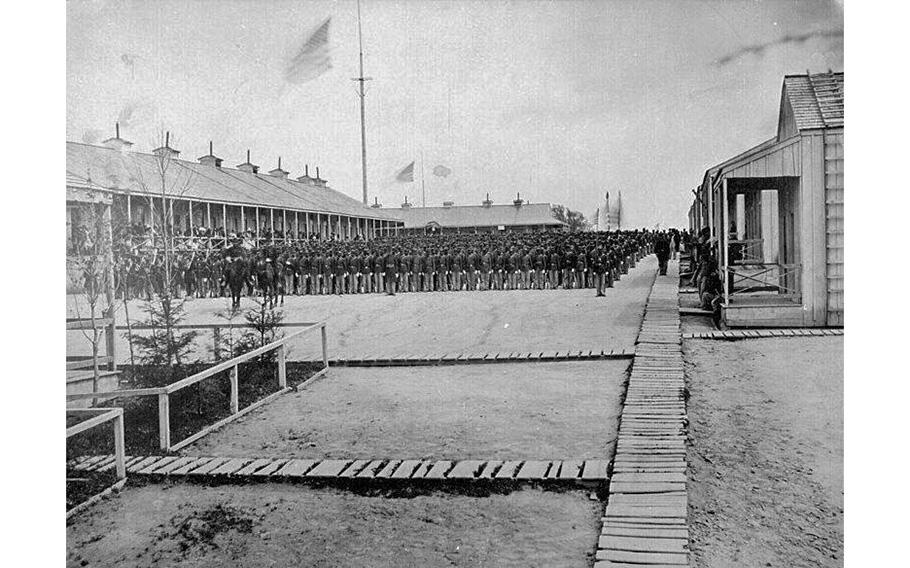

African Americans were among the first to volunteer to fight for the Union Army during the Civil War. (Facebook/135th U.S. Colored Troop)

(Tribune News Service) — African Americans — among the first to volunteer to fight for the Union Army during the Civil War — have been among the last to get recognition for their service.

But the men of the 135th U.S. Colored Infantry Regiment got their due this week with the unveiling of a Civil War Trails marker in downtown Goldsboro.

As state and local dignitaries, Civil War reenactors and descendants of some of the actual soldiers of the 135th lifted the drape off the new marker, a woman in the crowd shouted, “About damn time.”

One hundred and fifty-eight years, to be exact.

It was another Monday, March 27, 1865, that the 135th was formed in Goldsboro from a group of men who had served for months in the Pioneer Corps for the army of Gen. William T. Sherman. Pioneers did the work that engineer brigades and reservists do now: building roads, bridges and fortifications, the infrastructure that makes it possible for troops to move forward and fight.

Sherman’s army of some 60,000 soldiers had arrived in Goldsboro on March 21, having completed the general’s scorched-earth march from Atlanta to Savannah, Ga., north to Columbia, S.C., and on to Fayetteville, Averasboro and Bentonville. In Goldsboro, he met up with forces from Ohio, increasing his number nearly 89,000 troops.

Shedding light on a story few know

Early in the war, Blacks had not been allowed into the Union army, whose leaders had racial prejudices and fears that Black enlistment would cause political dissent to spread into border states outside the South. But in 1862, Congress changed the rules and President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, both clearing the way for the recruitment of another source of military might.

The Bureau of Colored Troops was formed in 1863. Eventually more than 200,000 Black men would serve in the U.S. Army and Navy during the war, according to the American Battlefield Trust, which says they fought in 450 engagements, including at Fort Fisher and Wilmington, and lost more than 38,000 men.

Few people knew the story of the 1,100 men of the 135th formed at Goldsboro until eight years ago, when a local couple, Jay and Amy Bauer, heard mention of the regiment during a program at the Wayne County Museum and began a quest to learn more.

At Monday’s event, the couple said they had made at least eight trips to Washington, spending hours in the National Archives going through pension records and other documents that allowed them and a team of volunteer researchers to locate the graves of many of the soldiers and find more than 100 descendants.

Elizabeth Martin Meggett of Boone represented those family members Monday.

Her great-grandfather, originally named Harry Martin, was born into slavery on a farm in Sampson County around 1846 and was later given to the farmer’s daughter as a wedding gift.

He escaped and made his way to Goldsboro in time to join the 135th USCT as it was being organized and put under the command of Col. John E. Gurley.

Like the other soldiers, Meggett said, he was given the blue uniform of the U.S. Army, complete with the jacket with the brass buttons with the eagle stamped in relief.

The Grand Review in Washington

From there, researchers say, the 135th marched with Sherman’s troops to Raleigh, then to Petersburg, Richmond, Fredericksburg and Alexandria, Va.

On May 24, 1865, their pension records proudly say, the 135th took part in the Grand Review in Washington, a two-day celebration of the Union victory that brought 145,000 troops down the streets of the wounded nation’s capital.

After the war, Meggett said, her great-grandfather returned to Wayne County where he married, started a family and began buying the farm land that her family still owns and works today. In 1885, she said, he applied for an Army pension but was denied because he couldn’t prove his identity or his military service; having been a slave, his last name had been changed and then misspelled, a mistake he didn’t correct because he couldn’t read.

It had been illegal to teach slaves to read.

When he did get his pension, the government shorted him, Meggett said, and he kept fighting until he was paid what he was owed. It took 20 years to get it straightened out, she said.

Even with all they went through, Meggett and other family members say, by just two or three generations later, most people didn’t believe there had ever been a USCT regiment organized and mustered in at Goldsboro. Some are surprised there were Black soldiers in the Civil War at all.

“People just didn’t believe it,” Meggett said, but the research into the 135th proved it was true.

Civil War Trails system

The marker honoring the regiment is part of the six-state Civil War Trails system that guides visitors to more than 1,200 sites, each brought into the program by the grassroots efforts of the communities where the events took place.

Those who worked to get the mustering of the 135th USCT included in the Civil War Trails system hope it will bring heritage tourists to Goldsboro, about 50 miles southeast of Raleigh, also the site of Willowdale Cemetery where some 800 fallen Confederate and Union soldiers are buried in a mass grave.

For Meggett, the marker on Center Street near the intersection with Chestnut is a kind of coda, a long-awaited final note to the very American story of the soldiers of the 135th, including her great-grandfather, who was listed as Harry Rawl on the regiment’s roster.

“It’s time they get their recognition,” she said. “We’ve never acknowledged what they did.”

©2023 The Charlotte Observer.

Visit charlotteobserver.com.

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.