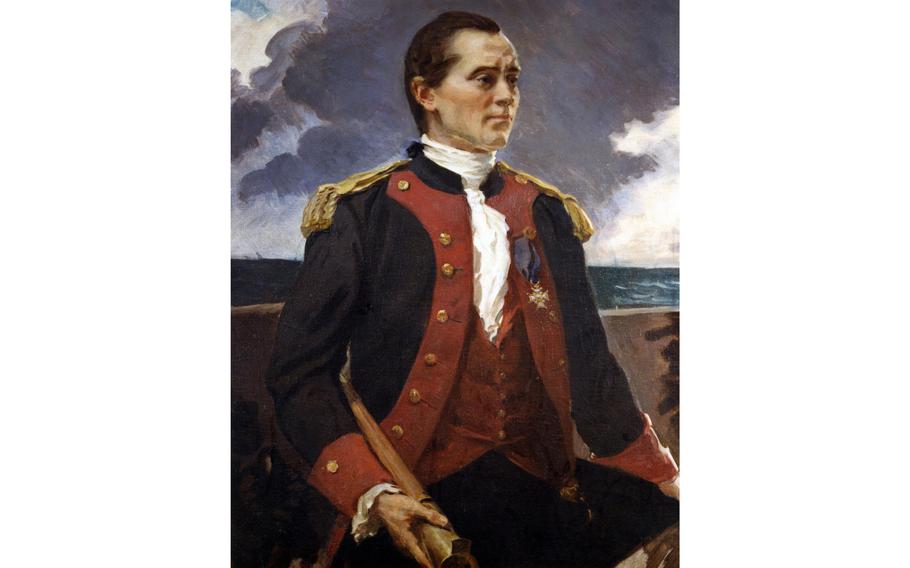

The man some call the “Father of the American Navy,” Capt. John Paul Jones, cashed in on his service and fame as a war hero to command a Russian warship for Catherine the Great. (U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command)

American officers have parlayed their military experience into financial gains from foreign governments since the Revolution. Even the man some call the "Father of the American Navy," Capt. John Paul Jones, cashed in on his service and fame as a war hero to command a Russian warship for Catherine the Great.

Jones, a native of Scotland, arrived in Fredericksburg, Va., in 1774 and was soon appointed to the Continental Navy. During the Revolutionary War, he commanded ships off the Atlantic coast, in the Caribbean and in European seas, capturing and destroying more than a dozen British vessels.

The war made Jones aware of "emoluments," defined at the time to include bounties or money paid for naval victories. In an Oct. 17, 1776, letter to Robert Morris, a member of the Second Continental Congress' Marine Committee, Jones listed 16 ships he had captured or destroyed and bemoaned the "paltry emolument[s]" paid by the Continental Navy.

He warned that Britain and other foreign powers paid more and that there was a "necessity of making the emoluments of our navy equal, if not superiour, to theirs," or else lose the best men.

The framers of the Constitution shared his concern that foreign payments could harm American interests. In Federalist Paper 22, Alexander Hamilton warned: "One of the weak sides of republics … is that they afford too easy an inlet to foreign corruption."

Some of the framers had received lavish gifts from foreign states. When Benjamin Franklin departed as minister to France, King Louis XVI presented him with a snuffbox encrusted with 408 diamonds and inset with the king's portrait. Thomas Jefferson and two other ministers to France were also given snuffboxes. The king of Spain, Charles III, presented Minister John Jay with a horse.

To combat potential bribes, the framers in 1787 adopted — with almost no debate — language based on the 1781 Articles of Confederation that prohibited all persons "holding any Office of Profit or Trust" from accepting any "present, Emolument, Office, or Title, of any kind" from any "foreign State" without approval from Congress. This provision is now known as the foreign emoluments clause.

As Edmund Randolph, Virginia's governor and a delegate to the Constitutional Convention, said at the time: "This restriction is provided to prevent corruption."

The foreign emoluments clause has remained unchanged for more than 230 years, but for one key adjustment: In 1977, Congress delegated its authority to approve foreign work by retired military personnel to the secretary of their military service and the secretary of state.

In June 2017, the state of Maryland and the District of Columbia sued President Donald Trump for violating the foreign emoluments clause by profiting on payments from foreign leaders to his D.C. hotel. Trump appealed to the Supreme Court, which eventually held that the case was moot because he was no longer in office.

At the height of the Revolutionary War, Jones sought approval from Congress to sail on a French ship to attack the British in Jamaica. The Continental Congress approved, though James Madison argued against it. In the end, the colonies defeated Britain before Jones and the French fleet saw battle.

After the war, the Continental Navy was disbanded, and Jones, in his late 30s, found himself without a ship to command. Despite the American prohibition against receiving emoluments from a foreign power, Jones decided to take advantage of the fact that foreign governments wanted to reward him.

In 1788, Jones was offered a command in the Russian navy by Catherine the Great, who sought his expertise to battle the Ottoman Empire in the Black Sea. Jones accepted the offer and went to work as a rear admiral commanding the 24-gun flagship Vladimir.

Jones later wrote Jefferson, then minister to France, that despite the job, he had not "forsaken" America. He wrote: "I can never renounce the glorious Title of a Citizen of the United States!"

He admitted that he had not secured "explicit approval" from Congress to work for the Russian navy. But he argued that the Continental Congress's 1782 approval for him to serve in the French navy should also apply to his service in Russia, because both jobs "facilitate my improvement in the Art of conducting Fleet and Military Operations."

Because the United States had no navy, there was "no public employment for my Military talents" and "no emolument or profit whatever" from the military, Jones said. He asked Jefferson to smooth things over with Congress.

Despite the constitutional prohibition, Jefferson endorsed the idea. He wrote to a friend that Jones was "young enough to see the day" when an American navy could fight the British "ship to ship," and that "we should procure him then every possible opportunity of acquiring experience."

Jones' command of the Vladimir helped the Russian navy defeat the Ottomans in a key battle in 1788 and secure control of the Crimean Peninsula.

Despite the victory, Jones — disliked and discredited by fellow officers in the fleet — was recalled to St. Petersburg. There he was accused of raping and beating a 10-year-old girl. A campaign in the Russian court led by the French ambassador saved Jones from standing trial. However, Catherine the Great effectively banished Jones from Russia for his actions and he fled to Paris in international disgrace.

Jones lived his final years in France, surviving on his Russian pension. He died on July 18, 1792, and was buried in what would become an unmarked grave. The "Father of the American Navy" was largely forgotten until 1905 when the U.S. ambassador to France had his body exhumed and returned to the United States.

Jones' remains were interred at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis. President Theodore Roosevelt eulogized Jones as a man whom "every officer in our Navy should feel in each fiber of his being an eager desire to emulate." The president made no mention of Jones' time in the Russian navy.

Jones rests in an ornate marble tomb in the academy chapel. The tomb lists each of the ships he commanded in war, with one exception — the Vladimir.