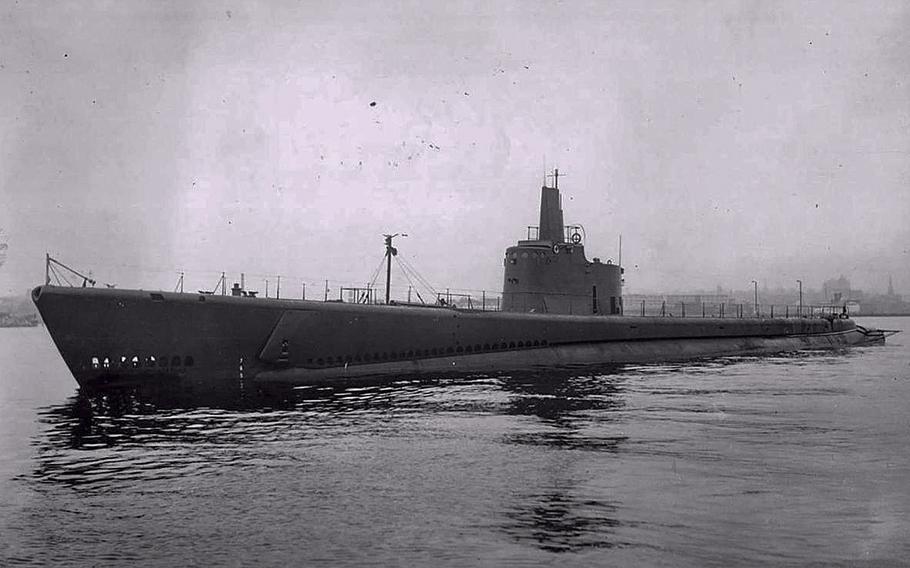

USS Albacore shortly after its launch in 1942. (U.S. Navy)

(Tribune News Service) — One had been a star high school athlete who enlisted in the Navy. The other was a recent Tulane graduate in mechanical engineering.

Both were New Orleans natives who found themselves aboard the same doomed submarine along with 83 other sailors in the Pacific during World War II, the exact location of their final resting place unclear.

Until now. Nearly 80 years later, a retired Japanese scientist using an unmanned underwater vehicle has located the remains of the USS Albacore — the submarine that Nicholas John Cado and John Francis Fortier Jr. were aboard when it was sunk by a mine.

“I will always remember the day they got the telegram,” said Cado’s cousin Bonnie McGuinness. “It was just such a sad day because he was a young man, a sad day for everyone.”

The U.S. Navy confirmed the discovery in February and notified the sailors’ survivors, bringing to a close a mystery that began on Nov. 7, 1944. That was when the Albacore was off the coast of Japan, looking for shipping targets.

Both New Orleans sailors were on their first cruise aboard the submarine when it went down in nearly 800 feet of water a few miles east of the Cape Esan lighthouse on the southeastern peninsula of Hokkaido.

‘A very handsome man’

Seaman First Class Nicholas John Cado was only 20 when the submarine was sunk. He had graduated in May 1943 from L.H. Marrero High School, where he was a football and basketball star.

“My memory is that he enlisted in the Navy right after he graduated from high school,” said McGuinness, who was born on Dec. 8, 1941, the day after Pearl Harbor.

At Marrero High, Cado gained honors as a fullback on its football team, scoring at least six touchdowns in the 1942 season. And his skills on the school’s basketball team later that year saw him named honorable mention in The Item’s list of basketball all-stars among the Riverside Prep League.

McGuinness said most of her memories of Cado were from stories told by her mother, who was Cado’s sister, and other relatives.

“His first assignment was at a women’s military base as a lifeguard,” she said. “And he was a very handsome man. He had dark curly hair with a moustache.”

At Christmas in 1943, Nicholas was able to spend time with his two brothers in Hawaii, Marine Corps Gunnery Sgt. Joseph A. Cado, who was recovering from wounds received on Tarawa and was being treated at a hospital in Honolulu, and Navy Radioman Third Class Anthony D. Cado, who was serving on a subchaser.

“He sent me a little Hawaiian skirt and top and lei, and I was told it was from him,” McGuinness remembered.

Records indicate Cado was transferred to the Albacore on Oct. 24, 1944, just two weeks before it was lost. The submarine was declared missing on Dec. 12, and the crew was declared dead a year later, on Dec. 13, 1945. Cado’s rank was elevated to seaman first class and he was awarded a Purple Heart.

‘Quite a jokester’

John Francis Fortier Jr., who went by the nickname Buddy, had graduated from Tulane University in May 1943 with a degree in mechanical engineering and immediately went to Annapolis for training, being commissioned in August as an ensign.

He graduated from submarine school at New London, Conn., in April 1944 and ended up on the Albacore for his first assignment in October of that year as an assistant engineering and commissary officer.

Fortier was related to two major figures in New Orleans area history. His grandfather was Alcee Fortier, the historian and romance languages professor who ended his career as dean of Tulane’s graduate school. Alcee Fortier High School, which operated in Uptown New Orleans between 1931 and 2006, was named after him.

Fortier’s uncle was Judge Leander Perez, the political kingpin for a half-century in Plaquemines and St. Bernard parishes.

“We called him Uncle Buddy and we were told that he died on his first trip out on a submarine, that it was a land mine,” said niece Helen Cloyd Elias.

“I know he was apparently quite a jokester,” she said. “He and his buddies would come and aggravate my mother, who was his older sister.”

Elias said she believes Fortier enlisted in part because he thought he’d have to support the rest of his family.

Fortier, who was 22 when the Albacore sank, had his rank elevated to first lieutenant and was awarded a purple heart when declared dead. He was among 134 one-time Tulane students who were killed during World War II.

His name was read during a June 20, 1946, memorial convocation at the university whose guest of honor was then Fleet Adm. Chester W. Nimitz, who was commander in chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet when the Albacore was lost. Nimitz was chief of naval operations at the time of the convocation.

“If civilization is not only to endure but to progress, if our America is to realize the richness with which God endowed it, then we must all dedicate our lives in living, as these your brothers did in dying, so that liberty, peace, and progress shall embrace all mankind,” he said during the convocation.

‘Gave their life’

Navy records show that the Albacore was among the most successful U.S. submarines during the war, conducting 11 patrols and credited with 10 confirmed and three possible enemy vessel sinkings. Six of the 10 confirmed sinkings were combat ships.

Its most important attack was the June 19, 1943 torpedoing of the 31,000-ton carrier Taiho, the Japanese navy’s then newest and largest floating aircraft carrier, during the Battle of the Philippine Sea. The carrier was the flagship for the Imperial Japanese Navy’s fleet of 60 ships and 24 submarines in its attempt to stave off the invasion of the Marianas Islands by the U.S.

On its last mission, the Albacore left Pearl Harbor on Oct. 24, 1944 with instructions to lay off the coast of Japan to look for shipping targets, but with a warning that mines were likely sown in the Tsugaru Strait between Honshu — the main island of Japan — and Hokkaido to its north.

According to Japanese records, a submarine assumed to be the Albacore struck a mine off the Hokkaido coast, near the strait, on Nov. 7.

“A Japanese patrol boat witnessed the explosion of a submerged submarine and saw a great deal of heavy oil, cork, bedding, and food supplies rise to the surface,” a Navy summary said.

In 2020, Tamaki Ura, a retired engineering professor from the University of Tokyo, decided to find the Albacore’s final resting place.

Ura was instrumental in the development of underwater remotely operated vehicles, and in 2017 had overseen an underwater mapping of 24 submarines off the coast of the Goto Islands of Japan, including one that side-scan sonar showed was sticking bow-up from the ocean bottom.

He also has studied the movement of radioactive cesium particles from the 2011 Fukushima nuclear plant meltdown in sediment off the Japanese coastline.

Using crowdfunding to raise about 2 million yen — around $15,000 — to help underwrite his search for the Albacore, Ura conducted a surface-based survey of the area in March 2022, delayed for a year because of the Covid-19 epidemic. The survey better identified the sub’s location.

During a second trip to the site that ended on Oct. 2, 2022, Ura’s ROV provided the evidence needed to convince U.S. Navy officials that the wreck was the Albacore.

The evidence included photos in murky water of key pieces of the sub’s architecture that had been modified before its final patrol, including the presence of an “SJ Radar” dish and mast, a row of vent holes along the top of the ship’s superstructure and the absence of steel plates along the upper edge of the ship’s fairwater, the easily recognizable superstructure holding its conning tower.

On. Feb. 16, the Naval History and Heritage Command announced that its Underwater Archaeology Branch used that information to confirm the wreck site was that of the USS Albacore.

“As the final resting place for sailors who gave their life in defense of our nation, we sincerely thank and congratulate Dr. Ura and his team for their efforts in locating the wreck of Albacore,” said NHHC Director Samuel J. Cox, U.S. Navy rear admiral (retired). “It is through their hard work and continued collaboration that we could confirm Albacore’s identity after being lost at sea for over 70 years.”

The wreck site is protected by U.S. law. Non-intrusive activities, such as remote sensing documentation, is allowed, but intrusive activities must be approved by the NHHC.

“Most importantly, the wreck represents the final resting place of sailors that gave their life in defense of the nation and should be respected by all parties as a war grave,” the command said in a news release announcing the discovery confirmation.

(c)2023 The Advocate, Baton Rouge, La.

Visit The Advocate, Baton Rouge, La. at www.theadvocate.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.