," Bostick says of the Battle of Port Royal Island.

That's why efforts are underway today to protect the site and its historic value, artifacts and raise its profile with the public.

In 2020, government, land conservation and history groups teamed up and bought two parcels for $1.8 million from John Harris, owner of the Harris Pillow Co., and Mike Kling.

Bostick's group, which works to save battlefields, holds the conservation easement that protects it. Beaufort County owns the deed.

In the meantime, as the nation prepares to celebrate its independence July 4, here's five facts about the groundbreaking battle in Beaufort.

1. Port Royal Sound was in jeopardy

The Battle of Port Royal Island occurred on Feb. 3, 1779, on what would one day become the Harris Pillow Co. and the Marine Corps Air Station Beaufort, about the half-way mark in the seven-year war from April 19, 1775, to Sept. 3, 1783.

The British, who already controlled Savannah, were looking for another deep-water port in the war's southern theater where they could stage supplies and troops and set their sights on Port Royal Sound.

In late January 1779, 200 British regulars, led by Maj. William Gardner, were sent to seize Port Royal Island arriving via the Broad River at present day Laurel Bay and they continued toward Beaufort, destroying plantations along the way.

More than 250 American troops, most of them Beaufort militia and led by Brig. Gen. William Moultrie of Berkeley County, S.C., met the British on the highest ground of the island, a rise called Grays Hill.

The British positioned themselves at the edge of some woods, advancing with bayonets fixed. The Americans lined up in an open field outside musket range.

The Americans fired first with artillery, and then followed the initial barrage with musket volleys.

It was over in 45 minutes when the British retreated, with Patriot Moultrie observing that the action was "reversed from the usual way of fighting between British and Americans; they taking the bushes and we taking the open ground."

2. Declaration signers lay down pens and pick up guns

It was the only battle in the American Revolution where two signers of the Declaration of Independence fought in the same battle. Thomas Hayward Jr. was from the Beaufort District. The ruins of his home are in Jasper County. Edward Rutledge was from Charleston. Both were patriots and captains in the Charleston artillery battalion.

"That's a pretty rare thing," Bostick said. "A lot of the men that were signers were older men. This is the only battle where you have two signers that actually fought in the battle."

3. King Street Jewish merchants join the fight

One of the militia units with the Patriots was a Jewish militia company from Charleston. When militia companies were formed, they were usually mustered in bases where they lived, Bostick says. The Charleston Regiment of Militia was mustered in on King Street and included Jewish merchants who operated retail stores and lived above their businesses.

A 1910 article written about the group noted there were "26 Hebrews in this Volunteer Company raised on King Street." They were called "The Company of Free Citizens."

While a number of Jewish patriots fought in the war, this may be the only documented company of a Jewish militia, Bostick says.

"There's just not that much written about it but there are a number of significant Jewish patriots," Bostick said. "And there are a number of Jewish men who helped finance war. This is the only militia company that's primarily Jewish.

4. Jim Capers, a Black soldier, became a war hero

The battle is one of the earliest documented use of Black troops in the Revolutionary War who fought for the country's independence even though they themselves were slaves.

One was Jim Capers, drum major in the 4th Regiment of the South Carolina Militia, who later became a war hero. During the Revolutionary War, Bostick notes, a regimental drummer used the drum to transmit orders. Carrying no weapon, they were at particular risk. Capers survived the Battle of Eutaw Springs with sword and musket ball wounds on his face and head.

Capers, who was born Sept. 23, 1742, in Christ Church Parish, S.C. (Mt. Pleasant), enlisted when he was 13. Besides the Battle of Port Royal Island and Eutaw Springs, he also fought in the Siege of Savannah, the Siege of Charles Town, and the battles of St. Helena, Georgetown, Camden and Biggin Church. He was even present for the surrender of Cornwallis, the commanding British general.

Capers fought the entire war and was granted freedom at the end of his service, "which is a pretty incredible thing," Bostick says. Capers died in Pike County, Ala., on April 1, 1853, at the age of 110.

"The American Army was never again as integrated until you get to World War II," Bostick said. "There were enslaved Blacks and free Blacks both fighting in the American Revolution."

Some Black soldiers also fought for the British, who offered freedom to any slave willing to fight with them, Bostick said.

5. How to see the site

There's not much to look at now and the battlefield is easy to miss traveling along busy Highway 21.

It's located on the west side of the highway, just north of Parker Drive. A small sign explains the battle, but no work has been done on the battlefield itself, which is overgrown with trees and brush.

The rest of the site is inaccessible to the public as its located on Marine Corps Air Station Beaufort.

But efforts are underway to improve the site and make it easier to visit. Now that the property is in public hands, the South Carolina Battlefield Trust plans to work with Beaufort County on producing markers that show the American and British lines and narrative panels explaining the significance of the battle and how it unfolded. That's expected to happen in 2024.

John Allison, an independent metal dictation archaeologist from Columbia, has thoroughly surveyed entire battlefield.

"By 2016 we pretty well knew the battlefield footprint and had a good understanding of where it was located," Bostick said.

(c)2023 The Island Packet (Hilton Head, S.C.)

Visit www.islandpacket.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.