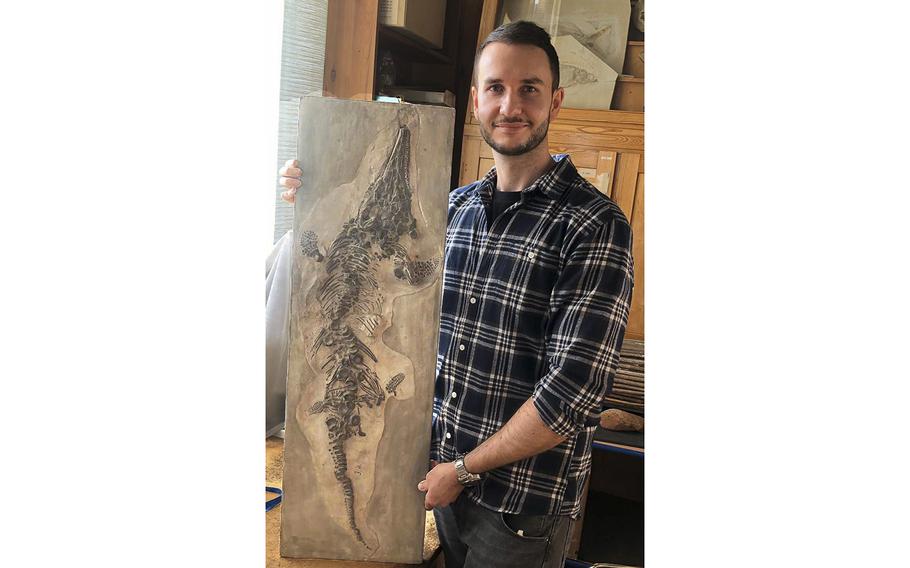

Palaeontologist Dean Lomax holds up a cast of an ichthyosaur. (Facebook)

In 1819, the complete fossil of an ichthyosaur dazzled scientists and the public. Thought to have been collected by pioneering English paleontologist Mary Anning, the fossil fanned interest in massive creatures that roamed Earth and swam the oceans millions of years ago.

But when a Nazi bomb obliterated the collections of a London museum during World War II, the fossil was lost to science.

Not anymore: Researchers recently uncovered two previously unknown casts of the famous fossil more than 75 years after the original's destruction.

They describe the rediscovery in Royal Society Open Science. It's a tale of historic hide-and-seek and a specimen with some serious scientific pedigree. In the early 19th century, ichthyosaur fever helped establish the field of paleontology and sparked public interest in fossils.

Anning, a fossil hunter and paleontologist who was excluded from full participation in the scientific community because of her sex, is thought to have found the specimen in Lyme Regis, England, at some point before 1818. She lent it to British surgeon Everard Home, who included it in some of the earliest research on ichthyosaurs. The groundbreaking fossil - the first complete skeleton of its kind ever recognized and documented by scientists - eventually made its way to the Royal College of Surgeons in London.

During the Blitz of 1941 in London, the fossil was obliterated by a German bomb. No copies were known to exist. But while conducting research on other fossils at Yale University's Peabody Museum of Natural History in Connecticut, a pair of paleontologists found a plaster cast painted to resemble a fossil. They recognized the impression as a copy of the original ichthyosaur fossil and eventually tracked down another in Berlin's Museum of Natural History Berlin. Neither had been properly labeled.

Scientists still study ichthyosaurs, marine reptiles that swam in oceans between about 250 million and 90 million years ago. But more information may be hiding in plain sight in museum collections, the researchers suggest.

"This discovery demonstrates the necessity to carefully preserve undetermined and casted material in a natural history collection," Daniela Schwarz, the scientific head of the Museum of Natural History Berlin's fossil reptiles department, said in a statement. "There will always be someone who discovers its scientific value in the end."