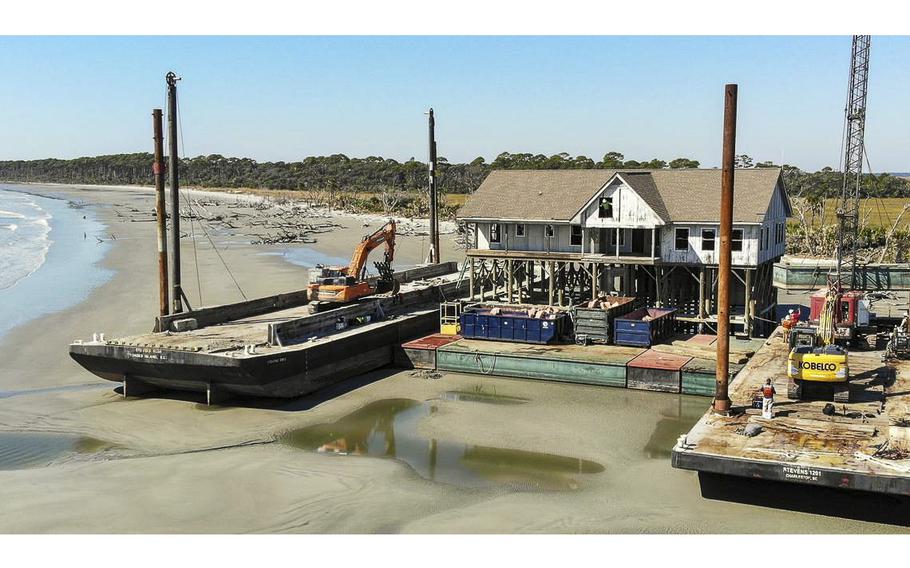

A worker looks out of an access cut into the gabled roof of USCB’s former maritime laboratory as work begins to remove the structure on Monday, Oct. 24, 2022 on Pritchards Island, South Carolina. (Drew Martin)

On a day brisk enough for slacks and bright enough for a bucket hat, Philip Rhodes wore both while casting his line into the Atlantic.

Like any fisherman, he watched patiently from the comfort of a plastic chair while waiting for a bite. Like any fisherman, as he waited, he shot the breeze with longtime friends, sharing stories as vast and unbridled as the sea in front of them.

But really Rhodes wasn’t any fisherman — not when he was here on his beloved Pritchards Island.

Unassuming, with kind eyes and a competing wit, the businessman was a quiet legend on the Beaufort County barrier island he owned.

The rugged 1,600-acre expanse, near-barren of development, and teeming with Lowcountry flora and fauna was Philip Rhodes’ “happy place,” said his son Steve. And Philip was happy to share it — at first with friends and family, and then with the University of South Carolina.

From the moment he deeded the island to the university, Rhodes worked to protect it.

He ensured it was kept from vast development. Instead, he wanted it to be used as a place to learn and enjoy in the same way he did. He fully funded the construction of a stilted lab building that became symbolic to all who knew the island. And for years, Rhodes made substantial financial contributions to help USC-Beaufort keep Pritchards’ operations afloat.

Now, nearly 13 years since his death, his happy place is one he may no longer recognize.

Erosion has whittled away hundreds of yards of dunes. Dried up funding left the island unused by USC for over a decade. The lab building, once set back among palmetto trees and live oaks that now sit in water at high tide, is now gone.

What made Rhodes’ legacy on Pritchards is all but wiped away today. However, after recent pressure from his family and a promise from Gov. Henry McMaster, USC is fighting for the island’s revival in the way Rhodes intended.

A chapter is closing on Pritchards “but it’s not the end of it,” said Joe Staton, a department chair at USCB.

This is Philip Rhodes’ chapter.

Purchasing Pritchards

A call came through in 1979 by way of Rhodes’ lawyer: An island had been put up on Beaufort County’s auction block.

Pritchards had been seized from its owner, former Georgia Sen. Eugene Holley, in a lawsuit over unpaid mortgages.

Holley had big plans for the island before then, proposing to dot it with beige toadstool houses. Just two mock-ups stood after Rhodes outbid media mogul Ted Turner and nabbed Pritchards for $1.275 million that year.

But Rhodes wasn’t interested in development. Far from it.

An Atlanta native, he became acquainted with the Lowcountry’s lush landscape in the mid-1930s while training at Parris Island Marine Corps Recruit Depot. In late 1944, as a quartermaster stationed in Leyte, an island in the Philippines, he awed at the Southeast Asian country’s untamed thick vegetation and rampant wildlife.

Over 30 years after his stint as a quartermaster and then-president of S.P. Richards, Rhodes fell in love with another island. He and his son Steve headed to Georgia’s southernmost barrier island for a getaway.

The two walked miles of Cumberland Island’s sprawling beach with characteristically tall dunes that shared Pritchards unfettered nature. It was a place his father “fell in love with,” Steve remembered.

But shortly after the trip, Philip Rhodes fell in love all over again with another barrier island nearly three hours north of Cumberland.

And this time, it would become his.

From quartermaster to island owner

Though Rhodes loved the island, there wasn’t much that was easy about spending a day on Pritchards.

No running water. No electricity. No helping hands. And getting there required a boat, swimming endurance, or patience for a tide low enough to walk a sometimes-visible sandbar between Fripp Island and Pritchards.

The challenges weren’t unnerving to Rhodes. For the life he lived, they may have been ordinary.

He’d grown up during the Great Depression as a teenager in Atlanta. When he married Edith in 1941 at 25 years old, they could only afford a garage apartment on his wages as a newly-minted manager at S.P. Richards Paper Co. in Montgomery, Alabama. A year later, the Marine Corps whisked him away to Norfolk, Virginia, where he bought 1,000 feet of wire and hooked up electricity to his home after he spent two weeks without lights and hot water.

After three years as a quartermaster, upending life to report to where he was needed, Rhodes, Edith and their two boys settled into a new home in Atlanta that was heated by a single pot-bellied stove during the chilly months.

The same logistical skills he showed as a quartermaster, scoutmaster and young husband served him well when he became Pritchards Island’s owner decades later.

An orange juice can brimming with bleach would sterilize a giant tank of collected rainwater, his eldest grandchild, Martha Rhodes, recalled of their time on the Beaufort County island. The two would lug over drinking water from Fripp during their trips. Sorghum jars were doorstops. He drank his evening cocktail from a recycled jelly jar that read “prune juice” as he walked the beach.

On one trip to Pritchards, she learned from her grandfather to embrace a challenge.

With a stubborn fish tugging at her line, Martha followed it half a mile across Pritchards’ 2.5-mile shoreline. She watched as her grandfather worked his way toward her, grasping a small Igloo cooler. It wasn’t the relief she’d hoped for.

He pulled out a Coke, popped the top and handed it to her.

“It’s your fish, and you’re going to get it,” he said and walked away with more belief in his granddaughter than she had in herself.

For about two decades, the Rhodes family fished and swam Pritchards’ waters, cooked from the island’s designated recipe book and, to honor the patriarch’s favorite pastime, navigated a tractor along a clearing cleaved through the center of the maritime forest.

They’re memories that don’t feel so far away as Martha, long grown from the little girl who reeled in her own stubborn fish, recently reminisced while poring over black and white photographs of her grandfather in her Charleston home.

In them, he’s sitting on the tractor, likely having rumbled along the island’s rippled sand, with his gaze pitched to the Atlantic. They’re time capsules she treasures differently from a stack of photographs and documents.

As her father, Steve, recounted another memory, she quietly rose from her seat to return the frames to their rightful place – outside her bedroom door, just a few feet across from a painting of Pritchards Island.

Her grandfather and caring for the island never out of her sight.

Pritchards’ kindred spirits

Before rapid erosion chewed at Pritchards’ shoreline, Rhodes could drive his red Chevrolet – tugging along a rig he built to haul fishing equipment – from the north end to the south end.

Forty years ago, the toadstool houses and two rickety fish camps still stood. Decades ago, it was safe to land a plane on the island.

These were truths that Rhodes and his handful of fishing buddies knew.

Their days were mostly spent fishing, of course, while the evenings featured Rhodes as the chief cook. But other times, even into their 70s, the crew would scale ladders to clean and empty one of the toadstool homes or spend time following a fawn they named “Honey.”

One of those men, who in his 2018 obituary was called “Mr. Boys & Girls Club,” was a staple in the group: Joe Mix.

It’s a bit of a mystery how Mix and Rhodes became fishing buddies.

Mix’s daughter, Amy Mix Poggi, suspected it happened during a routine breakfast that was held in downtown Beaufort. Regardless of circumstance, the men, without familial ties to Beaufort, shared an undying love for the community.

“They were very much kindred spirits,” Mix Poggi said. “Dad was always talking about Philip Rhodes.”

Without Rhodes’ lifelong devotion to southeastern Boys & Girls Clubs, Mix probably wouldn’t have entered into the sphere, his daughter added. It was a cause that the two “put their hearts and souls into,” said former Beaufort Mayor Billy Keyserling.

Handing the island to USC

As the story goes, Rhodes donated half the island to USC in 1983, then, except for a small slip with a home tucked away in the woods, he gave the remaining half to the university nearly six years later.

Deeds signed by him and the then- Carolina Research and Development Foundation required USC to keep Pritchards Island in a wilderness state and to use it for scientific, educational, charitable and general public purposes.

Rhodes’ donation was a “blending of genuine benevolence and an already deep love for the island with pragmatism,” his son said.

But David McCollum, a beloved USC-Beaufort professor, was the driving force in what happened next – an integral turning point in Pritchards’ history.

“David talked about Philip Rhodes a lot,” said Betty Lorick, the late McCollum’s ex-wife. “And apparently Mr. Rhodes really liked the work David was doing.”

In fact, Rhodes was so taken by McCollum’s loggerhead sea turtle research on the island that he donated $300,000 to have a lab fully constructed — the remaining funds spilling into operating costs — to promote further research and education.

By 1992, at the time of the lab’s dedication, then-island director McCollum said it would make research life “a whole lot easier” and Rhodes sang the praises of McCollum and USC under the pristine 3,500 square-foot building on stilts.

But there was a slight problem that day for the man who compulsively labeled everything — from mason jars to a stapler with his “Philip A. Rhodes” printed four times over. He wanted his philanthropy kept quiet.

His name was plastered on a sign in large bold letters that hung from the lab, but shortly after it went up, he brought it down and tucked it away. It was a small gesture that said so much about who Rhodes was.

He just wanted everyone to love Pritchards the way he did. And for about 15 years, they did.

Researchers, professors, students and community members took to the island to study and learn about loggerhead sea turtles, tides, shorebirds, barrier island dynamics and salt marsh ecology. Some stayed in the lab and others took day trips. Artists came and went. Yogis practiced on the beach.

For about six years, beginning in 1999, Amber Von Harten and her husband managed Pritchards Island, ran programs on it and conducted research. When the Von Hartens ran into Rhodes, they had good conversations about fishing, conservation and research.

Like so many had said before her, she remembered Rhodes was “always a kind and generous man.”

For years, Rhodes wrote a hefty check to fuel operational costs. The Turner Foundation also funneled thousands in funding into Pritchards. Over time, the South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control ponied up money for Pritchards, and so did several other private donors and numerous community members. Overnighters, who paid to stay in the lab, also contributed.

That money went to program costs, manager salaries, boats, a docking fee at Fripp, and maintenance and utilities.

But by the early 2000s, the island was rapidly eroding and so was private and state funding. The final stretch was in 2007 when USC was part of a multi-million federal program to measure ocean currents and waves using a radar system. Two years later, the same year Philip Rhodes died, the once lively Pritchards went quiet.

The money had dwindled and the lab had deteriorated.

For the latter 13 years, the unused peeling lab building stood as a relic, rousing curiosity and an emblem of the island’s once-zenith to those who knew it.

A new chapter

“Have you heard the story about Phil Rhodes when he saw Pritchards after he bought it?” longtime Fripp residents ask.

They joke that he purchased the island when he saw it at low tide, enamored with its expanse. But when he came back and stared at Pritchards at high tide, while standing on Fripp’s shore, he quipped, “What happened to my island?”

That was 43 years ago. That was hundreds of yards or dunes ago. That was millions of dollars ago.

Development and shore stabilization efforts on Fripp have squeezed Pritchards even narrower and faster than expected of barrier islands. And Rhodes likely would be dismayed about the University of South Carolina’s neglect of Pritchards.

He thought he’d set the groundwork for Pritchards Island’s future in the 1980s when the deeds contained a clause that said USC could lose control of the island to the University of Georgia or The Nature Conservancy if it didn’t uphold its end of the bargain.

Earlier this year, his family spoke out about their disappointment over the island’s disuse. That triggered a promise from Gov. McMaster to keep Pritchards in USC’s hands, and the Beaufort campus has quickly developed preliminary plans and a budget for a renaissance. About $1.25 million in Year One start-up costs stand in the way.

Rhodes’ family says the plans give them hope. Unfortunately, saving the lab wasn’t possible.

On Monday, a handful of Fripp residents walked to the edge of Skull Inlet to watch the slow-moving commotion on Pritchards.

Two cranes, sitting atop a barge, loomed over the dilapidated lab. One resident called its demolition bittersweet. Another said she was depressed to see the building come down.

Perhaps the removal symbolically ends the most recent chapter of Pritchards Island’s life — one of neglect. There’s hope that the new chapter will fulfill Rhodes’ dream for the island he loved, the island that is still his home.

In 2010, shortly after Rhodes’ chapter ended, those who loved him dearly gathered on the island on a blustery gray day to fulfill his last wish. He’d written in a 2003 account of his life that he wanted his “ashes to be scattered on the beach at Pritchards Island.”

Philip Rhodes never left his happy place.

©2022 The Charlotte Observer.

Visit charlotteobserver.com.

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.