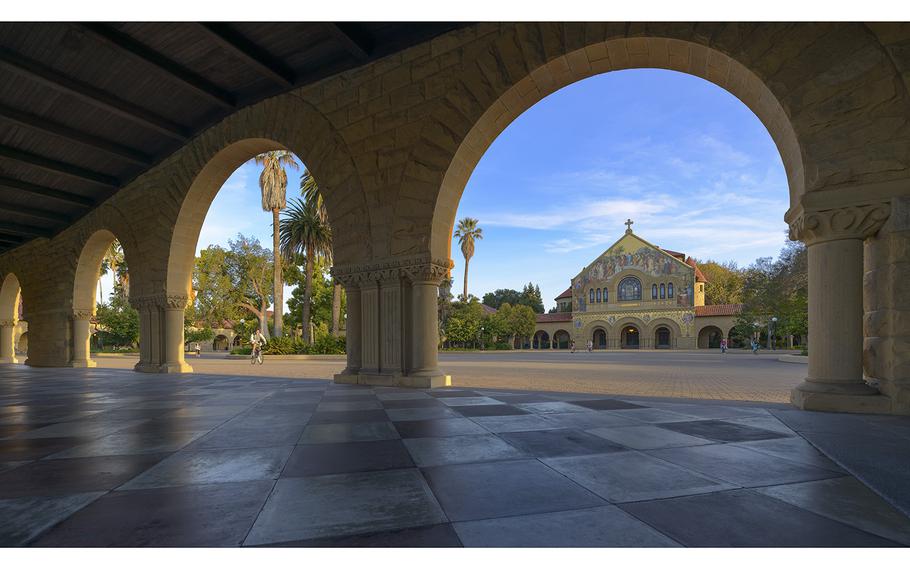

Arches at Stanford University frame the Memorial Church in the background. (WikiMedia commons)

Stanford University apologized on Wednesday after an internal task force confirmed the school had limited the admission of Jewish students during the 1950s and then "regularly misled" those who inquired about it afterward.

The university's president, Marc Tessier-Lavigne, called the restrictions "appalling anti-Semitic activity," in a university-wide note, adding that "this ugly component of Stanford's history, confirmed by this new report, is saddening and deeply troubling."

The practices were first reported on a blog by historian Charles Petersen, who wrote last year in a post titled "How I Discovered Stanford's Jewish Quota" that a memo in the school's archives amounted to "a historical smoking gun."

Petersen found a 1953 letter to J.E. Wallace Sterling, then the president of Stanford, from the assistant of the admissions director, Rixford Snyder, in which it was noted that the incoming freshman class would have a "high percentage of Jewish boys." Snyder, the assistant wrote, "thought that you should know about this problem, since it has very touchy implications."

The memo lamented that "the University of Virginia has become largely a Jewish institution, and that Cornell also has a very heavy Jewish enrollment." It warned that if Stanford were to accept "a few" applicants from two heavily Jewish high schools in Los Angeles, "the following year we get a flood of Jewish applications."

Such a dilemma, the memo said, forced them to "disregard our stated policy of paying no attention to the race or religion of applicants."

The report by the task force - which was assembled nearly a year ago - found in its review of annual reports from the registrar's office that from 1949 to 1952, Stanford enrolled 87 students from the two schools, Beverly Hills High School and Fairfax High School. From 1952 to 1955, however, only 14 students were enrolled from those schools. The report said that records "do not indicate any other public schools that experienced such a sharp drop in student enrollments over that same six-year period or any other six-year period during the 1950s and 1960s."

Tessier-Lavigne, the current president, said the practices - as well as "the university's denials of those actions in the period that followed" - were "wrong," "damaging" and "unacknowledged for too long."

Arguments in a case over modern-day quotas at an elite institution are set to be heard at the Supreme Court this month. A group of Asian Americans is suing Harvard - which also limited its admissions of Jewish students early in the 20th century - alleging that the university unfairly discriminated against them by capping admissions as a sort of "racial balancing" of its students. Harvard denies the allegations. The plaintiffs have cited Harvard's past quotas on Jewish students as evidence in their case.

Petersen, the historian, had written that the only previous comment he could find from the admissions office on the topic was a statement in 1996 to the Stanford Daily, the school newspaper, in which an admissions official said such allegations were simply "rumors" and that "assertions of the existence of quotas are only based on the convictions of the few Jewish members of the Stanford community in the '40s and '50s."

"Either the admissions office was lying," Petersen wrote, "or else they didn't look that hard."

Rabbi Jessica Kirschner, executive director of Hillel at Stanford, said in an email that "for the people who knew there was something wrong despite official denials, hearing the symbolic head of the university speak the truth out loud and apologize is validating, and maybe even healing."

She said the university's response Wednesday was "an example of what productive institutional apologies look like," noting how "a new generation of Stanford leadership took evidence seriously, commissioned a strong task force, and did not flinch when its findings did not reflect well on the institution."

Sophia Danielpour and Ashlee Kupor, co-presidents of the Jewish Student Association at Stanford, said in an email that while they were "disappointed" about this aspect of the university's history, they were "also appreciative that Stanford allowed a thorough discovery process and issued a real apology."

They said they hope the findings spur "concrete changes," including awareness of the Jewish high holidays in relation to the academic calendar and of a "blind spot" in the school's diversity and inclusion efforts "that doesn't always include religious minorities."

In his note to the school, Tessier-Lavigne wrote that Stanford will implement a number of recommendations from the task force, including addressing the "deeply regrettable" scheduling of the start of Stanford's fall quarter during Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish new year, which happened last month. Stanford will also create an ongoing Jewish advisory committee, he said.

Tessier-Lavigne added that "it would be natural to ask whether any of the historical anti-Jewish bias documented by the task force exists in our admissions process today. We are confident it does not."