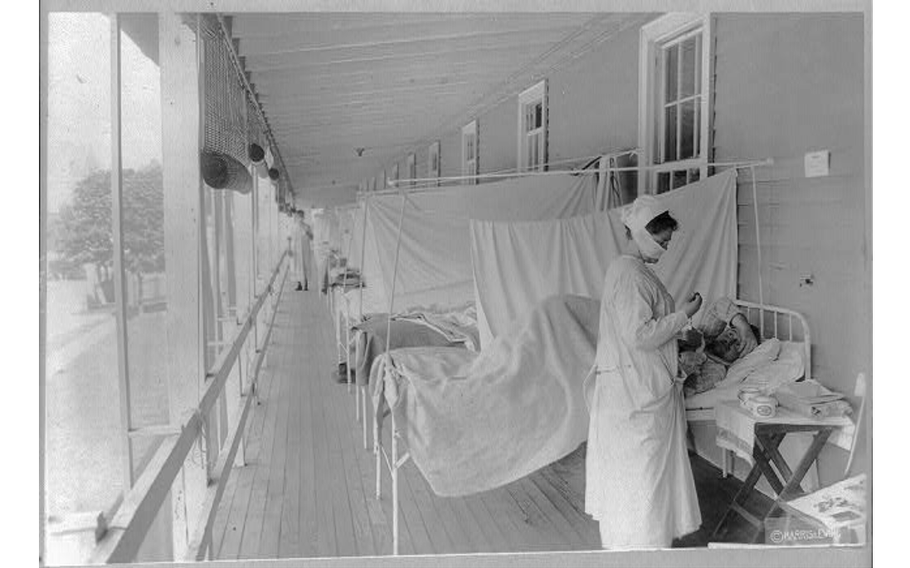

A nurse takes a patient’s pulse in the influenza ward at Walter Reed Hospital, Washington, D.C. , 1918 or 1919. (Library of Congress)

In 1920, Sen. Warren G. Harding campaigned for president on one of the blandest platforms in U.S. history. He promised neither hope nor change, nor making America great again. Instead, his slogan — which would help him win an unprecedented 60 percent of the popular vote — was a "return to normalcy."

"America's present need is not heroics but healing; not nostrums but normalcy; not revolution but restoration; not agitation but adjustment; not surgery but serenity," he told Americans in a speech four months before his victory.

After the two crises of World War I and the 1918 influenza pandemic, normalcy was a welcome salve. With 675,000 Americans dead of the flu — of at least 50 million victims worldwide — fear, anxiety and a residual national trauma permeated daily life. But many of the changes the virus had brought, for better and for worse, would not soon be reversed. (And ironically, Harding's presidential tenure would be defined not by normalcy but by scandal.)

Of course, other factors contributed to the societal upheaval of the 1920s — the war, long-simmering political tensions and immigration all played a role — but the fallout from the pandemic would transform the way that Americans lived, worked and learned.

Pandemics punctuate history, creating a schism between how life was before and how it might look in the future. As the United States emerges, haltingly, from the devastation of COVID-19, it's instructive to look back a century at how the country's last mass pandemic altered the nation's fabric — sometimes permanently.

Much as we're seeing now, with many Americans emboldened by coronavirus vaccines and feeling that the worst is behind us, the months and years immediately following the 1918 flu pandemic were marked by a desire to go out: to newly reopened cinemas, restaurants and family gatherings. There was even an uptick in Christmas shopping in 1918. The country was on the cusp of the Roaring '20s, a time of pushing societal boundaries and experimenting with new ideas.

Lurking behind the era's glitzy flappers and Wall Street speculators was a collective trauma of both the war and the pandemic. Dying of an infectious disease such as cholera or tuberculosis may have been a far more common experience then than that it is now, but the scale of mortality during the flu pandemic was extraordinary. Ten times as many Americans died of the 1918 flu as from the First World War.

"I think a lot of average Americans were traumatized by the flu," said Nancy Tomes, a historian at Stony Brook University specializing in popular understanding of disease. "The fact that this was such a common experience to die suddenly from an infectious disease makes you more stoical, but it doesn't rid the experience of the terror. And you deal with that in all kinds of weird ways."

One of those ways was a heightened fear of germs: Tomes said this pandemic may have spawned germaphobia. There was an urgent push to educate the public, including children, about the invisible threat of germs. Health curriculums arrived in public schools in the 1920s, including the "handkerchief drill," in which children as young as kindergarten students were taught to sneeze into their handkerchiefs with "military-style precision."

Even advertisements capitalized on fear of the flu to sell their products. "Don't let influenza get the upper hand!" warned an ad for Listerine mouthwash. The ad continued, "Never make the mistake of underestimating the menace of a cold, sore throat or Influenza. They may develop into serious or fatal conditions. You can probably recall such a case among your friends."

The public's understanding of infectious disease, set in motion by the public health crusaders fighting tuberculosis in the early-20th century, saw a groundswell shift following the flu pandemic. Well into the 20th century, germ theory had not yet taken hold among the broader public, and many Americans still believed that unhealthy vapors produced in dirty places caused disease. With the flu pandemic — and its ability to kill in country and in city, in dirty tenement and in clean estate — the public became convinced that disease passed from person to person. As Tomes put it: "Flu dealt the miasma theory a death blow."

The country succeeded in applying some lessons from the 1918 flu to another, less virulent one 10 years later. Colleges and universities, for instance, acted quickly to enact isolation techniques learned in the 1918 pandemic to limit the 1928 virus's spread.

At the same time, the high levels of flu mortality in 1918 caused a deep mistrust of traditional science. "There was a definite feeling that science had failed us," said Laura Spinney, science journalist and author of "Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How It Changed the World." As a result, the country saw a surge in both alternative medicine and anti-science groups. Christian Scientists, who generally reject medical care, saw their numbers boom post-pandemic, Spinney writes in her book. In the 1920s, one-third of the population of many U.S. cities visited alternative medicine practitioners in addition to traditional doctors, according to Spinney.

Racist pseudoscience such as eugenics also flourished in the post-pandemic years, fueled by anti-immigrant sentiment. "Xenophobia goes hand in hand with pandemics [since] the beginning of time," said Spinney, adding, "There's definitely this pervasive idea that if there was illness in the ghettos, in the poorest and most insalubrious parts of town, that was because those people were conditionally inferior — nothing to do with their environments."

Tomes said a desire to get away from people who were "stereotyped as being disease-carriers" contributed to a wave of suburbanization in the 1920s. Many young families also moved to the suburbs in the 1920s and 1930s to accommodate a baby boom that followed the war and the pandemic. (Even countries that had remained neutral during the war, such as Norway, saw a spike in birthrates.)

The flu also helped bring women into the workforce. Working-age men were in short supply: Many who hadn't died on the battlefield succumbed to the virus, which affected 20- to 40-year-olds disproportionately. Desperate for workers, industries that once barred women now accepted them into their ranks.

Women began working in fields once thought too dangerous or unfeminine: manufacturing, textiles, even science and medicine. Clinical diagnostic laboratory testing, for instance, became female-dominated, according to Lindsey Clark, an assistant professor in the laboratory sciences department at the University of Arkansas and author of a paper on how the pandemic changed women's lives.

By 1920, women were approximately 20 percent of employed people in the United States.

Suffragists, barred from holding rallies during the pandemic lockdowns, went door-to-door to campaign for their cause. Women's right to vote would be won in 1920, just months after the final waves of the pandemic blew through major cities.

"The war and the pandemic together gave women the opportunity to step up and prove that they are strong, and that they can be independent, and that they can take on those roles that previously they were thought to be too fragile to take on," said Clark.

The coronavirus pandemic has had the opposite effect on women's employment: A 2020 survey found that as many as 2 million women — disproportionately Black women — were considering leaving the workforce. Care work, whether for children or elderly parents, overwhelmingly falls to women, and the gender pay gap has pushed many women to opt to stay home rather than pay for expensive child care.

Much like the 1918 pandemic heightened existing bigotry against immigrants, this one seems poised to further entrench inequalities of both ethnicity and gender. And if the varied aftermath of the 1918 flu pandemic can teach us anything, it's this: The ravages of a pandemic only bring simmering societal issues to a boil, underscoring the prejudices that already exist. It will probably take decades for the true outcome to be known.

Jess McHugh is an author and journalist. Her book "Americanon," a history of U.S. bestsellers, was published in 2021.