Landon Grove, director and curator of the Fort Ritchie Museum, stands near an original mural. The art work was uncovered in a building at Fort Ritchie where Nisei, second-generation Japanese-Americans, worked during WWII. The now decommissioned US Army post was used from 1942-1946 as an Army Military Intelligence Training Center. In 1944, over 500 Nisei worked in counterintelligence at the base. (Kim Hairston/TNS)

(Tribune News Service) — A Japanese American soldier from California who was sent to Japanese concentration camps has been identified as the potential artist behind a mysterious mural at the former Fort Ritchie in Cascade, Washington County.

Nobuo Kitagaki — an established artist who died Sept. 22, 1984 — is believed to have painted the roughly 12-by-4-foot Nisei mural that depicts four people creating and painting ceramics inside Building 305.

The mural was thought to have been painted in 1944 or 1945 by a Nisei — a Japanese term that refers to children of Japanese immigrants or second-generation Japanese Americans — because the building was used by Nisei soldiers during World War II.

The artwork had been boarded over by plywood for an unknown number of years until Fort Ritchie’s latest owner discovered it last summer after deciding to turn the dilapidated structure into an artisan village.

News of the mural’s discovery was popular among Nisei groups, who contacted Landon Grove, the fort’s historian, to help find the artist.

Kimmy Tanaka, with the Minnesota Historical Society, linked Grove to the “Soldier Art” exhibit in the summer of 1945 at The National Gallery of Art, leading to a name.

How historians searched for the mural’s artist

In December 1944, the War Department, known today as the Department of Defense, announced a National Army Arts Contest to stimulate interest in art as an off-duty recreational activity during the war.

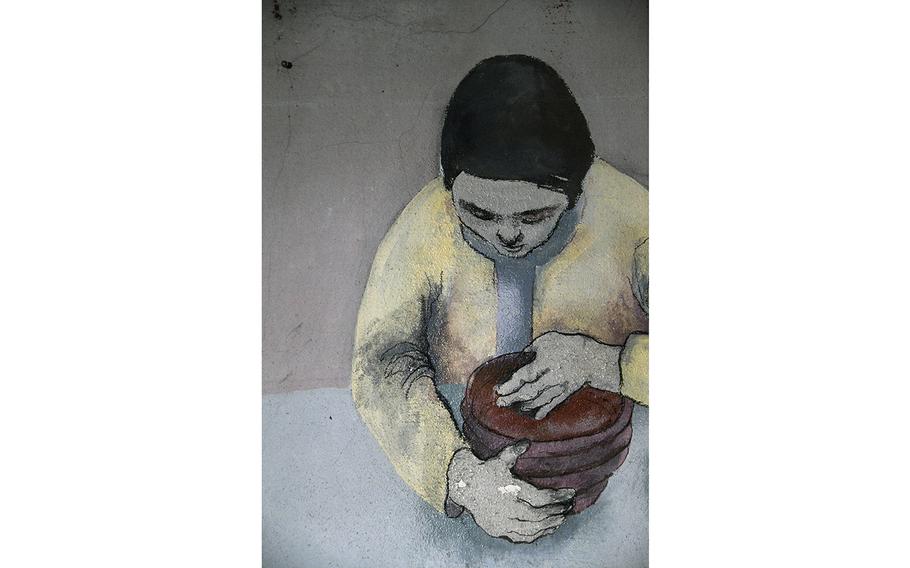

Detail of original mural uncovered in a building at Fort Ritchie where Nisei soldiers, second-generation Japanese-Americans, worked during WWII. The now decommissioned US Army post was used from 1942-1946 as an Army Military Intelligence Training Center. In 1944, over 500 Nisei worked in counterintelligence at the base. (Kim Hairston/TNS)

Participants submitted some 9,000 entries to their service command headquarters, and 1,500 pieces were displayed at regional exhibits throughout the country, including Baltimore, according to the National Gallery.

Winners received $100 war bonds, and winning pieces were later displayed at a special exhibit at the National Gallery in 1945. Some of these artworks were illustrated in a book, “Soldier Art,” that Grove bought.

“On Page 130, was an illustration, which to me showcases the same kind of artistic style and composition as the Ritchie mural,” Grove said, who first discovered the mural’s existence.

The illustration, “Design for Ballet — Indian,” was painted in 1944 in gouache and ink by Pfc. Kitagaki at Fort Snelling in Minnesota.

It shows five people in outfits, some wearing masks, and appears to explore different costume ideas for a Native-American-themed ballet, Grove said.

“The tell in all of the works that I saw of Kitagaki is that when he outlines his characters, he uses a very prominent black line, but the black line does not cling to his subjects,” he said, noting he repeatedly saw this in Kitagaki’s works.

Photographs of the painting provided by Kitagaki’s nephew, Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer Paul Kitagaki Jr., indicate that it was in an Army arts show in 1944 in Washington, D.C.

“The facial structure of two of the people depicted, paired with the broadly thick black ink, which outlines his character is emblematic,” Grove said. “I feel very convinced that Kitagaki was the muralist behind the image at Ritchie.”

Who was Nobuo Kitagaki?

Kitagaki was born Feb. 10, 1918, in Oakland, California, to parents from Kumamoto prefecture in Japan, according to Densho, a nonprofit that preserves Japanese American history, specifically the incarceration of Japanese Americans during WWII.

He was one of five children who grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area. After WWII began in 1939, the following year Kitagaki registered for the U.S. Army at age 21, according to his registration card.

Kitagaki and his family were forced to move when Executive Order 9066 authorized the mass removal of almost 120,000 Japanese Americans, including native-born Americans, to concentration camps in 1942.

They relocated to Tanforan Assembly Center in San Bruno, California, and then to a camp in Topaz, Utah, where Kitagaki volunteered for military service and left the camp in June 1943, Paul Kitagaki Jr. said.

“He and my parents never spoke about their time there,” said Paul Kitagaki Jr., adding that he sometimes learned about his family’s history on his own. “It was a very hard time. They lost a lot.”

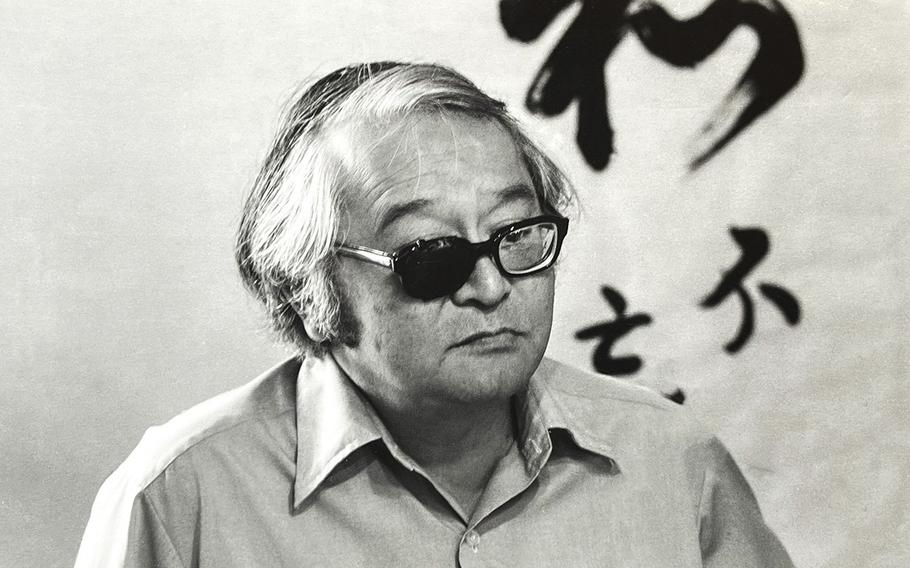

San Francisco artist Nobuo Kitagaki as seen in April 1978. On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which forcefully relocated many Japanese Americans. Kitagaki was incarcerated in the Tanforan Detention Center and later the Topaz Incarceration Camp in Utah. He later volunteered for the U.S. Army during WWII. (Courtesy of Paul Kitagaki Jr./TNS)

According to the Department of Veterans Affairs, Kitagaki enlisted in the Army on May 8, 1944. He served in the Military Intelligence Service and later in the Special Services when the Army took note of his artistic abilities.

Coincidentally, Kitagaki was stationed at Fort Ritchie the same time that the regional Soldier Art exhibit was happening in Baltimore.

Fort Ritchie mural

Kitagaki trained at Fort Ritchie from May 2 to June 15, 1945, according to historian Beverley Driver Eddy — a scholar at Dickinson College in Pennsylvania and author of “Ritchie Boy Secrets: How a Force of Immigrants and Refugees Helped Win World War II.”

“That was news to me that he was stationed in Maryland,” Paul Kitagaki Jr. said. “I always thought he was stationed in Minnesota.”

Kitagaki was a member of the 3rd Mobile Intelligence Training Unit, whose 26 members trained at Fort Ritchie before being sent on a demonstration tour of camps preparing men for service in Japan, Eddy said.

Building 305 was used by Nisei soldiers for intelligence training, and Kitagaki would have been there and possibly painted the mural, Grove said.

During that time, about 200 art pieces, selected from 540 entries from Army camps in Maryland, Pennsylvania and Virginia, were also on display at the Baltimore Museum of Art in May 1945, according to The Baltimore Sun archive.

Camp Ritchie training records dated June 30, 1945, listed Kitagaki as a private first class when he left the camp. Kitagaki was discharged May 6, 1946, as a sergeant.

He then went to several art schools, including in New York, Chicago and California, where he ultimately built his post-war art career in San Francisco, according to Densho.

Paul Kitagaki Jr. recalled his “Uncle Nob” supporting him as he was beginning his photography career.

“How he influenced me was he gave me a book called ‘Goodbye Picasso,’ and he also told me that our family had been photographed by Dorothea Lange,” Paul Kitagaki Jr. said.

Lange is one of his photographic heroes, Paul Kitagaki Jr. said, and after researching and finding photos of his family that Lange took during WWII he was inspired.

Paul Kitagaki Jr. is not sure if his uncle actually painted the Nisei mural at Fort Ritchie, but it’s interesting to know he was stationed there and that perhaps a piece of his work exists in Maryland.

©2023 Baltimore Sun.

Visit baltimoresun.com.

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.