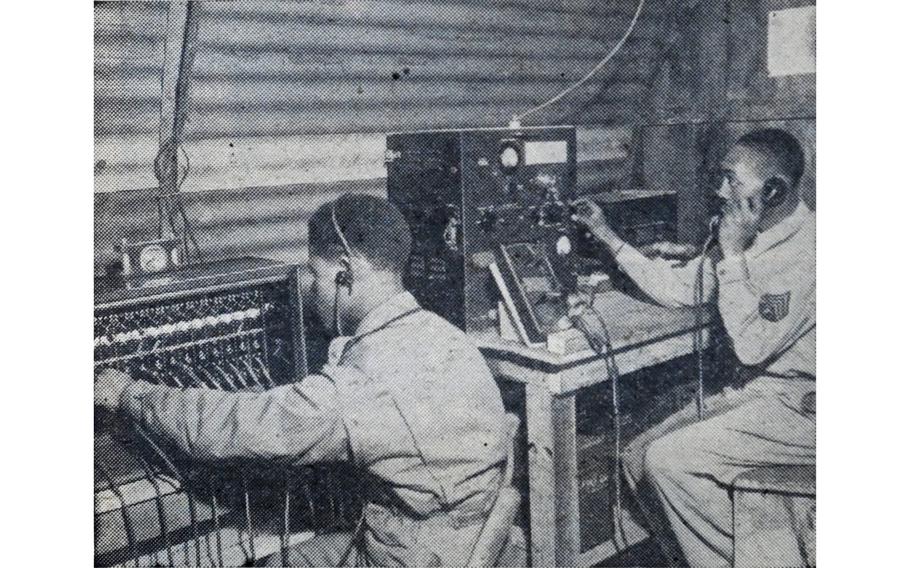

“Switchboard and radio operators work long shifts in the battery operations room, receiving information on aircraft movements in the vicinity of their battery,” read the original caption on this image, first published in the Northern Ireland edition of Stars and Stripes, Feb. 10, 1944. Two soldiers can be seen operating a switchboard and radio. (M.D. Weathers/Stars and Stripes)

This article first appeared in the Stars and Stripes Northern Ireland edition Feb. 10, 1944. It is republished unedited in its original form.

GUN crews of this Negro AA Battalion whose guns are emplaced on high, wind-swept hill-tops and the flat grain fields of farms in this section maintain a vigil by their 40mm. Bofors guns that never ceases, praying that Nazi planes will come their way.

This AA unit provides sole defense against aerial attack for some "of the most important U.S. supply centers and headquarters sites in the ETO. Each battery is deeply aware that upon it rests no small quota of responsibility for the protection of vast stores of vital Allied invasion equipment.

Each gun crew earnestly feels that should the Luftwaffe succeed in destroying anyone of the V.P.'s (Vulnerable Points) around which battery guns are situated the war might well be lengthened. These crack ack-ack men don't mean for that to happen, and their demonstrated accuracy of fire and enthusiasm at gun drill are indices of their determination.

In these days when new ways of war are constantly being devised AA outfits are likely to be ordered to apply their firepower to a wide variety of targets, on land as well as in the air, and so their training stresses versatility of firing techniques.

Before this battalion shipped from the States its name had become synonymous with the highest standards in AA circles.

Phenomenal record firing at towed aerial and anti-tank targets at training centers in Georgia and Illinois made for it its present excellent reputation, and before training had been completed it had received personal congratulations from General Leslie McNair, then Army Ground Forces Chief.

“Ack-ack men consider business good when they must pour clips of 40mm of ‘food’ into their guns,” read the original caption on this image, first published in the Northern Ireland edition of Stars and Stripes Feb. 10, 1944. The photograph shows three troops loading ammunition into a 40mm Bofors anti-aircraft gun, as another mans the controls. (M.D. Weathers/Stars and Stripes)

Confidence, therefore, was part of the equipment these youngsters brought with them when they came to the ETO and proceeded to assigned operational sites. These sites include some of the most important U.S. installations in the U.K.

Chafing now for lack of action against "live" targets hundreds of gun crewmen wait for Hitler's raiders with a grim intensity, clean and oil their guns with religious solemnity, and race through gun drills several times daily with a seriousness of purpose that conveys the impression that they are forcing themselves to believe that they are actually "tracking" German planes.

A battery of guns is directed from a centrally-placed Battery Headquarters containing an Operations Room which is the hub of the communications system. Battery Operations is in constant telephonic contact with the nearest GOR (Gun Operations Room) of the Air Defense of Great Britain and is kept informed of the movement of all aircraft aloft in the region. From the Battery's Operations Room radiate eight lines to each of the gun sites.

Instructions on firing transmitted to each of the guns from Battery Operations are based on data furnished by the British GOR and include location and number of all aircraft observed. This information is recorded on the Operations Plotting Board by "plotters," who follow in this way the course of friendly and hostile planes.

At each Battery Headquarters communications men are constantly on duty to receive signals and warning messages by telephone or radio, though radios are chiefly used for operations in the field.

Radio Operator Pfc. Isaac Gabriel is one of these communications men and he serves a 24-hour continuous period every three days.

Gabriel is small and intense of manner. He has the rare knack of being able to remain alert for messages from the GOR and to indulge in nostalgic thoughts of home in Miarna, Florida, which to him is a little house in Fourth Court on the outskirts of the constricted Negro district. Home, wife, kids and familiar haunts are far away, but somewhere in Gabriel's consciousness these things are deeply engraved. When the night is still and the only illumination in the Operations Room comes from the dial lights on the Signal Corps radio set, Pfc. Gabriel dreams of high school dances long ago, moonlit bathing on the Florida surf and a certain disastrous debut in the boxing ring — all without regrets.

“They spend many hours, even during their off time, improving their ability at aircraft recognition,” read the original caption on this image, first published in the Northern Ireland edition of Stars and Stripes, Feb. 10, 1944. Three soldiers, part of an African American anti-aircraft battalion, study models of airplanes flown by the German Nazi enemy. (M.D. Weathers/Stars and Stripes)

The individual gun positions are little settlements in themselves. There is a mess hall and kitchen from which the gun crew of 14 men is fed, Nissen hut or tent living quarters are latrines and wash sheds, all of which were constructed by the crews.

"These men are not engineers," said Capt. John Thomas, of Pennsylvania, a battery commander, "but in building these gun emplacements and huts with such ingenuity under the most unfavorable conditions they have done a wonderful job that any engineer unit would be quite proud of."

It is one of the duties of a battery headquarters to keep the gun sections regularly supplied with fuel and rations. It usually is the job of the first sergeant to see that this is done and 1/Sgt. William Harris Jr., of Chicago, Illinois, a typical battery top kick, executes his tasks with hard efficiency not unmixed with benign good humor.

Sgt. Harris, still wincing from the pain of a recently extracted wisdom tooth, is at his deck. The rain and the wind whir nastily against the sides of the headquarters hut and flashes of pain shoot through his head, but he continues to maintain contact with the guns. Calling all of the battery gun positions, he hooks them up in a net for issuance of daily orders. When he talks to the sergeants in charge of gun crews the softness goes out of his voice, and his tone is impersonal, harsh.

"All you gun sergeants will stand in readiness for practice drill in 20 minutes and get those men out faster than you did the last time … G-4, how is your coal supply? … G-7 is your power plant in working order yet? … G-1, send those two Catholic men in your crew over here in exactly one hour. The Catholic chaplain will be here then … G-6, the Captain told me that he found your area not policed up well enough this morning. Next time that happens passes for you will be stopped for four days … Are there any questions? … Now don't all try to talk at once …" He goes on with his instructions in the same gruff tone, relaxing only when the receiver has been replaced.

"Good lads they are," he says. "They know they've been assigned an important job and they're doing it well. They're not romantic kids with a glamorized view of this war. They're first-class ack-ack men who have come through a lot of rugged training with flying colors and they now want to use their technical knowledge and skill with their guns against enemy planes. I wouldn't give two cents for the safety of any Junkers or Messerschmits pilot foolish enough to fly into their 'field of fire.' I'm tellin' you those kids are good."

To see the crews scamper out to get into operating positions when the alert is sounded is to believe the lightning speed with which it is done. It sometimes takes one battery a little more than 60 seconds to have all its guns manned and at the ready, though during a recent alert one of the batteries was ready to have all of its guns firing 25 seconds after it had been notified of the approach of enemy planes.

Seldom does an alert come that most of the gunners don't hope that Jerry is really overhead and within range of the Bofors guns.

They are aching for opportunities to put to positive use what they have learned. Like most American Gl's they are anxious to go home as soon as possible but realize that they cannot do this while Hitler's Fortress stands unreduced and his now greatly diminished Luftwaffe possesses any degree of effectiveness.

During a recent alert two members of a gun section situated inside a village were winding up their weekly day off consuming mild and bitter in a pub 300 yards away from their gun. When the alarm was sounded these two, Pvt. Roosevelt Hawkins, a loader and firer from Chicago, Ill., and Pvt. Cornelius Jones, vertical gun pointer, of Chicago, forgot their bitter and ignoring the fact that they were off duty sprinted for their gun pit and went to their usual posts hoping to get a shot at a Jerry plane.

And throughout the battalion can be sensed this grim eagerness characteristic of finely trained troops waiting for combat action.

“A typical chow table at a battery mess hall,” read the original caption on this image, first published in the Northern Ireland edition of Stars and Stripes Feb. 10, 1944. A group of soldiers belonging to an all-Black anti-aircraft battalion stationed on the British Isles eat and socialize in their mess hall. (M.D. Weathers/Stars and Stripes)

One of those who wait is Cpl. Joseph Edmondson, Cleveland, Ohio, a gunner. Sometimes he sits on the embankment of the gun emplacement and listens to people entering the theater and two pubs that are almost under the barrel of his 40mm. gun. When he tires of this he will invariably go into his hut and start drawing figures of the beautiful women he has seen and known. It has become fashionable to describe Edmondson’s productions as “soldier art” — as apt a description as can be found for it. It is not obscene. His nudes have some of the earthiness of Gauguin’s South Sea beauties, though they will never fetch the Frenchman’s prices. There are other scenes that have their locales in the beauty spots of Cuyahoga County, the bustling life on pre-war Quincy Avenue and rhythmic music -making by the Pilgrim Four Quartet that used to be the Sunday Morning pride of WTIK. Edmondson has put these precious pictures into a large loose-leaf note book and some on wood. They have meaning for every man in his gun crew, reflecting many of their moods and urges, and these men have solid respect for the artist in their midst. Edmondson once boxed in amateur tournaments around Cleveland and can often be seen shadow-boxing within the shadow of his gun’s range-finder. He was a good light heavy. He is a good gunner.

Sgt. Gilbert Monroe, gun section chief from New Orleans, La., says that his men have improved in their ability to recognize plane types to a degree that makes him marvel at their keenness for the for the work.

These men now recognize most American and British aircraft by motor sound as well as by appearance,” he says. “They have acquired this ability over here.”

Monroe handles his crew like a mother, calls them his “babies,” and boasts that they can change barrels in faster time than any other AA gun crew in this theater. At general artillery drill he claims they are second to none.

The battalion’s batteries are spread over a dozen counties and their work is coordinated by Battalion Headquarters, which also functions as supply and ammunition distributing center.

Observer-spotters can be seen patrolling their gun positions night and day in damp valleys and bleak cliff sites. These men constitute the forward echelon of an organization presently charged with a mission of high strategic importance but which knows that the greatest task still lies ahead.

Want to find out more about Allan Morrison? Read Nancy Montgomery’s 2017 profile here.

Read more of Allan Morrison’s WWII reporting for Stars and Stripes by subscribing to Stars and Stripes’ historic newspaper archive. We have digitized our 1948-1999 European and Pacific editions, as well as several of our WWII editions and made them available online through https://starsandstripes.newspaperarchive.com/