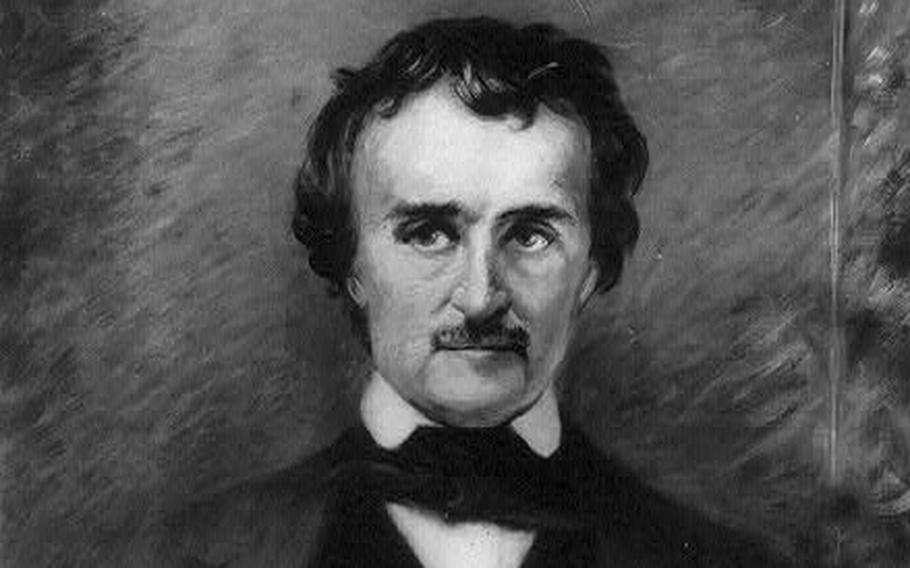

A painting of Edgar Allan Poe circa 1921. The artist is listed by the Library of Congress as Mrs. Norman Burwell. (Mrs. Norman Burwell/Library of Congress)

He’s our reigning master of the macabre, whose ghostly imagination still transports us to the eeriest of places. But one of Edgar Allan Poe’s darkest stories didn’t come from his pen. It’s the haunting mystery of his own death.

On a fall morning in 1849, Poe died in a Baltimore hospital after a stranger had found him “in great distress” a few days earlier outside a polling place during an election. The 40-year-old had been missing for almost a week. His deathbed symptoms — fever and delusions — were so vague that they’ve spawned dozens of theories, including poisoning, alcoholism, rabies, syphilis, suicide and homicide.

Now an Ohio journalist has conducted an extensive investigation into Poe’s death. In his new book, “A Mystery of Mysteries: The Death and Life of Edgar Allan Poe,” Mark Dawidziak contends that the evidence points to tuberculosis, an illness that is forever linked to artistic genius and literary martyrdom. But he says there’s a co-conspirator: an affliction known as election fraud.

Dawidziak believes that Poe failed to get proper medical care because he was “cooped” — an election-rigging scheme at the time that involved snatching someone from the streets, confining and perhaps drugging him, then trotting him out to vote again and again.

“It’s a very Baltimore explanation,” Dawidziak said. “It was a tough, tough town, nicknamed Mobtown because they took their rioting seriously.” Poe knew this as well as anyone: In 1835, when he and his family lived in the city, a three-day riot over the failure of a local bank left prominent houses burned and at least 12 people fatally shot.

While Poe will forever be linked to Baltimore — his final resting place and the home of an NFL team named in honor of his poem “The Raven” — he was only passing through the nation’s second-largest city right before he died. (Baltimore, in an overwhelmingly rural country, towered over Philadelphia, Boston and New Orleans in 1850 with a population of 169,000.)

On Sept. 27, 1849, Poe appears to have boarded a steamer in Richmond, where he had been wooing a childhood sweetheart. A day later, he disembarked in Baltimore, apparently to catch a train to Philadelphia, where he had a temporary poetry-editing gig lined up, before going on to New York City, the only U.S. city with more people than Baltimore.

Poe didn’t make a habit of disappearing. He was lively and fun-loving, not the “dark and brooding” author of legend, nor a “drug-crazed madman wandering out at night howling at the moon,” said Poe scholar Hal L. Poe, a theologian at Tennessee’s Union University whose great-great-grandfather was Poe’s cousin. But vanish he did.

It later emerged that no one had seen him for several days after he left Richmond. Then, on Oct. 3, 1849, a Baltimore passerby discovered a semiconscious Poe and alerted one of the writer’s friends that he was in bad shape in front of Gunner’s Hall tavern. Contrary to legend, Poe was not found in the gutter, and he didn’t die on a bench or in the street, said Enrica Jang, executive director of Baltimore’s Edgar Allan Poe House & Museum.

Poe was disheveled and wearing shabby, ill-fitting clothes that weren’t his, according to Hal Poe. “He always took great care in his appearance,” Hal Poe said. “He was fastidious in his dress. Even if his cuffs were threadbare, and his socks were darned, they were all very nice.”

Poe’s clothes seem to be an important clue. He turned up on election day, and the tavern where he was found served as a polling place as Marylanders chose their representatives in Congress. (At the time, states set their own election dates.) This is the crux of the theory that Poe was “cooped.”

Around election time, “ruffians would go out in the street, find someone vulnerable and indigent, hit them over the head, ‘coop’ them up in a room, and feed them alcohol and maybe opium until it’s time to vote,” Jang said. The kidnappers might change the man’s appearance throughout the day, she said, so they could fool election workers and have the person vote multiple times.

Maryland didn’t have a voter registration system at the time. Many men were allowed to vote if a poll official or local resident recognized them, said Jon Grinspan, a political history curator at the Smithsonian Institution. All they had to do was submit preprinted party-line ballots — published in newspapers and distributed by partisans — that listed the candidates they supported. (Secret ballots that allowed voters to choose individual candidates didn’t become common until after the Civil War.)

“There was a fair amount of illegal voting, often at tumultuous polling places in environments like big cities or on the frontier,” Grinspan said.

Just about every Poe scholar believes he was “cooped,” Hal Poe said. He may have been especially vulnerable to kidnapping because he was drunk or ill — or both — when he left the steamer.

Dawidziak doubts Poe had been drinking. It’s true that he had long struggled with liquor, Dawidziak said, making alcoholism a “major accomplice” in Poe’s death by taking a toll on his health. But Poe had taken a temperance pledge shortly before he disappeared.

It’s more likely, Dawidziak believes, that Poe was sick and got worse while he was missing.

“This was cold, damp early October in Baltimore. If something was physically wrong with Poe, being cooped — kept in chilly and spartan conditions — could have been disastrous for his system,” Dawidziak said. “Add any amount of alcohol to the mix, and the effects would have been devastating.”

While election fraud may have contributed to Poe’s demise on Oct. 7, 1849, at Washington University Hospital, it’s not a cause of death. Dawidziak sought to understand more by interviewing about four dozen Poe scholars, physicians and other experts. He can’t say for sure what happened, but he believes several prevailing theories are unlikely.

A 1998 book suggested Poe was beaten by three brothers of the woman he hoped to marry, but there are no reports that Poe had bodily injuries. Another theory proposes that Poe was poisoned by the coal gas that generated light in homes, but 21st-century forensic tests of locks of hair retained after his death showed no signs of poisoning by the heavy metals that coal emits when burned. Yet another suspect is rabies — Poe loved cats, Hal Poe said — but he didn’t show the common symptom of an inability to swallow water.

As for suicide, it seems unlikely, since Poe’s life was going well. He’d spent the summer in Richmond, “the city of his heart,” Dawidziak said. It looked as if new funding would help him finally achieve his dream of publishing a literary magazine. And he was in love with a woman he hoped to marry.

Dawidziak kept coming back to one possible solution to the mystery: tuberculosis, the disease that’s blamed for taking the life of his wife, Virginia — the cousin he’d famously married when she was 13 — as well as those of his parents and his foster mother.

“Almost every medical expert and pathologist that I have talked to said there is absolutely no question Poe had tuberculosis,” Dawidziak said. Specifically, he believes that Poe died of tuberculosis meningitis, which causes the membranes around the brain to swell. As his book explains, Poe probably had dormant tuberculosis for years, making it more likely that it would travel outside the lungs. He had appeared to be sick for some time before his death, and his symptoms, including fever and delusions, also would fit.

Even if he didn’t have contact with infected relatives, it would have been hard for Poe to avoid infection. “There was an explosion of tuberculosis in the U.S. at this time,” and the majority of urban residents may have been infected, said health journalist Vidya Krishnan, author of 2022’s “The Phantom Plague: How Tuberculosis Shaped History.” The disease, like COVID-19, is spread through coughing and sneezing. And it didn’t help that the United States was a nation of spitters, as a disgusted Charles Dickens described it.

As for the meningitis, it’s not unusual for tuberculosis to spread throughout the body once someone is infected, Krishnan said. “It’s exactly like cancer,” she said. “I’ve met patients with TB in the eye, in their spine, in their ankle bone, in the spleen, the lymph nodes.”

If Poe did die of tuberculosis, he has illustrious company. The disease, also known as consumption, is blamed for the deaths of many well-known writers and musicians, including poet John Keats, composer Frédéric Chopin and at least two of the Brontë sisters.

But the slow, lingering deaths from the illness were hardly as “romantic” as they were often portrayed in 19th-century culture, Krishnan said.

It may be possible to learn more about Poe’s death by exhuming his body from its resting place in a Baltimore graveyard and examining his skull for signs of markings caused by meningitis. (This wouldn’t be a first for Poe: He was dug up in 1875 when his remains were moved to another part of the cemetery under a new monument dedicated to him. Witnesses made sure to inspect the well-preserved bones of the famous writer before he was reburied.)

But Jang, of the Edgar Allan Poe House & Museum, hopes the man considered to be the inventor of the detective story stays right where he is.

“I don’t want to disturb the dead,” she said, “and his death being a mystery is very satisfying to me.”